Walking into the Columbia, S.C., publishing company Layman Poupard is like walking

into a literary museum. Photos, books, memorabilia and letters of major literary figures

are everywhere, including artifacts related to renowned 20th-century detective-fiction

writer Dashiell Hammett. Most of Richard Layman’s Hammett material, however, now lives at the university’s Irvin Department of Rare

Books and Special Collections.

Walking into the Columbia, S.C., publishing company Layman Poupard is like walking

into a literary museum. Photos, books, memorabilia and letters of major literary figures

are everywhere, including artifacts related to renowned 20th-century detective-fiction

writer Dashiell Hammett. Most of Richard Layman’s Hammett material, however, now lives at the university’s Irvin Department of Rare

Books and Special Collections.

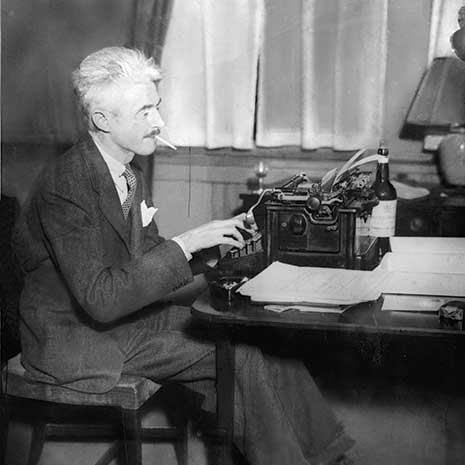

A long-time bookman and friend of University Libraries, Layman started his journey of studying and writing about Dashiell Hammett when he came to USC in 1972 to get his doctorate in English. “I wanted to learn from people who cared about bibliography, book collecting and the facts regarding literary creation," Layman says. "And USC had an English department that excelled in those fields.”

His professor, friend and later business partner, Matthew Bruccoli, who first attracted him to the university, asked him to research and write a bibliography on Hammett. “I didn’t really have a specific interest in Hammett to begin with; that grew with time. But I came to deeply respect and admire Hammett and his work,” Layman says.

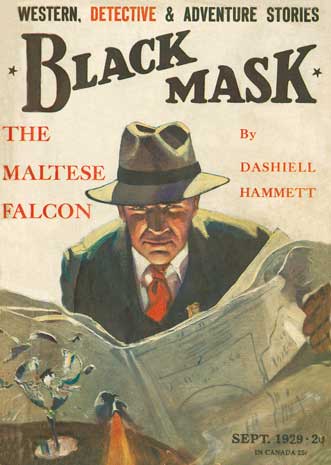

Hammett, born in the late 19th century, lived most of his early life in poverty. He interrupted his career as a Pinkerton detective to join the army during World War I, where he contracted influenza and was discharged as medically disabled. Unable to resume his career, he turned to writing for pulp magazines, primarily Black Mask. “During the ’20s, he was close to destitute, writing for little more than a penny a word,” says Layman.

By the end of the decade, Hammett had earned a reputation as the best of the Black Mask writers but had grown tired of grinding out what he called “junk.” In 1930 he wrote a remarkable letter to his editor saying, “Someday somebody’s going to create literature out of detective fiction.” “And with his novel The Maltese Falcon, published that year, he did it,” says Layman. That novel changed his life.

In just three years, Hammett went from living in poverty to wealth beyond his dreams

— which he spent lavishly on alcohol and a reckless lifestyle. He joined the Communist

Party, served in the army during World War II, and was targeted during the McCarthy

era for his political beliefs. He died a poor man in 1961, leaving behind complicated

relationships and a literary legacy for Layman and Hammett’s family to comb through.

In just three years, Hammett went from living in poverty to wealth beyond his dreams

— which he spent lavishly on alcohol and a reckless lifestyle. He joined the Communist

Party, served in the army during World War II, and was targeted during the McCarthy

era for his political beliefs. He died a poor man in 1961, leaving behind complicated

relationships and a literary legacy for Layman and Hammett’s family to comb through.

One biography and nine other books on Hammett later, Layman decided to have his Hammett collection live at USC — joining the archives of other famous crime-fiction writers, including Elmore Leonard, James Ellroy and George V. Higgins. Layman’s scholarly work on Hammett also led over the years to the development of a close relationship with the writer’s surviving family members, and when he agreed to send his Hammett archives to USC Special Collections, the Hammett family did likewise.

“The acquisition of the Layman-Hammett Collection and the Hammett Family Collection have drawn international attention to USC Libraries as a repository for crime fiction material,” says Elizabeth Sudduth, associate dean for special collections. “This acquisition would not have been possible without Rick Layman.”