Our history of holding the powerful accountable for their wrongdoings

In 1778, before the Constitution had even been written, the Continental Congress passed the first whistleblower protection law in the world, cementing whistleblowing as a foundational aspect of the American experiment.

In 1775, Commodore Esek Hopkins of Rhode Island was named commander-in-chief of America’s first armed force at sea, the Continental Navy. From the beginning, Hopkins disregarded his orders from the Second Continental Congress. He was instructed to take his fleet south to clear the British from the Chesapeake Bay, but instead he sailed to the Caribbean, seizing cannons from a British outpost in Nassau. General George Washington asked Hopkins to coordinate the movement of the navy with that of the army, but Hopkins refused, leaving Washington to fight the British without naval support in both Boston and New York. Instead of engaging the enemy as ordered, Hopkins plundered British naval and merchant vessels. While plundering ships was at that time a legitimate means of augmenting the navy’s purse and paying the crewmen, more than his fair share went into Hopkins’ own pocket, while the Continental Navy’s sailors often went without pay. As a consequence, when new ships were added to the fleet, the navy couldn’t find men to crew them; sailors instead signed onto good-paying privateer vessels. For disregarding orders Hopkins was censured by Congress, but ultimately, he was returned to his command.

The breaking point for Hopkins’ men came in 1777, when the Commadore issued an order directly countermanding orders from Congress. Just days later, ten officers of the Warren, Hopkins’ ship, petitioned Congress to remove Hopkins from command. In addition to the indiscretions Congress already knew about, Hopkins’ men shed light on a self-serving commander with utter contempt for those in authority over him. Most alarmingly, testimony from multiple sources revealed Hopkins tortured British prisoners of war, violating Congress’ mandate that prisoners be treated humanely. Congress responded to the complaint by suspending Hopkins, pending investigation into the allegations. In January of 1778, after that investigation returned definitive proof of his wrongdoings, Hopkins was formally relieved of his command and dishonorably discharged from service.

That it is the duty of all persons in the service of the United States, as well as all other the inhabitants thereof, to give the earliest information to Congress or other proper authority of any misconduct, frauds or misdemeanors committed by any officers or persons in the service of these states, which may come to their knowledge.

The Second Continental Congress, July 30, 1778

As has happened to so many whistleblowers since, the men who spoke out against Hopkins faced retribution. Two of the ten men, Samuel Shaw and Richard Marven, lived in Rhode Island, where Hopkins’ prominent family held considerable sway. Hopkins exerted his influence to have Shaw and Marven arrested and jailed on charges of libel. The two once again approached Congress—this time for relief from Hopkins’ retaliatory measures.

Though the word “whistleblower” was not yet in use (the term’s modern usage came about in the twentieth century), the concept was clearly understood by our nation’s founders. In a show of solidarity with Shaw, Marven, and all who speak truth to power, on July 30, 1778 Congress declared: “That it is the duty of all persons in the service of the United States, as well as all other the inhabitants thereof, to give the earliest information to Congress or other proper authority of any misconduct, frauds or misdemeanors committed by any officers or persons in the service of these states, which may come to their knowledge.” Congress ordered the release of Shaw and Marven. Additionally, they passed a special resolution specifically to protect the two whistleblowers, so that “the reasonable expences of defending the said suit be defrayed by the United States.” Congress paid $1,418 for Marven and Shaw’s legal fees from the United States’ limited funds, equivalent to about $50,000 today. Additionally, all congressional records pertaining to Hopkins’ case were made public, thereby establishing a precedent of transparency in handling cases of corruption and fraud by public officials.

It is astonishing that, amid an arduous and costly revolution, Congress took measures to acknowledge the importance of whistleblowers and the role they play in preventing those in power from going unchecked. At that time in history, the idea that common people could report the wrongdoings of someone as powerful as the commander-in-chief of the navy and not only be heard, but also succeed in toppling him from his position, was a uniquely American phenomenon. While many other countries now have whistleblower laws on the books, the United States incorporated whistleblowing into its founding, demonstrating to the world the American ideal of equality in the eyes of the law. Though we often fall short of this standard, our nation’s first whistleblowers—and their supporters in Congress—set a powerful example for us to follow.

If you witness wrongdoing in the workplace, you can file an anonymous report via the university’s Integrity Line.

References

“Chapter One: ‘Truths.’” Whistleblowers: Honesty in America from Washington to Trump, by Allison Stanger, Yale University Press, 2021.

Grassley, Chuck. “Honoring America's Truth-Tellers.” Chuck Grassley: United States Senator for Iowa, 1 Aug. 2013, www.grassley.senate.gov/news/news-releases/honoring-americas-truth-tellers.

“Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Official Inflation Data, Alioth Finance, 26 Jun. 2021, https://www.officialdata.org/.

“Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789.” American Memory: Remaining Collections, Library of Congress. memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/.

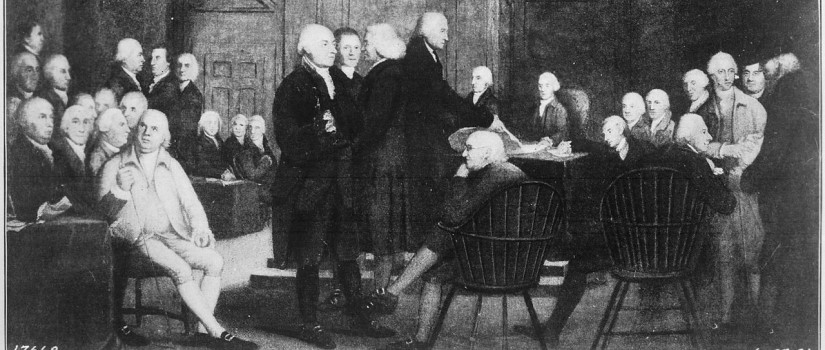

Banner Image: “The Second Continental Congress Voting Independence,” artist unknown. Courtesy of the National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/532839.

Callout Image: Engraving by John Chester Buttre. “Esek Hopkins of Rhode Island, Commander in Chief of the American Navy 1776.” 1778. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003675609/.