Professor Creates Lyrical Responses to Exhibit Photographs

Nikky Finney, the John H. Bennett, Jr. Endowed Professor of Creative Writing and Southern Letters, was commissioned to write poems based on photographs in the “SOUTHBOUND” exhibit at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art at the College of Charleston. The result is an electrifying dialogue—powerful poetic meditations on southern visual history.

As Professor Finney describes this “once-in-a-lifetime project”:

When the organizers of SOUTHBOUND contacted me about composing one ekphrastic poem for the exhibit, I wasn't sure I had time to do it. Then they sent me the photographs to peruse…The images hit me like a ton of bricks. The photographs rocked me, hugged me, made me sit up straight, lean forward. The southern landscape being photographed was my land and I had never seen it so naked, so revealed, so revelatory. Art does this to us. The power of revelation and candor was on every page. I ended up submitting 4 poems instead of one and I could have submitted 12.

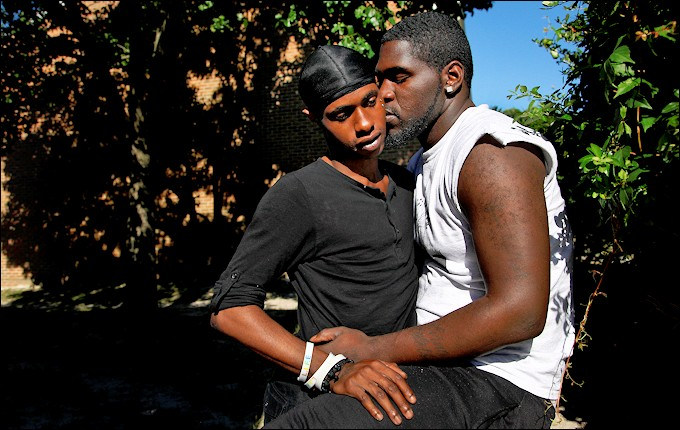

In this dialogue, Finney’s sensuous love prose-poem is framed in southern greenery:

|

Preston Gannaway |

Magnolia Garden Homes, High Noon,Unit #144, Parking Lot HThick kudzu arm lover, the one who gives my thighs their bass |

A woman wielding garden hoe and pen rewrites Hurston’s image of black womanhood in Their Eyes Were Watching God:

Black Woman Moose Lodge #719(Ludie Mae Green edits the great Zora Neale Hurston with one stroke of her orange hoe) On this wooden bench I have learned to pray for myself first. I will find. Just last week I came upon a book pulling me over to it it tight. It was the great story of Eyes and God by the great Negress like I had found an old friend. And soon there it was – still breast-high, Just to see those words again, rising off the page like field smoke, words the memory of all that made me throw that sweet book, cover and all, say the great Negress authoress had hooked me once again. I picked it and reading, circling back to read some more, just to have the word-lights end of me to the other. Inside the rich red soil of her words I feel pulled away the okra and green beans of my garden. Even now as I sit here with my magic that a writer of her knack needs to know the effect she is still having on the Dear Miss Zora Neale Hurston, Yours, Most Truly and Most Sincerely, Ludie Mae Green |

Rachel Boilliot |

A young boy revises his ideas of masculinity and fatherhood as he proudly displays a treasured belt:

Titus Brooks Heagins |

Little Man Standing in CloverI come here to think not smile. Cut that. Green is my granddaddy’s favorite color. I like to think about was born before me. granddaddy takes his shirt off in the sun. for me to be a man and that’s when mama was listening, “prayer.” I never come here Uh-uh. Cut that. A man needs his belt when Ain’t scared of no snake. Cut. That. I got says a man should keep his chest out in the grow and his eyes won’t run. Daddy says he can wear it to church on Sunday then the difference. Cut that. Smiling is for |

The most poignant juxtaposition takes place between a photograph of an environmental disaster and Professor Finney’s poem on the Charleston church shooting of 2015. As she explains:

For over a year I had been trying to write a poem about the Mother Emanuel massacre. When I saw Daniel Beltrá's photo of Oil Spill #12 in the SOUTHBOUND catalogue, I knew this photo was—for me—the most accurate visual representation of longing and loss that I had been feeling about the Charleston massacre. I also knew what I wanted to say had something to do with Miss Polly scrambling underneath the collection table when the shooting began. I watched and listened to her heart-stopping testimony at the trial last summer. I had tried but couldn't find my way into what I wanted to say about it all. Then—I saw the photo and it somehow reminded me of Miss Polly's testimony. It reminded me of that haunting moment when Dylan Roof asks Miss Polly, “Have I shot you yet?” The incredulity at such a question being asked in such a moment like that. I knew immediately the question he asked and her immediate answer would be the bookends of the poem I hoped to compose.

Miss Polly Is Akimbo Underneaththe Mother Emanuel Collection TableThe one who came to start the next Civil War akimbo to the eight others who are sprawled and A floating band of iron orange tincture crooks her and blue unsure of what has been released in the this one has done. She decides her last words on self perfectly still, asked her body to lie for her but their safe skins, her persimmon words outline every beloved |

Daniel Beltrá |

Professor Finney’s poems are only part of the dialogue sparked by this amazing exhibit. She continues:

I was so moved by the entire body of SOUTHBOUND work that I got my MFA graduate students involved. When I am looking for subjects to teach and share with my students, they are never far away from my own immediate outrage or joy. I made ekphrastic assignments to my MFA class and they began to swim through the images and work on their own interpretations of the photographs. When I casually shared this assignment with the organizers they wanted my students and their work to be part of the opening festivities. So we made a plan and drove over one Saturday last October. Six USC MFA poets/students were given the spotlight. I think it was an amazing moment for them. It was for me. They wrote beautiful memorable poems. They rose to the occasion with their pens and imaginations. They read with power and grace.

See, too, the Lenscratch article:

http://lenscratch.com/2019/03/southbound-photographs-of-and-about-the-new-south-day-2/