Authors

Kelsey Thomas, Wendy Chu, Melanie Palomares, Ph.D.

Psychology 228 (Laboratory in Psychology) is a capstone class for psychology majors and minors. The main goal of the course is the completion of an independent research project, which the student develops themselves from idea to data analysis over the course of the semester. The instructional team is led by faculty member Dr. Melanie Palomares and dedicated graduate students. The 2019-2020 graduate student team consisted of Wendy Chu, Kristin Kirchner, Samantha Langley, Jaleel McNeil, Jonathan Rann, and Daria Thompson.

Students were encouraged to develop a study based on their personal interests such as social media, interpersonal relationships, or exercise. Following certification in human subjects training, the students collected data by deploying surveys and assessments to their target demographic. Students analyzed and interpreted their data using SPSS, a statistical software. Students then wrote a full length, APA style research paper about their project. Students from this class acquired several skills such as responsible research conduct, survey creation, statistical software analysis, and professional writing. This class provided the opportunity for undergraduate students to preview the graduate student research experience. The students published here went the extra mile and prepared their research papers for this publication, which often included additional, more sophisticated data analysis and new research questions.

Abstract

Early residential mobility has known negative effects on mental health outcomes and academic achievement. These effects have been studied broadly and globally, yet there lacks attention in examining early residential mobility to specific localities, regions, or states. As such, this study sought to investigate these associations, specifically its impact on anxiety and academic performance in adults residing or living in South Carolina. Participants were surveyed online regarding their demographic information, academic performance, and anxiety levels. Results found no significant relationships between early residential mobility, anxiety, and academic performance among adults residing or living in South Carolina. Despite these null findings, research that further parses the relationship between residential mobility and negative outcomes is needed.

Moving America: A Study Examining the Relationships Between Early Residential Mobility, Anxiety and Academic Performance

It is estimated that Americans move 11.7 times throughout their life (US Census Bureau, 2018). For adults, moving residences often come from self-motivated desires associated with a life change. However, residential moving for infants and children may cause distress and disruption (Rumbold et al., 2012). While research on the late effects of early residential mobility has not been studied extensively, the body of literature on this topic has been recently expanding. Specifically, studies have suggested that early residential mobility can lead to higher risks of developing emotional and behavioral issues later in life (e.g., Jelleyman & Spencer, 2008; Mok et al., 2016; Oishi & Schimmack, 2010; Rumbold, et al., 2012).

Studies have begun to document the effects of childhood residential mobility on outcomes, such as academic achievement and mental health. Researchers conducted a longitudinal study of 8,337 students from 11 different schools within an urban Tennessee district (Voight et al., 2012). This study primarily analyzed administrative data that were collected across a span of six years. Results found that residential mobility, as measured by the number of address changes, in early childhood negatively affected performance on standardized reading and math tests (Voight et al., 2012). These findings were observed in as early as third grade academic performance. Another study was conducted to determine if there was a relationship between residential mobility before the age of 14 and the development of psychiatric disorders between adolescence and early middle age (Mok et al., 2016). These researchers conducted a population wide study of Denmark citizens, gathering data from 1,439,363 people. After acquiring approval from state agencies, data were compiled from registry and mental health records. Results found that higher residential mobility before the age of 14 was associated with a greater risk of developing psychiatric disorders in adulthood, particularly antisocial personality disorder and substance misuse disorder (Mok et al., 2016). Although other causes and directionality of these relationships continue to be understood, this study focuses on the relationship between early residential mobility and later outcomes measured in adulthood.

Considering the developmental and lifespan effects of residential mobility in childhood, some have examined how it affect adults. Researchers conducted a large study examining the effects of childhood residential mobility on well-being in adulthood (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). In this study, well-being was measured by life satisfaction, general psychological well-being, positive affect, and negative affect. Results found that early residential mobility negatively impacted well-being in those who were more introverted compared to those who were more extroverted. In addition, the researchers surprisingly found that introverts with residential mobility in childhood were more likely to have died within a 10-year period of the study (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). Moreover, a systematic review has documented the effects of childhood residential mobility on other health outcomes (Jelleyman & Spencer, 2008). In this review, a negative association between residential mobility in childhood and future outcomes such as behavioral, mental, and emotional issues was found (Jelleyman & Spencer, 2008). These findings illustrate a strong rationale to further examine the effects of early residential mobility.

Most of the research conducted on early residential mobility has focused on transregional moves. That is, few studies have specifically looked at the effects of childhood residential mobility on health outcomes within specific localities. One study sought to examine the relationship between local residential mobility and health (Larson et al., 2004). Using data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, researchers found that residential mobility within a single postal code was associated with poor mental health, having greater chronic diseases, and quicker decline in physical health in adulthood (Larson et al., 2004).

While studies have examined the impacts of moving in younger populations and in some non-US regions, this current study aims to add to the literature by examining childhood residential mobility in South Carolina residents. South Carolinians are a population that is seldom studied; thus, studies should be conducted to see whether national findings on early childhood residential mobility generalize to this population. This study focused on mental health outcomes, specifically anxiety, and academic outcomes, specifically collegial grade point average (GPA). Given previous literature, it is hypothesized that greater early residential mobility, as measured by self-reported moves before the age of 18, would be associated with elevated levels of anxiety and lower GPA.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited based on convenience, primarily through advertising in selected courses at the University of South Carolina and through the primary investigator’s social media platforms. The total number of participants was 41, including 6 males and 35 females. Most participants (n = 35) were between the ages of 18 and 25 years old. Two participants were high school graduates, 33 were current college students, and 6 had attained a college degree.

Materials

Google Forms, a public customizable surveying software, was used to produce the questionnaire. The first set of questions asked participants to provide general demographic information, such as biological sex, age and education status. Participants were then asked to provide their college GPA and the number of moves before the age of 18. To measure anxiety, a 7-item self-report scale sourced from the DASS-21 was used. All questions included from the DASS-21 can be found in Appendix A.

Procedures

All procedures were performed online. Participants were given access to a link to complete the survey and needed a secured internet connection to complete the survey. Informed consent was collected on the first page of the survey. The survey could be completed in approximately 2 minutes.

SPSS, a statistical software, was used to analyze the data. Two between-subjects ANOVA tests were conducted. The first test was used to determine the relationship between early residential mobility and anxiety, while the second test was used to examine the relationship between early residential mobility and academic performance, as quantified by GPA. A correlation between the two dependent variables was also conducted.

Results

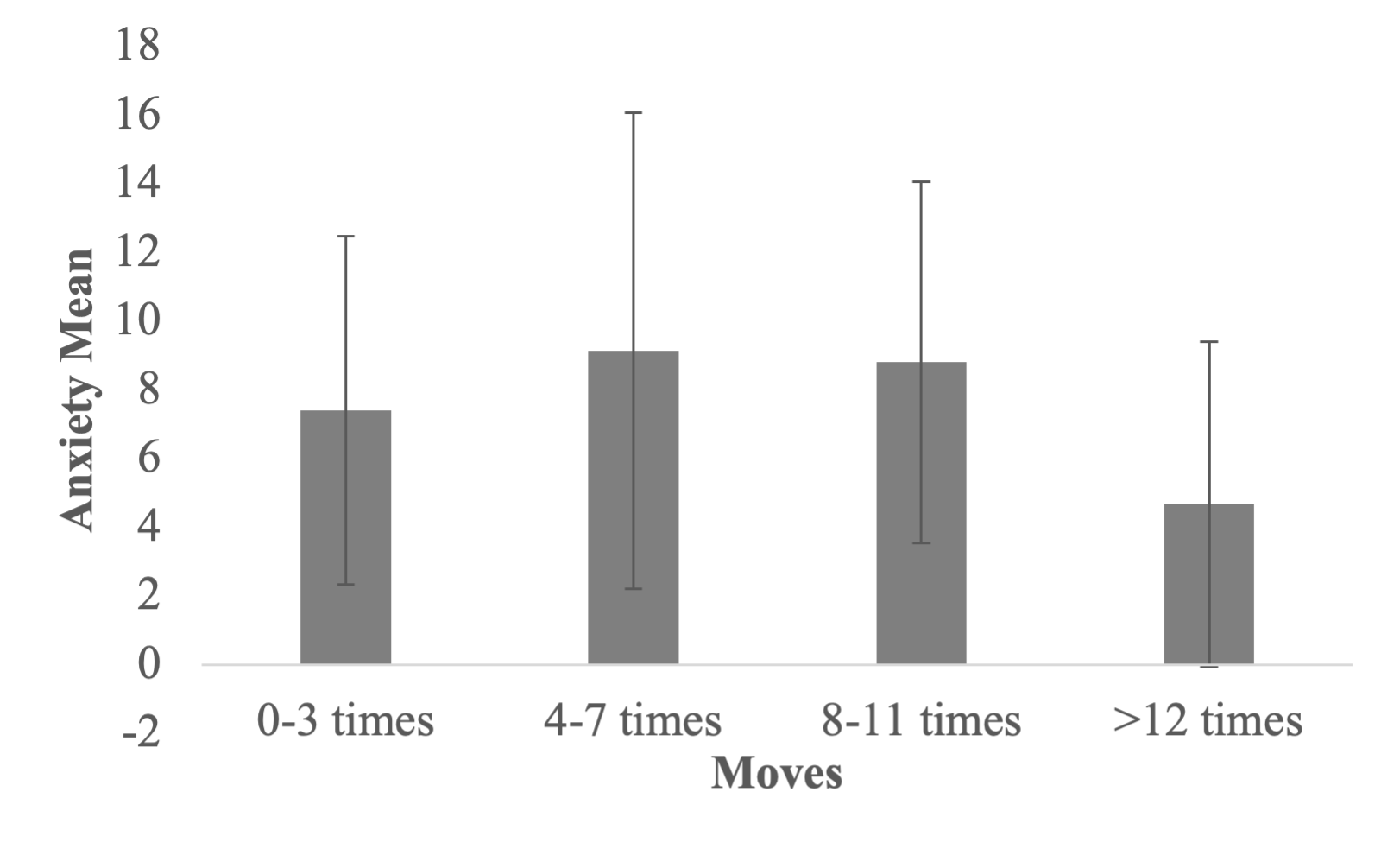

First, a one-way, between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to determine whether people who moved 0-3 times (M = 7.40, SD = 5.07), 4-7 times (M = 9.13, SD = 6.92), 8-11 times (M = 8.80, SD = 5.26), and greater than 12 times (M = 4.67, SD = 4.73) before the age of 18 had different anxiety levels. Results showed no significant difference in anxiety by number of times moved, F(3, 37) = 0.58, p = 0.63, η2 = 0.05 (Figure 1).

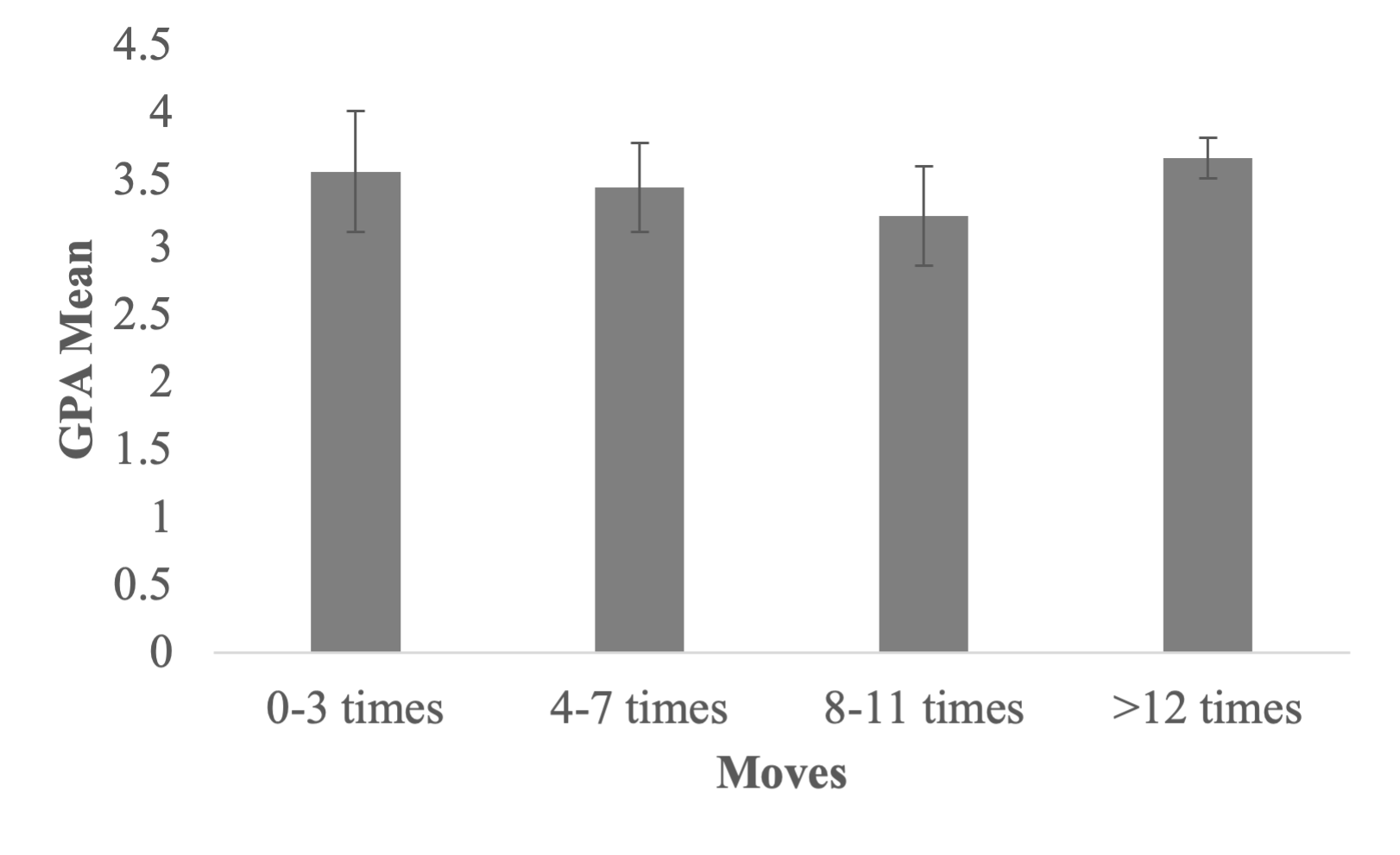

Second, a one-way, between-subjects ANOVA was conducted to determine whether people who moved 0-3 times (M = 3.57, SD = 0.45), 4-7 times (M = 3.45, SD = 0.33), 8-11 times (M = 3.24, SD = 0.37), and greater than 12 times (M = 3.67, SD = 0.15) before the age of 18 had different GPAs. Results showed no significant difference in GPA by number of times moved, F(3, 35) = 1.07, p = 0.37, η2 = 0.08 (Figure 2).

In addition, a correlation was conducted to determine whether there was a linear relationship between anxiety (M = 7.71, SD = 5.39), and GPA (M = 3.51, SD = 0.41). While the correlation was not significant, the effect size found was large, r(39) = -0.02, p = 0.90, d = 0.78.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between early residential mobility, anxiety, and academic performance in a sample of residents in South Carolina. From previous literature, it was hypothesized that early residential mobility would negatively impact both academic performance and mental health outcomes. Results did not support these hypotheses. Specifically, there was no significant differences in levels of anxiety or in GPA depending on how often an individual moved in early childhood.

This incongruency from prior research may be due to a variety of factors and limitations. First, the sample size of the study was small and was primarily comprised of college students, increasing the margin of error. Second, times moved were simplified into categorical ranges, limiting the scope of the research. Third, questions regarding times moved did not account for various move types, such as in or out of state, that could impact outcomes differently. Lastly, participants were not identified for personality types. Past findings assert that the wellbeing of introverts was negatively impacted by early residential mobility unlike extraverts (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). Conclusively, alternative stressors that may impact anxiety and academic performance, such as housing insecurity, were not considered in the scope of this study.

This study illustrates several points for future research. Given that this study did not find a relationship between early residential mobility and various outcomes in a sample of South Carolina residents, this raises the question whether this relationship is applicable to all locality in America. For example, a similar study conducted in North Carolina may yield results that are consistent with the overall evidence base. Another area for research is to examine potential mediators and moderators of this relationship. For example, there is evidence that suggest residential mobility is associated with family characteristics and variables, such as family structure and material demographics (Murphey & Moore, 2012). Lastly, future studies may examine the impacts of childhood residential mobility on other mental health disorders, such as substance use disorders or personality disorders. Overall, a greater understanding of the variables associated with early mobility and later outcomes may illuminate potential areas for intervention.

While this study did not find significant effects, it nevertheless encourages reflection on how residential mobility in childhood can affect our future well-being as contributing members of society. As these associations are complex in nature, with no clear causation, future studies will need to be complex and detailed to inform future interventions and solutions. With residential mobility being a notable part of American culture, further research will be promising in ensuring those who move early in life have the chances for the most optimal life outcomes.

References

Jelleyman, T., & Spencer, N. (2008). Residential mobility in childhood and health outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, 584-592.

Larson, A., Bell, M., & Young, A. F. (2004). Clarifying the relationships between health and residential mobility. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 2149–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.015

Mok, P. L., Webb, R. T., Appleby, L., & Pedersen, C. B. (2016). Full spectrum of mental disorders linked with childhood residential mobility. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 78, 57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.03.011

Murphey, D., Bandy, T., & Moore, K. A. (2012). Frequent residential mobility and young children's well-being. Washington, DC: Child Trends.

Oishi, S., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Residential mobility, well-being, and mortality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 980–994. doi: 10.1037/a0019389

Rumbold, A. R., Giles, L. C., Whitrow, M. J., Steele, E. J., Davies, C. E., Davies, M. J., & Moore, V. M. (2012). The effects of house moves during early childhood on child mental health at age 9 years. BMC Public Health, 12, 583. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-583

US Census Bureau (2018). Calculating migration expectancy using ACS data. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/topics/population/migration/guidance/calculating-migration-expectancy.html

Voight, A., Shinn, M., & Nation, M. (2012). The longitudinal effects of residential mobility onthe academic achievement of urban elementary and middle school students. Educational Researcher, 41, 385–392. doi: 10.3102/0013189X12442239

Appendix A

Citation: Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335-343.

- I was aware of dryness of my mouth.

- I experienced breathing difficulty (e.g. excessively rapid breathing, breathlessness in the absence of physical exertion).

- I experienced trembling (e.g. in the hands).

- I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself.

- I felt I was close to panic.

- I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion (e.g. sense of heart rate increase, heart missing a beat).

- I felt scared without any good reason.

Figure 1. Estimated marginal means of anxiety scores to early residential mobility.

Figure 2. Estimated marginal means of GPA to early residential mobility.