Voices from the past, lessons for the present

The Palmetto State’s rich history of civil rights advocacy takes center stage in UofSC’s civil rights history center

Posted on: April 18, 2018; Updated on: April 18, 2018

By Chris Horn, chorn@sc.edu, 803-777-3687

Every photograph, no matter how commonplace, has a story to tell — sometimes a powerful one. Bobby Donaldson has learned that lesson time and again as an associate professor of history, and especially so as director of Center for Civil Rights History and Research.

It happened a few years ago when he visited the South Caroliniana Library and came across a black-and-white image of a group of African-Americans standing in line to vote. The cryptic label indicated only that it was taken in 1948.

“Then I met a woman who told me her mother was in that photograph and was still living at age 99,” says Donaldson, associate professor of history in the College of Arts and Sciences. It was 2008 and he arranged to interview the elderly woman right away; Donella Brown Wilson was now blind and had trouble hearing.

“I would pose a question and her daughter would repeat it loudly in her mother’s ear, and Mrs. Wilson, almost as if you pressed ‘play,’ would then reel off meticulous details of history. She had an astounding memory.”

Wilson talked about all that she had witnessed growing up in Calhoun County, South Carolina, and how hopeful she had been that change would ultimately come.

“She said to me, ‘That photograph was in 1948, the very same year Strom Thurmond ran as a Dixiecrat to challenge the integration of public spaces and the emerging civil rights movement,’ ” Donaldson recalls. “‘Every time we voted, we kept losing,’ she said, ‘every time, and yet we kept voting.’

“And now it was 2008 and she was preparing to vote yet again, this time for an African-American running for president of the United States.”

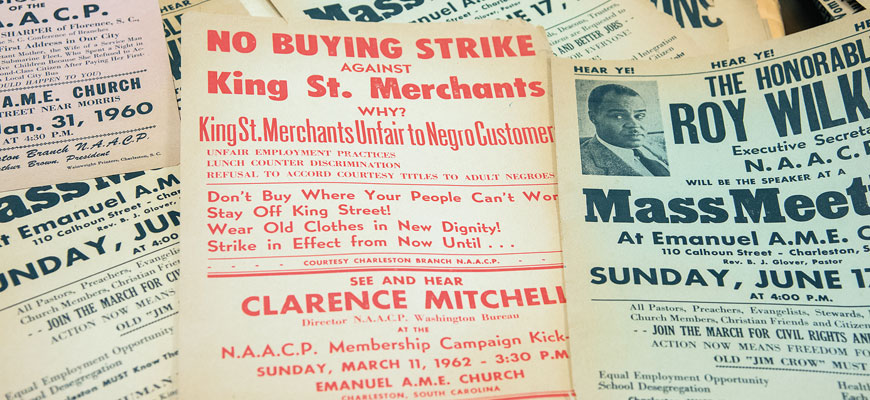

Donaldson’s oral history interview with Donella Brown Wilson is part of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research archive collection, which includes papers, historic documents and images from South Carolina’s civil rights past. Familiar names like photographer Cecil Williams and Modjeska Simkins, as well as unfamiliar ones who were nonetheless part of the civil rights movement, can be found in the archive.

The center, a joint project of University Libraries and the College of Arts and Sciences, was established in November 2015 with the receipt of the congressional papers of U.S. Rep. James E. Clyburn, the state’s first African-American member of Congress since Reconstruction. Clyburn was also a social studies teacher in the 1960s and a veteran of the civil rights movement.

Last year, the center developed a teacher training institute with a grant from the National Park Service. Fifteen middle- and high-school teachers from around the state came to campus to learn more about South Carolina’s rich history of civil rights through the center’s archives and speakers.

“We exposed them to the primary sources in our University Libraries, and we also invited civil rights veterans to share their experiences with the hope that the teachers would incorporate those insights into future lesson plans,” Donaldson says. The goal is to share those lessons with other teachers in South Carolina and across the country.

Students get really excited when they can see history up close, and it’s not simply what they’re reading in the textbook.

Bobby Donaldson, director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research

In addition to acquiring papers of other prominent civil rights and African-American figures, the center draws on the materials and staff expertise of South Caroliniana Library, Thomas Cooper Library, the Music Library, Ernest F. Hollings Special Collections Library, Moving Image Research Collections, Digital Collections and the Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.

“Not only do these archives and collections inform scholars and students, they also inform participants who have long forgotten some important details about their work and are quite surprised that what they did was recorded or might have historical or scholarly relevance for today,” Donaldson says, noting that conducting oral histories with aging civil rights activists is an important and ongoing work of the center.

“Students get really excited when they can see history up close, and it’s not simply what they’re reading in the textbook — it’s what they are hearing from oral interviews from people who were there,” Donaldson says. “If we do not fully educate students about this history and have them take this history forward, some of the invaluable details of the past may fade away.”

While the center focuses much of its efforts on illuminating the past, its work also offers context to current events such as National Anthem protests by NFL players and debate over historical monuments honoring individuals now viewed by many as racist.

“We remind students that current debates about kneeling and public protests are not new,” Donaldson says. “There are photographs in Orangeburg of African-American ministers in the city square in 1960, kneeling in prayer as they challenged racial injustice.”

Then there was the case in 1961 of more than 300 students, including a young James Clyburn, marching from Zion Baptist Church to a demonstration on the Statehouse grounds. After singing “We Shall Not Be Moved” and “The Star-Spangled Banner,” many of the students were arrested for breach of peace. Their criminal convictions were ultimately overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, a precedent ruling cited by lawyers in Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama.

“As part of the center's mission, we work to analyze and document how current social and political events are shaped by a historical context,” Donaldson says. “We also seek to train a young cohort of historians and teachers who will continue to preserve these incredibly important stories from the past.”

Share this Story! Let friends in your social network know what you are reading about