May 2009

“Build It Here!″ An Examination of Pride Versus Economic Motivations of Citizens Voting for Public Stadium Financing

- Scott Wysong, University of Dallas

- Philip C. Rothschild, Missouri State University

As new multi-million dollar professional sports stadiums and arenas are built every year in the U.S., the benefit of these facilities continues to be debated. Few would disagree that the professional team owner using the venue receives major benefits (such as increased revenues from new suites, amenities, etc.). However, there are widely varying opinions on the benefit to the community in which the stadium/arena is located. A number of economists have contended that a stadium or arena does not have a positive net economic impact on the community. Additionally, social and political activists lament the use of public monies to subsidize a private corporation (the team), considering the added traffic congestion and the local government’s ability to take private land from citizens (via eminent domain) to build the venue. Moreover, the lifespan of stadiums and arenas appears to be shortening as professional teams continually voice their preference for a new stadium or renovating their existing one. So, the question becomes “Why do citizens vote to use public money to finance (in whole or in part) professional sports venues?”

This paper will examine this issue by reviewing some of the previous literature, putting forth a conceptual model and analyzing the results of a survey conducted herein. The purpose of the survey was to capture what local citizens felt about an impending public vote for a new stadium for the Dallas Cowboys in Arlington, Texas. For several years, Cowboys’ owner, Jerry Jones, had been looking at various cities in the Dallas/Fort Worth area as potential sites for a new stadium. He then decided that he wanted to move the team’s home field to Arlington. In November 2004, a proposition was placed on the ballot in Arlington that was approved by voters, and the stadium is scheduled to open in 2009.

Review of Literature

A number of previous studies have examined the economic impact that sports and entertainment venues have on a local community. Solberg and Preuss’ (2007) article provides a comprehensive review of this literature and provides a framework for the definitions used in economic impact studies. In addition, Regan’s (1995) study provides a step-by-step methodology for measuring direct and indirect dollars related to a professional sports team. In his study, Regan concluded that the Denver Broncos contributed $117,801,500 to the greater metropolitan Denver area in the 1989–1990 season. No doubt this type of data enabled the team to secure millions in public financing for their new stadium: Invesco Field at Mile High.

Of course, for every positive impact study, there are numerous studies that decry the use of public moneys to finance a private team owner’s facility. One of the biggest critics of public financing is Zimbalist. In his 1997 book, Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, he writes:

Similarly, in a June 11, 2007 column in the Wall Street Journal, “A New Ballgame,” Herrick writes, “The overwhelming evidence is that sports venues put a drag on local economies by eroding spending on other activities and boosting municipal costs.”

With all of the previous studies examining the economic value of sports venues, very few researchers have measured the non-economic impact. Specifically, do sports and entertainment venues have a social impact? Do they create civic pride? Groothuis, Johnson and Whitehead (2004) investigated this issue when they surveyed fans in Pittsburgh about the pride they felt with each of the major franchises in town and several other city landmarks such as the Pittsburgh Zoo, Carnegie Mellon University and Heinz Hall. The authors conclude:

In another study, Wood (2006) developed a scale to measure civic pride with events. Using pre- and post-civic pride surveys in Blackburn, UK, she found that there is a “positive change in attitude after each event [small-scale community arts events].”

Altogether, previous researchers, as outlined above, have measured the economic and noneconomic effects of sports and entertainment venues. However, more research is needed to determine what motivates citizens to vote “For” or “Against” public financing of these venues.

Model

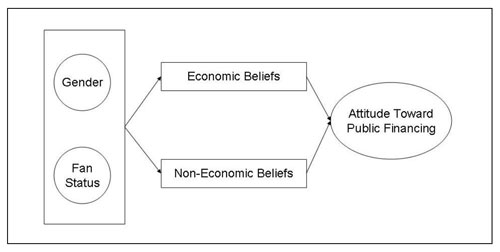

The aim of this research is to explore the basic motivations for voting for (or against) the use of public funds for a sports stadium. As illustrated in Figure 1, the model involves an individual’s gender and fan status (Are they a fan of the team?). In addition, the model incorporates two broad belief systems with regard to public financing. The first involves economic beliefs. Does the venue bring jobs? Does it fill the hotels and restaurants when hosting events? The second group of beliefs is noneconomic. Does the venue enhance the quality of life for the citizens? Do citizens feel proud to have the venue in their community? Lastly, how do these beliefs influence one’s attitude toward using public funds for a sports and entertainment venue?

Figure 1: Model of Citizen Attitudes toward Public Financing of Sports Venues

Methodology

Using a sample of graduate students at a university in the Southwest, 1,583 email surveys were distributed. Respondents were first asked if they considered themselves a fan of the Dallas Cowboys (Yes or No). Next, the respondents were provided with the actual ballot proposition for the proposed public financing of a new Dallas Cowboys stadium in Arlington which read:

Respondents were then asked three key questions:

-

- If you lived in Arlington, would you vote for this proposition (Yes/No scale)? Why or why not?

- A study commissioned by the city projected that the stadium could have a $238 million annual impact on the economy, which includes spending at local restaurants, hotels, shops and supermarkets. Do you believe that a new Cowboys’ stadium would have this kind of economic impact (Rating scale from 1=Not at All to 6=Definitely)?

- Regardless of the positive economic impact and/or the increased taxes, would you be proud to have the new Dallas Cowboys’ stadium in your city (Rating scale from 1=Not at All to 6=Definitely)?

Lastly, each respondent’s gender was collected.

Results

A total of 205 respondents completed the survey resulting in a 13% response rate. Sixty percent of the respondents were male and 50% considered themselves to be a fan of the Cowboys. In addition, 45% of the respondents indicated that they would vote in favor of the new Dallas Cowboys stadium in Arlington. To assess in detail the three key questions posited above, several analyses were conducted. These are detailed in the following paragraphs.

To examine the difference in beliefs (economic and non-economic) between Fans and Non-Fans of the Dallas Cowboys, two Analysis of Variances were run. In the first ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was FAN STATUS (Fan or Non-Fan) and the dependent variable was ECONOMIC. In the second ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was FAN STATUS (Fan or Non-Fan) and the dependent variable was PRIDE. As Table 1 illustrates, Fans had significantly higher ECONOMIC (F = 6.1, p < 0.0) and PRIDE (F = 46.0, p < 0.0) beliefs than Non-Fans.

Table 1: ANOVA Results for Fan Status

| Beliefs | Fan Status | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECONOMIC | Fan | 104 | 3.7 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 0.0 |

| Non-fan | 101 | 3.2 | 1.6 | |||

| PRIDE | Fan | 104 | 4.5 | 1.6 | 46.0 | 0.0 |

| Non-fan | 99 | 3.0 | 1.6 |

To examine the difference in attitudes between those who would vote for public financing of the stadium and those who would not, two Analysis of Variances were run. In the first ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was VOTE (Yes or No) and the dependent variable was ECONOMIC. In the second ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was VOTE (Yes or No) and the dependent variable was PRIDE. As Table 2 illustrates, those who intended to vote “Yes” for the new stadium had significantly higher ECONOMIC (F = 137.8, p < 0.0) and PRIDE (F = 99.0, p < 0.0) beliefs.

Table 2: ANOVA Results for Voter Status

| Beliefs | Vote | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECONOMIC | Yes | 93 | 4.6 | 1.1 | 137.8 | 0.0 |

| No | 111 | 2.5 | 1.3 | |||

| PRIDE | Yes | 91 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 99.0 | 0.0 |

| No | 99 | 3.0 | 1.6 |

To examine the difference in attitudes between males and females, three Analysis of Variances were run. In the first ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was GENDER (Male or Female) and the dependent variable was ECONOMIC. In the second ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was GENDER (Male or Female) and the dependent variable was PRIDE. In the third ANOVA, the factor variable of interest was GENDER (Male or Female) and the dependent variable was VOTE. As Table 3 illustrates, there were no significant differences between ECONOMIC, PRIDE and VOTE measures.

Table 3: ANOVA Results for Gender

| Beliefs | Gender | N | Mean | Std. Dev. | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECONOMIC | Female | 80 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Male | 121 | 3.4 | 1.7 | |||

| PRIDE | Female | 79 | 3.7 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Male | 120 | 3.9 | 1.8 | |||

| VOTE | Female | 80 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Male | 121 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

Finally, to look at the relationship between one’s economic and non-economic beliefs and their attitude toward public financing, a multiple regression was run. The ECONOMIC and PRIDE variables were the independent variables and the dependent variable was the VOTE variable. The results indicate that the overall model was significant (F = 81.0, p < 0.00). In addition, both independent variables, ECONOMIC and PRIDE, had a significant positive influence (B = 0.45 and B = 0.29) on VOTE.

Discussion

As with any research, there are several limitations to note. For one, the belief systems in this study were represented by very broad questions measuring believability of the economic impact numbers and the pride associated with a sports venue. Perhaps, in the future, more sophisticated multidimensional scales should be incorporated. Secondly, the sample used herein was a convenience sample and not citizens of Arlington (e.g., We asked, “If you lived in Arlington, would you vote for this proposal?”). Thus, future studies need to consider using exit polls to truly understand citizen attitudes. Lastly, a relatively simple statistical analysis was conducted in this study. Other analyses such as path analysis, discriminant analysis or logistic regression could be utilized in future studies.

In conclusion, this research reveals that fans of a team have stronger beliefs (i.e., higher ratings) in the impact of a sports venue’s economic and non-economic benefits than non-fans. This is not surprising. Similarly, those who indicated that they would vote “For” public financing of the stadium had stronger economic and non-economic beliefs than those who would vote “Against” public financing.

Once again, this is to be expected. However, there were some unexpected results. For instance, there were no differences in gender with regard to economic beliefs, non-economic beliefs and intention to vote for the stadium. Given that the group of fans in this study consisted of 70% males, it was believed that males would have stronger beliefs and attitude toward voting. This was not the case. Overall, though, the results of this study indicate that regardless of fan status and gender, both economic and non-economic (i.e., pride) beliefs had a positive influence on one’s vote for public financing. If a respondent believed the new stadium would have an economic impact on the city, they were more likely to vote in favor of public financing. If a respondent believed the new stadium would make them proud, they were more likely to vote in favor of public financing.

The results reported above reflect the need for team owners to generate marketing campaigns that balance economic and non-economic messages. In the future, researchers should study the actual marketing variables used in recent stadium / arena campaigns. That way, facility executives and academics would have a better understanding of the consumer behavior and marketing variables at work when promoting the need for a new facility.

References

Groothuis, P., B. Johnson and J. Whitehead (2004). “Public Funding of Professional Sports Stadiums: Public Choice or Civic Pride?” Eastern Economic Journal 30(4), 515-528.

Herrick, T. (June 11, 2007). “A New Ballgame,” Wall Street Journal. Noll, R. and A. Zimbalist (1997). Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, Brookings Institution Press.

Regan, T. (1995) “The Economic Impact of the Denver Broncos Football Club on the Denver Metropolitan Economy,” International Journal of Public Administration 18(1), 227-247.

Solberg, H. and H. Preuss (2007). “Major Sport Events and Long-Term Tourism Impacts,” Journal of Sport Management (21), 213-234.

Wood, E. (2006). “Measuring the Social Impacts of Local Authority Events: A Pilot Study for a Civic Pride Scale,” International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 11(3), 165- 181.

JVEM Editorial Board:

Editor: Mark S. Nagel, University of South Carolina

Associate Editor: John M. Grady, University of South Carolina

Consulting Editor: Peter J. Graham, University of South Carolina

JVEM Editorial Review Board:

Rob Ammon, Slippery Rock University

John Benett, Venue Management Association, Asia Pacific Limited

Chris Bigelow, The Bigelow Companies, Inc.

Matt Brown, University of South Carolina

Brad Gessner, San Diego Convention Center

Peter Gruber, Wiener Stadthalle, Austria

Todd Hall, Georgia Southern University

Kim Mahoney, Industry Consultant

Michael Mahoney, California State University at Fresno

Larry Perkins, BC Center Carolina Hurricanes

Jim Riordan, Florida Atlantic University

Frank Roach, University of South Carolina

Philip Rothschild, Missouri State University

Frank Russo, Global Spectrum

Rodney J. Smith, University of Denver

Kenneth C. Teed, The George Washington University

Scott Wysong, University of Dallas