“I am one of more than 30 million African Americans descended from American-born enslaved people who were emancipated in 1865,” says Pamela Bailey, documentary filmmaker and creator of The Antebellum Diaspora Project, which is locating and reuniting modern-day families separated by slavery.

As part of the project, Bailey, a Mullins, South Carolina native, is making an independent documentary film, Information Wanted: Reuniting an American Family Separated by Slavery in the Antebellum South. The film focuses on the forced migration of millions of American-born, enslaved people during the antebellum period, and the reunification of their descendants who share mutual ancestors.

“There are people walking around who have no idea how they are connected to each other,” Bailey says. “The descendants of slaveholders and the descendants of enslaved people are, for the most part, the same family.”

While Bailey lives in Dallas, Texas, she grew up in South Carolina near the places her ancestors had been enslaved. As a child, Bailey’s parents told her stories about her ancestors, but her family history truly came to life when she began doing research for her film.

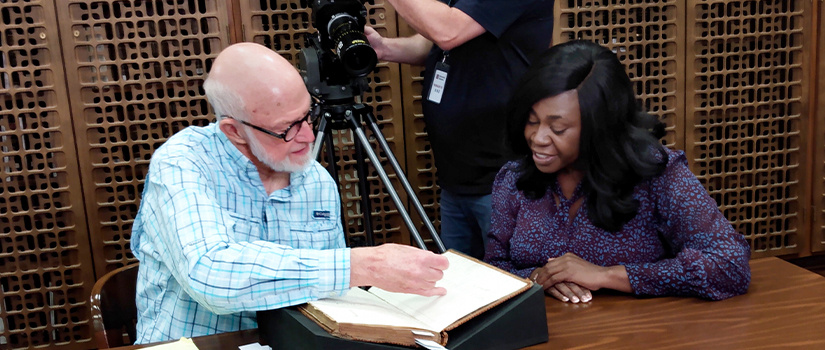

This past summer, Bailey, her film crew and her friend and fellow researcher Jim Watson visited UofSC’s South Caroliniana Library to research their shared family histories. Bailey and Watson discovered they were more than likely related after they first met at a lecture in Texas and swapped family stories. Meeting Watson, an attorney, scholar, professor of history and white man whose family enslaved Bailey’s ancestors, has helped Bailey piece together her own family tree.

“Meeting Jim in Texas and learning his ancestral family was connected to mine felt like a one-in-a-million chance,” says Bailey.

“After the lecture was over, Jim came over and introduced himself. He told me his family had been slaveholders in South Carolina, and that that they were from a place called Clarendon County, which is where my father’s family is from,” Bailey says.

While at the South Caroliniana Library, Bailey and Watson had the opportunity to read through a ledger belonging to one of Watson’s ancestors.

“Journals, ledgers and legal papers from slaveholding families can include the names of enslaved people, which is helpful in my search for my ancestors and their descendants,” Bailey says.

Historical records written by slaveholders can also serve to dispel long-held myths about the experiences of those who were enslaved.

“We can learn about the jobs beyond field work that were assigned to highly-skilled enslaved laborers whose services were often hired out to the benefit of the slaveholder,” Bailey says.

Historical records also provide insight into the lives of enslaved people. As Bailey and Watson carefully poured through the ledger at the Library, they read that the enslaved people on Watson’s family plantation were issued only one blanket every three years, regardless of weather conditions.

“And most importantly, we can see children born into enslaved families were assigned a value by the slaveholder, with the hope that the enslaved child would bring a financial benefit to the slaveholder’s family, from the cradle to the grave,” Bailey says.

South Caroliniana Library is a global destination for people doing genealogical research because it is one of the largest repositories of primary research resources in the nation concerning the history of South Carolina and the southeast itself.

“Since the story I am telling about the forced migration of American-born enslaved people and the reunification of their descendants is centered on my South Carolina family, the South Caroliniana Library has been a perfect fit for documents, pictures and family collections that are pertinent to the story,” Bailey says.

Historical documents help descendants of enslaved people determine where their families lived and where they were forcibly migrated to.

“These resources, along with my DNA testing, have helped me find my family across the U.S., and from South Carolina to California — literally from sea to shining sea,” Bailey says.

Graham Duncan, Head of Collections and Curator of Manuscripts at South Caroliniana Library, says the South Caroliniana Library holds a wealth of materials concerning the antebellum south and its economy, which was dominated by the institution of slavery.

“We have a large collection of records from white planter families from all over the state,” Duncan says. “A lot of records were produced by these families, whether it be plantation journals or family and business correspondence. But even things like church records can be critical to tracing one’s family roots in South Carolina.”

Bailey and Watson have become close friends through their kinship and research together. Though their families are connected through violence perpetuated through human enslavement, Bailey and Watson share a common goal: restoring a family that was shattered by forced migration.

“Jim’s family, the slaveholding South Carolina Witherspoon, McFadden and Montgomery families, lived in close proximity to one another, intermarried, and would have likely moved my enslaved ancestral family between their South Carolina plantations, and eventually moved them to other states where they also had plantations,” Bailey says.

“The reason we came to the South Caroliniana Library together is because Jim’s family is a very important part of this story,” Bailey says. “It’s important for me to include families on the other side of this history when they’re willing to share with us, and Jim has been amazing.”

“In Texas, I grew up hearing about cowboys and Indians,” says Watson.

Watson grew up not knowing that his ancestors owned enslaved people, and he didn’t know of his family connection to the southeastern U.S. But when his mother’s health began to deteriorate, she gave him something that opened his eyes to the reality of how his ancestors made a living.

“My mother went into her chest of drawers and pulled out a little, silver metal box with a lock and key and told me she wanted me to have it. When I got back to Dallas a few weeks later, I opened it and realized it contained the last will and testament of my great, great grandfather, who was a significant owner of enslaved people,” Watson says.

“He lived in Alabama, but also owned enslaved people in South Carolina. Alabama had just opened to farmers, so many enslavers in the east moved into that territory for good land, and they moved their enslaved people with them. This was all startling to me — an enormous surprise because there had never been any discussion of it in my family,” he says. “I wanted to learn more about it, then along came Pamela.”

Duncan says plantation records from very large estates, like the ones Bailey and Watson examined at the South Caroliniana Library, were produced for very specific reasons — for owners of enslaved people to keep track of their human capital, land and plantings. Because of the wealth of information about enslaved people within plantation records, the South Caroliniana Library has many patrons who work with the collections and research African American history, their families or the institution of slavery.

“We field a lot of requests for African American families from all over the country doing genealogical research because of our large collection of antebellum records,” Duncan says. “The South Caroliniana Library is one of the premier stops for people doing that type of research.”

Anyone can access and examine, in person, the historical records, journals, ledgers, manuscripts, letters and other ephemera at South Caroliniana Library. Its patrons come from all walks of life and are not limited to academic researchers. But people interested in doing research at the Library are encouraged to reach out to the Library staff before they visit to discuss what they’re looking for so the librarians can provide them with the best selection of resources during their visit.

“Anyone planning to use the South Caroliniana Library for research should make a plan,” Bailey says. “They should talk with the Library’s team and discuss what kinds of documents they are looking for. The staff at the South Caroliniana are knowledgeable, and when I reached out to them, they quickly assessed that they could be of help to me.

“They have been professional, supportive and accommodating to help me tell this important and emotional story,” Bailey says. “The South Caroliniana Library has resources that can help restore families that have endured up to 20 generations of family separations. Families can be restored with the right resources, and the South Caroliniana Library is one of the best in the nation.”