Environmental studies and anthropology professor explores justice of climate change and public policy

By Bryan Gentry | August 11, 2020

Rising tides bring up big questions for Monica Barra.

Questions such as why climate change hits some communities and cultures harder than others, or how government policies sometimes create more inequality in coastal communities.

She has studied these questions in Louisiana for years. Now an environmental studies and anthropology professor at the University of South Carolina, she is bringing her work to the Atlantic Coast. As South Carolina engages in more climate change planning, there’s a chance to get the policies right, she says.

“I think there is an opportunity, but it will take a radical shift in our collective imagination of what climate-changed futures can look like,” Barra says, explaining that the state needs more diverse voices in the process. “How would programs and relationships between the coastal environment and residents look different if leaders from various African American, Indigenous, Latinx, or other communities were envisioning it?”

Barra hopes to build collaborations that bring more voices into conversations about environmental policy. She will do that with the support of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The organization awarded Barra a two-year fellowship in its Gulf Research Program Early Career Research Fellowship. The grant supports researchers who have an interest in the Gulf Coast as they continue their research. Barra is writing a book about her work along the Gulf Coast while expanding her work to South Carolina and Georgia.

You can have all the best science in the world, but if you don't understand the social and political conditions, you're not going to be able to see the impact of your science.

— Monica Barra

She is a cultural anthropologist interested in race and environmental justice, looking at how environmental degradation and policies are a boon to some communities and a burden to others. This fall, she is teaching a course on Environmental Justice for the College of Arts and Sciences Theme Semester.

Her dissertation focused on land loss in Louisiana, pointing out that there was more involved than rising sea levels and erosion. Working on the ground with residents, policy makers, legal experts and others, she saw how environmental problems impacted black residents and indigenous communities more heavily than white counterparts.

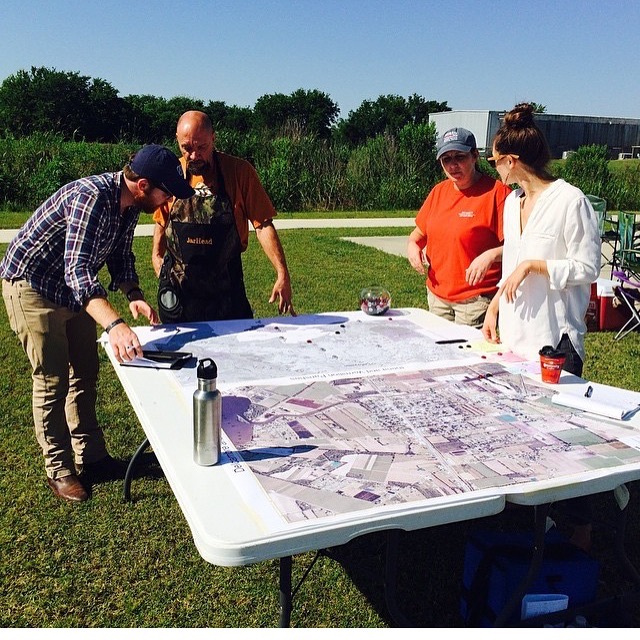

Monica Barra talks a bout an environmental project in Louisiana.

She says it makes sense to discuss science, technology, engineering, racism, culture and law together, because those dimensions affect how society grapples with environmental change, from the conception of policy to the construction of solutions.

“It’s not just about the engineering of the levee,” she says, referring to the levees that burst in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, flooding minority communities. “That doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens in a particular political environment, and it impacts particular groups of people."

“You can have all the best science in the world, but if you don't understand the social and political conditions, you're not going to be able to see the impact of your science.”

In South Carolina, Barra wants to explore heir property laws, which govern how land is divided among the descendants of a person who dies without a formal will. As land is inherited over several generations, “you get this situation where there are hundreds of people who own a property,” Barra says. That situation has often been leveraged to allow people or corporations to take land from families at below-market rates. Get one of the part-owners to sell, and a court may decide the fate of the land.

I think there is an opportunity, but it will take a radical shift in our collective imagination of what climate-changed futures can look like.

— Monica Barra

But heirs property laws also affect climate change planning, Barra says. Many federal programs that help people prepare for climate change — such as raising their homes to reduce the risk of flood damage — require a person to show clear title to their property, something that is not possible under heirs property laws. Unless those policies are updated, then climate planning programs are unavailable to families whose cultures employ less formal methods of owning and inheriting land.

“You can't talk about climate change planning without understanding the unique relationships that people have to land and landownership,” she says.

Barra is working with a graduate student, Teresa Norman, who is researching racial justice and climate change planning in South Carolina, and they plan to start outreach soon to discuss heirs property laws and other issues. “We’re aiming to do more with planners, legal aid groups and landowners over the next year,” she says.

Barra is an assistant professor of environment and race in the School of the Earth, Ocean and Environment with a joint appointment in the Department of Anthropology. She is a faculty affiliate in the African American Studies Program.