Introduction

In 2008, the Maritime Research Division (MRD) was awarded an American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) grant administered by the National Park Service to study the naval and combined operations at the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield during the American Civil War. The ABPP provides these funds to encourage preserving and protecting battlefields and sites that influenced American history, promoting and assisting in preservation management and planning of these sites, and increasing awareness and appreciation of preserving these significant battlefields and sites for future generations. Funds from the ABPP grant allowed the MRD to undertake historical research and archaeological investigations on cultural resources remaining on the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield, the scene of a protracted struggle from 1861 to 1865 between Confederate defenders and Federal attackers. Through archaeological remains and historical research, the project aimed to identify the boundary, and the various core and defining features of the battlefield, namely the wrecks of ironclads and blockade runners, now-submerged land batteries, and obstructions. To accomplish the goals of defining the battlefield boundary, the accurate positioning and extent of the associated features required the use of Differential Global Positioning System (DGPS) and a variety of non-disturbance remote sensing technologies. Historical and previous archaeological research guided field operations to pinpoint known sites, and to survey for historically-documented battlefield related cultural features. Research and field operations undertaken to identify these known and potential features from both sides of the conflict served to develop a more complete understanding of the battlefield to aid in the interpretation and preservation of these Civil War resources.

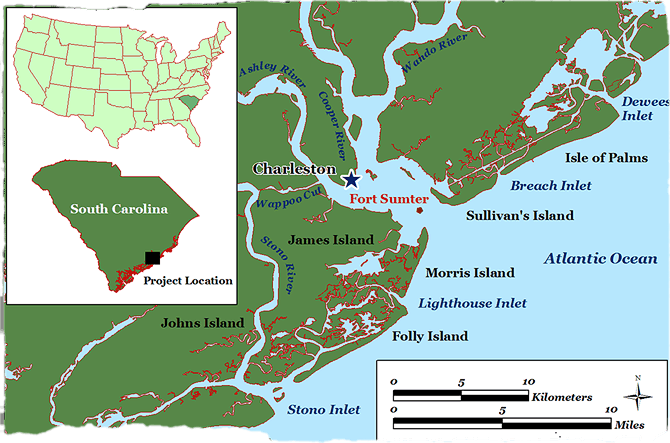

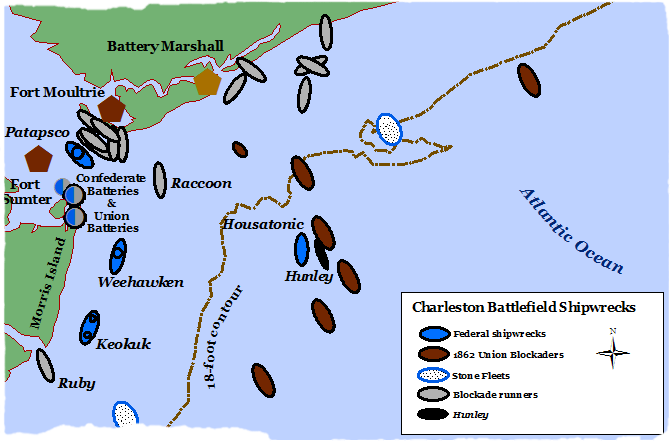

Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield project area

Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield project area

Historical Sketch of Charleston

In 1670, a colonial expedition of English settlers sailed to present-day Charleston Harbor and founded Charles Town (re-named Charleston in 1783). Named in honor of the King of England, Charles II, the town developed into an entrepôt for the exploitation and exportation of natural resources, furs—primarily deerskins, and naval stores to England. Originally settled on the west bank of the Ashley River on Albemarle Point, the town relocated in 1680 to Charleston Neck, a peninsula formed by the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. These two rivers join to form Charleston Harbor with outlet to the Atlantic Ocean. A move intended to expand and create shipping opportunities for the growing and prosperous colony. In the intervening years prior to the Revolutionary War, Charleston flourished as trade transitioned from a natural to an agricultural-based economy centered on indigo, sea island cotton, and rice cultivation using African slave labor. The Carolina colony, with Charleston as the epicenter, became one of the richest colonies in the British Empire as a result of the large rice plantations centered on the upper reaches of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. The move for independence from England in 1776 brought ruin and deprivation to the port. Repelling a naval and land assault in late June 1776, American troops and militia in the city capitulated to British arms in 1780. Remaining under British domination until the war ended in 1783, the port languished as a trading backwater.

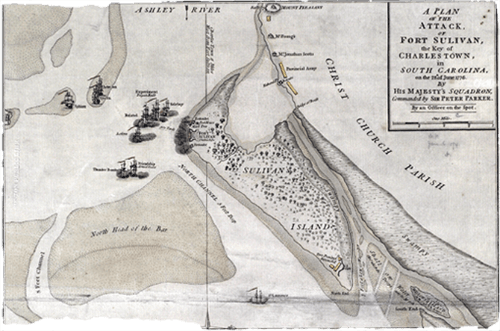

British navavl forces attacking Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island in 1776

Under the new Federal government, Charleston slowly recovered its preeminence as a southern trading port, relying on the exportation of rice and cotton as the mainstay of its economic vitality. The War of 1812 temporarily disrupted shipping and economic development as British privateers preyed on American shipping along the southern shores. Although returning to normalcy and continued prosperity after the cessation of the war, the next several decades saw the gathering clouds of discontent concerning the economic development of the city, South Carolina, and the South. Issues of great national import created heated political discourse in relation to the role of the Federal government vís a vís State government. The first issue centered on Federal tariffs on foreign trade, greatly impacting imports and Charleston’s economic lifeblood. South Carolina passed an Ordinance of Nullification in 1832, allowing the state to override the Federal tariff. In response, Federal revenue cutters and troops were deployed to collect the fees in Charleston. The predicament finally ended with a repeal of the State ordinance and revisions to the Federal tariff. The next national crisis in the late 1850s and early 1860s—the question of slavery would not end so peaceably. Led by South Carolina, a cascade of southern states drafted and enacted Ordinances of Secession from the United States in late 1860 to early 1861. These newly independent states joined to form the Confederate States of America in the beginning of 1861. So as the first ordinance of secession was signed in Charleston, so to the first shots of the American Civil War erupted from the city onto Fort Sumter.

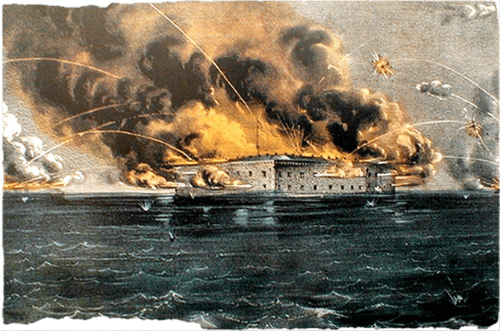

Fort Sumter under Confederate bombardment in 1861

Charleston Harbor During the Civil War

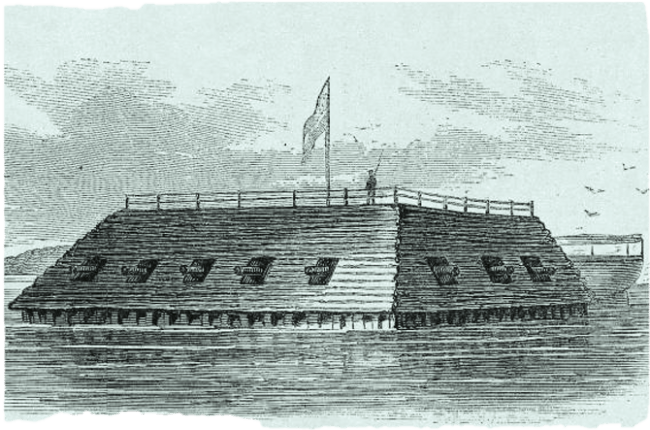

From the first shots upon Fort Sumter on 12 April 1861 to the evacuation of the city by Confederate forces on 17-18 February 1865, the port became the scene of a protracted struggle between land and naval forces. Following the announcement of secession from the Union on 20 December 1860, State and then Confederate forces strengthened military positions around Charleston Harbor. Political and military authorities had two outcomes in mind: one, to force the withdrawal of the Federal garrison in Fort Sumter, and two, to prevent relief operations from aiding the beleaguered forces in the fort. To force the abandonment of Fort Sumter, a number of pre-existing forts were strengthened for action: Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, Fort Johnson on James Island, and Castle Pinckney, just off Charleston in the harbor. All of these forts ringed, with their guns directed towards, Fort Sumter. New construction of a string of defensive earthen works along the main harbor entrance on Sullivan’s Island augmented Fort Moultrie. At the northeastern tip of Morris Island, Cummings Point, and along the beach fronting the Main Ship Channel, several batteries were erected. The Cummings Point guns were directed at Fort Sumter, while those along the channel in the Atlantic Ocean were meant to thwart entrance into the harbor by Federal vessels. A Floating Battery situated inside the harbor between Sullivan’s Island and Mt. Pleasant, along with armed launches and steamers, added a naval component to the terrestrial preparations. Expecting the arrival of a Federal relief expedition, Confederate forces commenced fire on Fort Sumter in the early morning hours of 12 April. The bombardment lasted for approximately 33 hours. Satisfying his duty and obligation to his country, Major Robert Anderson surrendered his command of the fort to the Confederacy the next day.

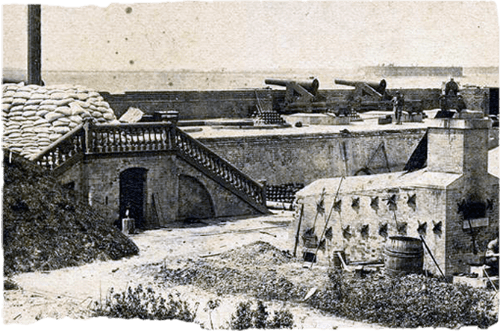

Fort Moultrie preparing for action against Fort Sumter looming in the background

Following the capitulation of Fort Sumter, Confederate and State military authorities now directed their attentions to protecting themselves from the expected Federal invasion force bent on subduing the city. General Pierre G. T. Beauregard, commander of Confederate forces in Charleston anticipated five potential Federal avenues of approach to attack the city. He ordered the construction of a series of earthen work forts and batteries at key points stretching from Bull’s Bay to the north and to John’s Island to the south to ring the city. Two water avenues, Charleston Harbor, provided direct access to the city, while the Stono River on the southern flank, afforded a backdoor entrance to the city through Wappoo Cut and then into the harbor. To prevent an Union naval assault via these water passages, critical Confederate defenses were centered on the sea islands south of the island, primarily James, John’s, Cole’s, Folly, and Morris Islands, and north of the harbor, Sullivan’s Island. General Robert E. Lee assumed command after Beauregard was ordered north to prepare for the upcoming First Battle of Manassas. Continuing to implement the basic defensive cordon around Charleston, Lee’s major contribution to the defenses of the city was to realize the superiority of naval guns over field batteries in regards to range, especially those along the Stono River. He ordered the placement of the batteries on James Island more towards the Ashley River side, or northern side. This in effect conceded a landing and staging area to a Federal force, but more prudently, kept the Confederate earthen works and any counter-offensive force out of direct covering fire from the gunboats. Lee gave way to General John C. Pemberton, when he was ordered back to Richmond.

Pemberton continued the fortification of the low country and the city as outlined by Beauregard and Lee. He, however, made one change that angered many in the city and the state—abandoning the battery established on Cole’s Island at the mouth of the Stono River. Prior to this move, the southern defensive line of the city, and thought the most likely Federal route of attack of taking James Island via the Stono River, stretched, island-wise, from James’s Island and pivoted on Cole’s Island, both on the Stono River. The line then veered northeast with Folly Island and Morris Island along the Atlantic Ocean, and then over the entrance of Charleston Harbor to Sullivan’s Island. Withdrawing the battery from Cole’s Island in effect removed the keystone island linking the Stono River defenses with the Atlantic Ocean defenses. Many argued that this essentially provided a toehold for Union troops to attack James Island and to open the Stono River for marauding Federal gunboats, both of which in fact happened. Pemberton argued the move was tactically sound—to prevent the capture of the guns and garrison on Cole’s Island. His opponents argued the move was strategically unsound—he had opened the door for Federal attack. Losing his command over this issue, Pemberton assumed a post out west, while Beauregard returned to once again to work on strengthening the defenses for the impending strike at South Carolina and Charleston.

Confederate preparations to counter a direct thrust into Charleston Harbor, the main defense against a Federal naval assault relied on the coastal forts and batteries, and physical obstructions. Fort Sumter, along with Fort Moultrie and a number of earthen works along the harbor-side of Sullivan’s Island, formed a protective outer harbor defense. An inner harbor defense consisted of Fort Johnson on James Island, Fort Ripley on a man-enhanced islet in the middle of the harbor, Castle Pinckney, a couple of batteries at Mt. Pleasant, and a series of earthen works haloing the city itself. Besides relying on the many guns protecting the harbor, Beauregard ordered the fabrication of physical obstructions to the harbor entrance. A log-boom stretched from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter, with a small opening for blockade runners to enter the harbor. This obstruction proved troublesome to maintain, and was abandoned in favor of a series of rope entanglements and torpedoes to thwart enemy attack at various points in the harbor. While the Confederates had armed a few steamers prior to and just after launching hostilities, there were no true warships stationed in the harbor until the fabrication of three ironclads, CSS Chicora, CSS Palmetto State and CSS Columbia. Clad in iron rail road tracks, these vessels were under powered and served mainly as floating gun platforms inside the harbor. Although, the ironclads CSS Chicora and CSS Palmetto State in consort with two wooden steamers did, however, make one aggressive sortie which resulted in a temporary break in the Federal blockade. After this successful counter-offensive move, the ironclads remained in station in the inner harbor providing support for the outer defenses, primarily acting as a deterrent to Federal aggression. Two novel approaches were undertaken by the Confederates to contest Union naval superiority. The first involved a semi-submersible-class of vessel called Davids, and a true submarine, H.L. Hunley. Both vessels launched offensive action against the Union fleet off Charleston, only one, the Hunley, sank another ship, USS Housatonic, while a David did succeed in detonating a spar torpedo against the hull of USS New Ironsides, and although damaging the warship’s hull failed to cause it to retire from its station.

Confederate harbor steamboat at Fort Johnson with Fort Ripley in background

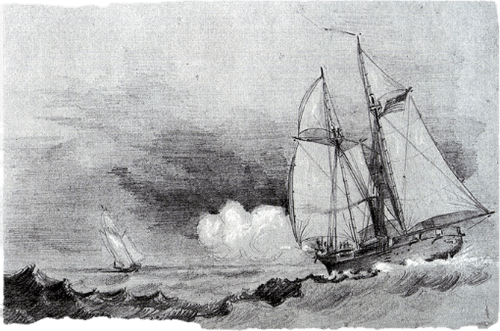

Federal naval strategy at Charleston evolved initially from blockading the port to actively participating in combined operations with the army and in launching strikes against Confederate defenses. The role of the navy changed after the second great Union invasion expedition captured Port Royal Sound in late 1861, located between Charleston and Savannah. The facilities at the sound provided a convenient logistical point for both the army and navy from which to maintain the blockade and most importantly, launch attacks against Charleston and other coastal destinations. Building a presence off the harbor, the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, primarily composed of wooden vessels, patrolled the waters to prevent the departure of contraband goods, i.e., cotton, rice and naval stores, and the arrival of military supplies and other goods. In an effort to close off the two main channels into Charleston Harbor, the Main Ship Channel and Maffitt’s (or Beach) Channel, 29 ex-whalers and merchant vessels from New England were sunk in two separate ventures, the First and Second Stone Fleets. Quickly consumed by the shifting sands at the two channels, the stone fleets failed to keep blockade runners at bay. The majority of blockade runners attempting to run the blockade succeeded, primarily using Maffitt’s Channel, which was protected by Confederate land batteries on Sullivan’s Island. A number of them, however, were interdicted or destroyed when they grounded and then subsequently pounded by Union naval and or land fire to prevent their valuable cargoes falling into the hands of the Confederates.

Union blockader chasing a blockade runner

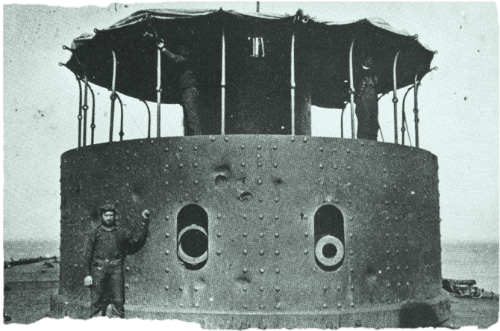

Offensive capability manifested itself with the arrival of several ironclads in early 1863. Under pressure from Washington, Rear-Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont, commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, ordered an armored thrust into Charleston Harbor with the objective of attacking Fort Sumter. On the afternoon of 7 April 1863, the Federal fleet of eight ironclads and the New Ironsides steamed through the Main Ship Channel and into the throat of the harbor. Awaiting the invasion fleet and anticipating this day for several years, the Confederate artillerists, protected in a series of fortified forts and earthen works armed with heavy ordnance, with ranges marked by buoys, opened fire as the ironclads entered the harbor. Approaching within 900 to 1,300 yards of Fort Sumter, the ironclads, near point blank range from the Confederate artillery, concentrated their fire on Fort Sumter. Persevering through the destructive iron storm of Confederate shot and shell, the ironclads pressed their attack for over two hours before withdrawing. Heavily damaged the fleet returned to its anchorage off the southern end of Morris Island to regroup and to make repairs for another attack. During the evening, the riddled ironclad Keokuk sank from battle damage sustained that afternoon. A council of officers decided not to re-enter the harbor with their damaged ironclads, and the ironclad fleet disbanded several days later to Port Royal and up North for repairs. This was the last and only direct naval assault against the harbor. Although, the navy did attempt one more attack against Fort Sumter, using barges armed with sailors in late 1863. A costly failure, the Confederates easily beat back the attack.

Turret of monitor USS Passaic showing effects of 7 April 1863 attack on Charleston Harbor

Following the ironclad attack which cost Du Pont his command, the blockaders settled back into preventing blockade runners from entering the harbor. The arrival of new Army and Navy commanders, bent on capturing Charleston, signaled the advent of another attempt, this time in combined operations, to capture the city in mid-1863. As a prelude to their plan, General Quincy Gillmore and Rear-Admiral John Dahlgren joined forces to attack Confederate positions on Morris Island. The navy directed enfilading fire from offshore the island at the two main Confederate batteries on the island: Battery Wagner, and Battery Gregg at Cummings Point. As the Federal troops launched several unsuccessful and costly direct assaults on Battery Wagner, the monitors, USS New Ironsides, and wooden gunboats directed heavy fire at the battery. Resorting to sapping to gain the battery, the troops labored to create a series of parallels and batteries under a protective barrage maintained by the Union fleet. Anticipating the battery and island were no longer tenable to hold; the Confederates abandoned their works on the night of 6 September 1863.

Monitor fleet pounding Battery Wagner in 1863

While the Federal troops worked on capturing Morris Island, they also directed their attention to bombarding the city of Charleston and Fort Sumter. Fabricating a battery in the marsh between Morris and James Islands, and nicknamed the “Swamp Angel”, a 200–pdr. Parrott rifle launched projectiles at the city from 21 August 1863 until early 1865. Federal guns from the land batteries on Morris Island and the ironclads combined to reduce Fort Sumter from a defensive weapon armed with a multitude of heavy guns commanding the harbor entrance into a mere infantry outpost. Despite the Army’s claim that the battered fort offered no impediment to a naval incursion against Charleston, the navy hesitated deeming the fort, along with the obstructions consisting of ropes and torpedoes strung between the fort and Sullivan’s Island, an obstacle to taking the city. Despite the capture of Morris Island and a reduction in the defensive capability of Fort Sumter, Federal land and naval forces remained stationary off Charleston Harbor until early 1865.

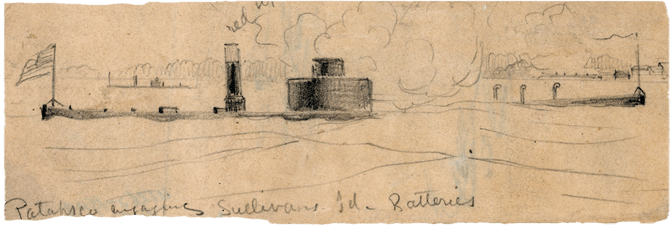

As Federal land forces aimed for the political head of the Confederacy at Richmond, the combined naval and land forces struggled to pierce the heart at Charleston, oftentimes referred to as the “Cradle of Secession”. Ultimately, Confederate steadfastness and ingenuity, along with waxing and waning Union military and political objectives in regards to taking Charleston, resulted in a stalemate between the two combatants. A dead lock only broken by the flanking march through South Carolina by Federal forces under General William T. Sherman. Federal army and naval commanders devised a series of feints and actions along the coastline to assist Sherman in covering his true intentions from Confederate military authorities. The navy assisted by launching a series of incursions up the tidal rivers between Port Royal Sound and Charleston Harbor, and north at Bull’s Bay. The ironclads also opened a heavy fire on Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, and were alerted to possible Confederate attempts to abandon the harbor and city. On the evening of 17 April 1865, Confederate forces kept up limited firing from their outer defenses to cover their retreat. Information from deserters, along with the outbreak of fires in the city, and tremendous explosions caused by scuttling the ironclads provided confirmation that a retreat was in effect. Finally, on the morning of 18 February, Union naval forces pushed their way into Charleston, although mindful of torpedoes and other obstructions which had recently claimed the monitor USS Patapsco a month previous, and planted the United States flag over the abandoned works on Sullivan’s Island, Mt. Pleasant, Charleston, and most significantly, on the shapeless ruins of Fort Sumter.

United States flag flying over Fort Sumter in 1865

Post War Charleston

Following the war, Charleston once again languished as a backwater port with the collapse of its agricultural mainstay—rice, once dependent on cultivation by a now freed labor source. The discovery in the late 1860s of phosphate, used as an agricultural fertilizer, in nearby rivers and land deposits stimulated the economic rebirth of the city. Increased port activity created a need for a number of harbor improvements: dredging ship channels, removing navigational hazards—primarily Civil War-era wrecks, and the building of two stone jetties at the entrance to Charleston Harbor. A natural calamity, the Charleston Earthquake of 1886, once again threw the city into ruins. Despite the setback, the city recovered and by the turn-of-the century harbor improvements and better support infrastructure, along with local political maneuvering, caused the recently created navy base in Port Royal Sound to relocate to North Charleston in 1901. The base remained an important naval asset, building many vessels during World War II, and an economic engine in Charleston until its phased closure by the Defense Base and Realignment Commission in the 1990s. Today the old base is flourishing under civilian enterprises including ship refitting and repairs, leased dock space, light industry, and home to the conservation of H.L. Hunley since its recovery in 2000.

Presently, Charleston is one of the busiest ports in the United States, primarily centered on container ships bringing in diverse products and goods, ROROs (Roll-on/Roll-off ships) carrying foreign cars and other vehicles and machinery, and bulk freighters carrying kaolin and other commodities. Tourism focused on the cultural and natural resources in the region provides another important economic stimulus in Charleston. Historical attractions center on the legacy of plantations, like Middleton Place and Boone Hall, and antebellum planter homes in the city, and especially important, the remains of Fort Sumter in the harbor. Natural resources include seafood obtained by local watermen and by sport fishing, and the low country landscape of tidal marshes, protected coastal waters, and the beaches.

Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield Submerged Cultural Resources

Concluding four years of defending, blockading, and assaulting with various implements of war, both sides of the conflict left an array of cultural features on the battlefield. Unlike many battlefields that may last one day or several days leaving few traces, the siege of Charleston Harbor lasted for four years with a plethora of evidence of the intensity of the fighting. On the Confederate side, the scattered remnants of the ironclads CSS Chicora and Palmetto State scuttled during the withdrawal from the city, along with auxiliary steamers, such as the Manigault, lie on the harbor floor. Several land batteries now lay inundated under harbor waters, most notably Battery Wagner and Fort Ripley. Prior to the outbreak of the war, Confederate forces sank four block ships at the bar of the Main Ship Channel to prevent Federal warships and supply steamers from entering to aid in the relief of the besieged Fort Sumter. Other obstructions developed as the siege continued including a series of log booms stretching across the harbor entrance, and several sets of frame torpedoes in various channel locations throughout the harbor. Evidence of the floating log-booms may not exist; however, piling stumps may indicate the positions of the row obstructions A number of ill-fated blockade runner’s, both underwater and now under the beach, rest off Fort Moultrie, as well as along the northern approach into the harbor—Maffit’s (Beach) Channel. The remains of the Confederate submarine, H.L. Hunley, once lay hidden on the bottom off Charleston Harbor near its victim, USS Housatonic. After the submarine's discovery (1995) and recovery (2000) it now resides in a conservation tank undergoing preservation, eventually slated for display at a purpose built museum in North Charleston.

On the Federal side, a number of vessels and other relicts provide testimony to the Union attempt to take the city. In an attempt to close the harbor to blockade runners, 29 ex-New England whaling and merchant vessels were sunk at the two main channels and quickly consumed by the shifting sediments. Three ironclads, two the victims of enemy actions (USS Patapsco and Keokuk), and the other from foundering (USS Weehawken), rest on the harbor floor. Another remnant of the ironclad fleet, an anti-torpedo raft known as the “Devil” and used by Weehawken, reportedly resides in the marsh behind Morris Island. The first victim of a combat submarine, USS Housatonic, lies buried under several feet of overburden five miles offshore. There are also several Federal batteries, the “Swamp Angel”, with portions remaining visible in the marsh, and Battery Shaw and the Surf Battery, both of which potentially exist, but are now inundated. Research and field operations undertaken to identify these known and potential features from both sides of the conflict served to develop a more complete understanding of the battlefield to aid in the interpretation and preservation of these Civil War resources.

Archaeological Investigations

From 2009 to 2011, the MRD conducted several forays onto the naval battlefield to conduct marine and terrestrial remote sensing operations to detect previously-located and unknown archaeological resources related to the Civil War. These sites included several Union ironclads and a number of Confederate blockade runners, the 7 April 1863 ironclad battleground, and now submerged fortifications and obstructions inside the harbor and along Morris Island. The following section illustrates a few of the areas and cultural resources visited by the MRD in archaeologically-documenting the naval battlefield.

Jim Spirek and Joseph Beatty retrieve magnetometer from Charleston Harbor

First and Second Stone Fleets

The enforcement of the blockade was the primary responsibility of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron (SABS) off Charleston, and throughout its territory along the Atlantic coastline from South Carolina to Florida. The arrival of USS Niagara on 14 May 1861 to enforce the blockade signaled the first phase of naval operations at Charleston Harbor. Stationed off the bar of the Main Ship Channel, other blockading vessels began arriving throughout the next months and subsequent years, taking up stations at the other channel entrances to the harbor, namely Lawford, Swash, North, and Maffitt’s/Beach Channel. Acknowledging the limited number of vessels to enforce the blockade, to perform reconnaissance missions, and to participate in joint operations with the army, Rear-Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont, commander of the SABS, followed a suggestion of the Union Blockade Strategy Board by blocking the two main channels into Charleston Harbor, Main Ship and Maffitt’s/Beach, with two stone fleets.

In mid-October, Union naval purchasing agents purchased approximately 45 ex-whaling and merchant vessels, outfitted them with sea cocks to let water in, and loaded them with granite and fieldstones. The vessels purchased for the stone fleets were an assortment of old sailing, mostly whaling ships including Corea, originally an armed British transport ship captured during the Revolutionary War, Tenedos built in 1806 and mentioned in Herman Melville’s poem, The Stone Fleet (1861), a lament about the vessels of the stone fleet, and Garland, a privateer before becoming a whaler. Two separate divisions, numbering 25 and 20, of the vessels arrived off Port Royal and Savannah in early December 1861. From 17-21 December 1861 the Union navy sank sixteen vessels, reportedly placed in a checkered or indented fashion, at the Bar of the Main Ship Channel. The hulks were intended to lie as much as possible across the direction of the channel, and in several lines apart to overlie each other to prevent a direct line through them. The masts were cut down, and anything of possible Confederate use was stripped from the hulks. One of the ships, the ex-whaler Robin Hood, with masts standing proud, was set afire. By mid-February 1862, Confederate forces found large sections of the hulks washed ashore. From 20 to 26 January 1862, thirteen vessels were sunk as part of the Second Stone Fleet to obstruct the entrance to Maffitt's/Beach Channel, with one escaped outlier between Rattlesnake Shoal and Dewees Inlet Shoal due to a gale.

Union navy sinking ex-whaling and merchant vessels at Main Ship Channel

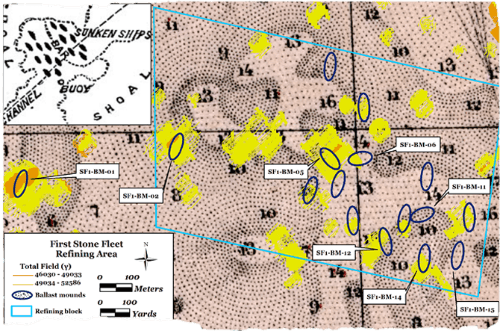

From that point on to the present, the general supposition was that the stone fleet vessels simply dissolved and disappeared into the sand. As part of the grant to document the battlefield, MRD wanted to determine where the fleets rested and to resolve whether they were buried or not. In an effort to locate the remains of the First and Second Stone Fleets, MRD consulted historical documents and generated a georeferenced 1858 harbor map that was overlaid modern nautical charts to begin planning the survey. A georeferenced 1858 chart provided a location for the bar to create the initial survey blocks for the First Stone Fleet. The Federal account of sinking the vessels near Rattlesnake Shoals and the Confederate account that they were scuttled to the west of the shoals at the entrance to Maffitt’s/Beach Channel helped to situate the Second Stone Fleet survey block. The proximity of the wrecks of the blockade runners Georgiana, Mary Bowers, and Constance sunk while evading the blockaders and sunken obstructions by steering for the beach route closer to Sullivan’s Island, lent empirical support to our placement of the survey block. Throwing an electronic cast net over the two surveys detected the remains of the First Stone Fleet and in the Second Stone Fleet survey area four rock-laden scows presumed associated with building the Charleston Harbor Jetties from 1878 to 1895.

At the First Stone Fleet area, the magnetometer detected a grouping of magnetic anomalies and subsequent side scan sonar investigations confirmed the presence of approximately sixteen ballast mounds. MRD underwater archaeologists and volunteers dove on the sites and noted the presence of small to medium-sized rocks encrusted in sediment and marine growth, copper-alloy fasteners, wood structure, and miscellaneous components, including a copper-alloy gudgeon. An illustration showing the sunken positions of the Stone Fleet was located in the New York Herald’s 23 December 1861 edition. The illustration shows the arrangement of the vessels in five lines and staggered and broadsides to the channel. The spatial distribution of the detected shipwrecks by MRD, however, looks a bit more disorganized than the documentary accounts proclaim. One wreck, an outlier to the west of the main group of ballast mounds, was upon inspection found to be more modern in nature, and not connected to the stone fleet. Therefore, one additional ballast mound remains elusive and will require additional survey to locate.

Sonogram of ballast mound detected in First Stone Fleet survey area

First Stone Fleet survey area showing magnetics and distribution of ballast mounds

At the Second Stone Fleet survey area, one uncharted wreck site was discovered by the magnetometer and subsequently confirmed by sonar. The sonar image showed a wreck containing large rocks. Just to the northeast of the survey block, modern nautical charts marked several wrecks and obstructions. In an effort to determine any relationship to the stone fleet, MRD ran side scan sonar over the sites and detected three wreck sites also bearing large rocks as the first site. MRD archaeologists and volunteers dove on the sites and noted the presence of huge stones with some bearing quarrying marks, copper-alloy fasteners, similar windlass or capstan components, and large iron structural elements. Based on the size of the boulders, evidence of quarrying, and proximity to each other, MRD believes these were lighters or scows used to transport rocks to build the Charleston Harbor jetties from 1878 to 1895. These wrecks mostly likely fell victim to one of the hurricanes that struck the area as the jetties were being built. Historical research of Charleston newspapers during this time period found a News and Courier article on damages sustained during the hurricane of 25 August 1885 included the sinking of four lighters loaded with stone by Howlett & Company, the contractors for the jetties. Archaeological evidence suggests that these rock-laden wrecks represent the remains of these lighters from the private contractor’s fleet. Investigating the shoreline in front Fort Moultrie, which had been shored up with rocks during the 1870s reveals stones with similar quarrying patterns as those found on the wrecks. More research is needed to solidify the identity of these wrecks and their connection with the jetty project.

Bent over copper-alloy fasteners in stern at stone fleet vessel

Georgiana & Mary Bowers Shipwreck Site

The Scottish-built blockade runner Georgiana was a single screw iron-hull vessel that measured 205 feet in length, 25 feet in width, 14 feet in draft, and 519 tons burthen. En route to Charleston on its maiden voyage, the vessel stopped in Nassau, Bahamas, and loaded medicines, dry goods, and war material. On the night of 18 March 1863, while slipping between a schooner and steamer off Dewees Inlet, Federal blockaders spotted the blockade runner in Maffitt’s Channel and opened a heavy fire that crippled the vessel. According to reports, the captain had surrendered the vessel, but still endeavored to get to deeper water to escape. Finding the rudder head disabled, the vessel was instead driven into shallow waters approximately ¾-to-1 mile offshore of Long Island (Isle of Palms). Before abandoning the ship, the crew damaged all pipes to flood the hold, and then all those on board escaped in the boats to Long Island. Inspecting the vessel, Union sailors found several Whitworth and Blakely field artillery pieces and a large quantity of ammunition. Hopelessly stuck on the shoals, the Union navy set the vessel on fire with several explosions occurring as supposed gun powder ignited, causing the masts and rigging to fall. Confederate gunners at Battery Marshall opened fired on two Union launches, approximately 3.5-4 miles away, as they departed the wreck. Reports in the Charleston Courier state that the captain of the vessel and several soldiers later went to investigate the wreck but found several blockaders surrounding the wreck. Noticing the men on the beach, the Union ships opened fire and riddled the wreck, extinguishing Confederate hopes of salvaging the sunken vessel. Over the following days, Union crews salvaged various items from the wreck including Enfield rifles, bayonets, battle axes, sabers and other sundry goods.

On the night of 31 August 1864, Mary Bowers, a Scottish-built blockade runner, endeavoring to enter Charleston Harbor struck and stuck on the remains of Georgiana. The 226 feet long, 25 feet wide, 10.5 foot draft, 750-ton side-wheel steamer had made several blockading ventures prior to sinking off Long Island. Recently departed from Bermuda, the vessel carried primarily coal in the bunkers, hold, and on deck. The collision rendered a large opening in the hull’s bottom causing the steamer to sink in a few moments. The Union blockaders only discovered the shipwreck at daylight. Investigating the unknown shipwreck, Union sailors found a 16-year old boy aboard who told them he knew of no cargo other than coal, and that the steamer was to leave laden with cotton bound for Halifax, Canada. Mary Bower’s officers, crew, and passengers had abandoned the wreck. The sailors removed several items from the shipwreck including a bell, binnacle, and several kedge anchors.

The two sites were rediscovered in 1968 by E. Lee Spence, a local Charleston diver, who enlisted the aid of a shrimper to help him find the two blockade runners. Spence and a group of investors subsequently formed Shipwrecks, Incorporated to salvage the Georgiana and Mary Bowers wreck site. The finding and ensuing desire to salvage the wrecks spurred the first South Carolina legislation aimed at managing historic shipwrecks in state waters. The company obtained the first salvage license administered by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in 1969, which agreed on a division of the artifacts: 25% for the state and 75% for the salvors. The salvors found sections of Georgiana’s hull standing over 2.7 m (9 ft) off the seafloor. Under the license, the company recovered numerous relics from the sites including Enfield rifles, bullets, Blakely shells, glass buttons, brass pins, and a variety of ceramics. They also recovered one Whitworth gun under the hull of Mary Bowers which rested atop Georgiana. Over the years, sport divers licensed under SCIAA’s Hobby Diver program began visiting the site and recovered numerous artifacts including a number of Blakely shells, hundreds of shirt or collar pins, and thousands of buttons.

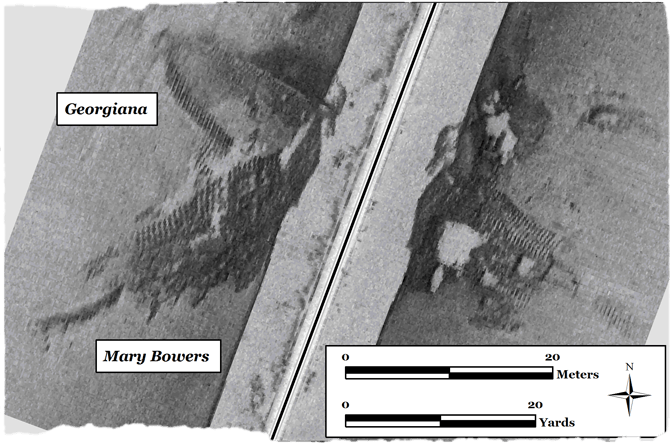

Initial MRD remote sensing investigation of the remains occurred on 8 August 2001 as part of the Naval Wreck Survey using funds from a Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program grant administered by the Naval History and Heritage Command. The remains of the vessels are approximately 1.6 km (1 mile) offshore of Isle of Palms. The shipwreck complex is marked on current NOAA nautical charts. The magnetometer detected a large complex magnetic anomaly and the sonar revealed the criss-cross pattern of the two iron-hulled shipwrecks. The longitudinal axis of Georgiana runs northwest to southeast, while Mary Bowers lies along a northeast to southwest axis. The intersection of the wrecks structure is confused, but their bow and stern areas are identifiable. Georgiana’s bow is the northwest end, and Mary Bower’s bow is the southwest end. The sonograms also revealed the frames of each vessel, along with a couple of boilers.

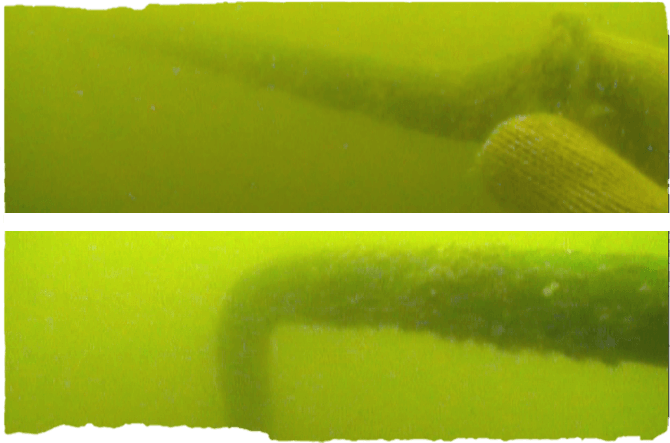

Sonogram of the wrecked blockade runners Georgiana & Mary Bowers

On 30 March and 1 April 2010, MRD archaeologists and volunteers dove on the remains of the two wrecked blockade runners. The objectives of the dives were to examine and to obtain underwater video of the wrecks. Depth of water was about 20 ft (6.0 m). Visibility at the bottom near the bows of the wrecks was poor, several inches at best, due to a constant surge and entrapment of fine sediments in this area. The forward area of both wrecks protruded above the bottom about 2-3 ft (0.6-0.9 m) Moving to the higher reaches of the wrecks, that is the boilers and the amidships starboard hull section of Georgiana, both of which ascended to a height of over 10 ft (3.0 m) above the bottom, improved visibility significantly. Inside the wreck, frames of both vessels were evident, with frame spacing of approximately 1.6 ft (0.5 m) in Georgiana and 2 ft (0.6 m) in Mary Bowers. At the overlap between the two wrecks, the Mary Bowers hull rested about 4 ft (1.2 m) or so above the bottom of Georgiana’s interior. No artifacts were encountered during the dives.

These two wrecked blockade runners attest to the presence of the Union blockade in this area of the battlefield. Their attempts to evade the blockaders to the north and to hug the friendly shore fell afoul of the dangers of this route, namely shallow waters, although Georgiana’s actions were precipitated by effective cannon fire. As noted above concerning the Second Stone Fleet, while the remnants of the stone fleet were not found, the occurrence of these two shipwrecks, along with the nearby wrecked blockade runner Constance, at this location supports the belief that they are close by. And while the Second Stone Fleet effectiveness as a deterrent to using the Maffitt’s/Beach Channel to enter Charleston Harbor may have been marginal, the presence of the sunken vessels along with the floating vessels, made any voyage into Charleston Harbor potentially disastrous.

Patapsco

Launched in Wilmington, Delaware on 27 September 1862, the 1,875-ton single-turreted ironclad USS Patapsco was a Passaic-class monitor. The monitor had an overall length of 241 feet, overall beam of 46 feet, depth of 11.1 feet, and a draft of 11.1 feet. Patapsco was originally armed with a 15-inch smoothbore cannon and a 150-pounder Parrott rifle. In October of 1864, two 12-pounders were added to the armament as deck guns to assist in its blockading duties at the entrance to Charleston Harbor. The vessel was commissioned on 2 January 1863, commanded by Daniel Ammen, and assigned to the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron (SABS).

As part of the blockading forces of the SABS, the monitor participated in the bombardment Fort McAllister near Savannah, Georgia, on the Ogeechee River in early March 1863. On 7 April 1863, at the much anticipated naval attack on Charleston Harbor, Patapsco was the fourth monitor in line. Patapsco began receiving the concentrated fire of the Confederate batteries and forts at the throat of the harbor and sustained several heavy blows to the turret. Inspection of the monitor after the battle determined that 47 projectiles had struck the vessel, especially injuring the smokestack. Following the attack, the monitor assisted in the combined operations to take Morris Island, especially concentrating its firepower on Battery Wagner. Along with USS New Ironsides and the other monitors, Patapsco periodically ventured off Cummings Point, Morris Island to engage Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie and the other batteries on Sullivan's Island. An important role of the monitors after the fall of Morris Island in the fall of 1863 was the enforcement of the blockade. Stationed off Cummings Point, the monitors formed the inside blockade to thwart the entrance and exit of blockade runners at the throat of the harbor.

Monitor USS Patapsco firing on Fort Moultrie

On the night of 15 January 1865, Patapsco was the lead picket monitor and tasked to cover scout and picket boats that were sweeping the channel for obstructions and torpedoes. Accompanied by an array of launches and tugs, the monitor floated into the harbor on a flood tide up to a line between Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie. Then the flotilla steamed or were towed back out towards the harbor entrance. The monitor kept its bow pointed out to sea as it drifted stern-first towards the inner harbor. They did this maneuver three times. On the third trip, and despite the precautions of deploying netting around the monitor and having nearby vessels dragging for torpedoes, Patapsco hit a torpedo and sank in less than a minute. The captain and those standing on the deck and turret survived, numbering 43 crewmembers, while those below decks, except three, totaling 62 perished. Apparently the explosion occurred at or near the port side ward room, or about 30 feet from the bow. Despite starting the pumps, Patapsco’s forward area quickly filled with water and the order to abandon ship was given. The vessel went down bow first, throwing the stern high in the air for an instant before going under, with only the smokestack projecting out of the water. Captain Stephen Quackenbush stated that everybody believed the torpedoes were positioned further into the harbor, and that the crew was not in jeopardy by these maneuvers. A drenched survivor reportedly remarked, “We were told to dredge for torpedoes, and nobody need cry because we found one”. After the abandonment of Charleston, Union navy divers recovered thirteen bodies of the victims drowned at the time of the sinking of the monitor Patapsco. The bodies were buried on James Island.

In 1870, the Monitor Wrecking Company from New York City was awarded a contract by the US Treasury Department to salvage Patapsco and other shipwrecks in the harbor. By the summer of 1870, the company had successfully raised portions of the monitor. A survey of Charleston Harbor in the early 1870s was conducted by Captain William Ludlow, US Army Corps of Engineers. Ludlow found the wreck of Patapsco partially blasted by the wreckers with 15 feet of water over it. A subsequent salvage contract with Benjamin Maillefert a year later ordered a depth of 25 feet mean low water over the wreck of the monitor. Maillefert was to receive the proceeds from auctioning the salvaged materials from the monitor. At the close of the fiscal year 1871-1872, salvage operations had reduced the wreck to a depth of 19 feet. When Maillefert began operations, he reported that the pilothouse and the deck over the engine-house had been removed and the turret partially turned over by wreckers prior to his operations. During the operations to break up Patapsco, Maillefert forwarded recovered human bones to the Army where they were buried at Fort Moultrie. A newspaper article reported on Maillefert’s operations and described his lighter discharging a load of sheathing plates, huge bars, cranks, cogs, and other miscellaneous items. There was also a section of turret about 10 feet by 5 feet and twelve inches thick. The section bore the indentations of the Confederate projectiles. Another component raised was the bow consisting of oak about five feet thick and covered with six inches of iron sheathing.

Initial MRD remote sensing investigation of the remains occurred in 2001 using funds from a Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program grant administered by the Naval History and Heritage Command. Remote sensing operations on Patapsco were conducted on 21- 22 February 2001. A significant magnetic anomaly was detected by the magnetometer and sonar imaged the wreck of the monitor which lay in a NE-SW axis. As part of the ABPP project, diving was planned on the remains of the ironclad to determine the bow and stern, and other identifiable features of the shipwreck. From 13-17 April 2009, MRD archaeologists and volunteers, and assisted by the South Carolina Aquarium, conducted reconnaissance dives to meet our objective of better understanding the remaining structure of the ironclad. Visibility during this time frame ranged from several inches with lights at the beginning to several feet by the end of diving operations. While the current was swift at the surface and in the water column, once inside the wreck area it became negligible. Depth of water ranged depending on the tide from 8.5-9.7 m (28-32 ft).

Sonogram of wreckage of Patapsco

Examination of the wreck provided a great deal of information on the remaining fabric of the ironclad. The forward most area, or southeast end, is the bow of the wreck, and has a section of hull protruding approximately a meter (3 ft) from the bottom along the port side. This area of the hull was the chain locker. Moving aft from this point, several 15-inch cannonballs were found slightly exposed in the sediments. The beams in this area of the wreck are the remains of the berth deck. They are comprised of iron beams 1.3 cm (1/2 in) thick and 1.2 m (48 in) high. These would have originally supported the wooden flooring for the berth deck. Moving through this area was like trying to do underwater hurdling—but rather than jumping, cautiously climbing over one floor and landing in the cavity between two of them, and then proceeding this way until reaching the dredge pipe amidships. Bottom sediment and disarticulated iron structure filled in the cavities here and there and covered the hold deck below the berth deck. Along the southwestern edge of this area was an exposed pipe, which was interpreted as a ventilation tube based on the plans. Along the northeastern periphery of this area was a pile of disarticulated iron components that raised a couple of meters (6 ft) or so into the water column. Based on the ship’s plan, the dredge pipe spans the area where the machinery to turn the turret was located. Where the dredge pipe pierces the port side of the hull, there is a substantial section of hull that curves down into the sediments. Just aft of this area, a large, twisted piece of metal plating protruded about 2 m (6 ft) in the water column. This might be related to a portion of the turret compartment bulkhead. From this point on, the archaeologists encountered various disarticulated iron components, mostly small in nature including a small section of framing. This area of the wreck is where a coal bunker was located, so this piece may relate to the bulkhead fabric. Time limited further investigation of the wreck beyond this point to determine if the propeller or any integral stern structure existed.

As mentioned above, the wreck lies with its bow facing out to sea while the stern points in to the harbor. This corresponds with the last actions of the ironclad as it floated stern-first to Charleston on the flood tide and then reaching the Confederate obstructions steamed back towards Cummings Point, while clearing torpedoes. Upon striking the torpedo, the ironclad sank rapidly to the bottom with no turning or twisting motion. The identification of the berth deck confirms that the south end is the bow of Patapsco, and the area beyond the dredge pipe as the stern, emptied of the machinery and boilers which were salvaged in the 1870s. From a profile view, there are portions of the hull plating that extend above the berth deck, primarily along the port side, and it is estimated that approximately 1.6-1.9 m (5-6 ft) from the keel to the extant hull plating of the wreck exists in the forward area of the ironclad. Direct observations in the stern area of the wreck was limited, but based on the plans, it is estimated that approximately 0.3-0.6 m (1-2 ft) of depth exists from the keel to extant hull, although in some areas there are sections of the port hull plating extending beyond the bottom. Salvage operations by Benjamin Maillefert and the Monitor Wrecking Company were thorough in recovering the main iron components of the wreck—turret, boilers, machinery, armor belt, and hull decks and plates, leaving little behind. Besides the remaining ship’s structure, a couple of 15-inch cannonballs, no personal artifacts were observed in the wreckage. Despite the severe nature of the salvage operations, the remains of Patapsco offer a rare glimpse at the main offensive weapon used by the Union navy to enforce the blockade and to challenge the Confederate gauntlet at Charleston Harbor.

Fort Ripley

In early 1862, work commenced on building a fixed battery on the Middle Ground Shoal, located between Castle Pinckney and Fort Johnson. Called Battery or Fort Ripley, as well as the Middle Ground Battery, the fort was designed to support Fort Moultrie in the event of a bombardment of that fort, as well as a strong addition to the defense of the city. The four-squared work rested on timber caissons, ballasted with the rubbish from the 11-12 December 1861 fire in the city, in a water depth of eight feet. General Robert E. Lee, then in command of Charleston defenses, suggested casemating the fort with heavy timber and railroad iron to strengthen the work, although the engineers did not consider the work shot proof. By July the fort reportedly had five guns installed in the defensive structure. A report in 1864 listed Fort Ripley having one 8-inch Columbiad and one 10-inch Columbiad. Positioned about 600-700 yards in front of the battery was a double row of pile obstructions stretching due north from the Middle Ground and across the Castle Pinckney/Folly Island Channel for half a mile. Despite its interior position, Federal batteries at Cummings Point occasionally tossed a few shells at Fort Ripley. After the abandonment of Charleston by Confederate forces, Union army and navy units began raising the United States flags over the various military installations, including Fort Ripley, where an Union officer remarked that the guns were in good order, and that one Quaker gun was mounted bearing southeast.

Drawing of Fort Ripley

Today the remains of Fort Ripley are marked by a navigation sign warning of the danger of the rock obstruction. During low tide, broken bricks and ballast stones protrude above the surface to reveal the location of the fort. On 25 March 2009, MRD conducted a magnetometer and side-scan sonar survey around the battery. The electronic instruments detected a number of magnetic and acoustic anomalies around the site. There is a heavy magnetic concentration at the mound, along with a number of large, isolated anomalies in the general vicinity. Acoustic data corresponding with magnetic anomalies revealed several indistinct iron objects. Sonar data revealed the mound measures at the base about 37 m (121 ft) from east to west, and 39 m (127 ft) from north to south. On the western periphery the water at low tide was approximately 12 m (40 ft) deep, while approximately 1.2 m (4 ft) deep on the eastern side.

Brick rubble exposed during low tide at Fort Ripley with Charleston in background

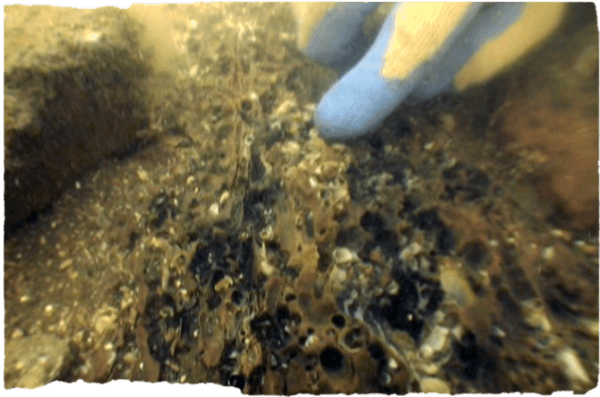

In an effort to identify the sources of the magnetic anomalies and to determine what else remained of the fort, archaeologists dove at the site on 23 April 2010. During slack low tide, with exceptionally clear water down to 12 m (40 ft), the archaeologists circumnavigated the fort, finding the base composed primarily of ballast rocks, and further up an admixture of rocks and bricks. Several iron bars were found accounting for some of the magnetic anomalies detected during the remotes sensing survey. Moving up the summit, careful examination revealed the presence of several severely eroded and teredo navalis-wormhole riddled timbers embedded between the rock and brick matrix. The timbers measured approximately 20.3 cm (8 in) in width, and lengths indeterminable due to their disappearance underneath the rock and brick overburden. These timbers probably represent the bedding frames of the caisson used to secure the fort to its underwater foundation. Nothing else was found on the reconnaissance dive to suggest its past use as an inner harbor defensive structure.

Eroded wood associated with the crib foundation of Fort Ripley

KOCOA Analysis and Defining Features

A modern military analysis scheme called KOCOA, a method to understanding the natural, cultural, and military features of the landscape and their effect on a battle, provided a framework by which to analyze and interpret the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield. Developed by military experts to prepare for battle and to study and analyze the aftermath of one, the KOCOA system considers these components of the landscape crucial to understanding a battlefield: Key terrain, Observation and fields of fire, Concealment and cover, Obstacles to movement, and Avenues of approach and retreat. The NPS advocates applying the KOCOA scheme to analyze historic battlefields since first using it to re-interpret the Battle of Gettysburg in early 2000. While the acronym is modern, the basic underlying military tenets are ages old. This method is mainly applied to analyzing terrain related to land battles, however, the suitability of this scheme to naval purposes is particularly useful in understanding a battle fought in coastal waters. Shoals and channels in shallow waters off the coasts act as impediments to fleets, in a manner similar to hills and valleys that constrict the movement of armies.

Battlefields are generally thought of as engagements lasting for several hours or days at most—and fought on land. The siege of Charleston Harbor, however, spanned four years from the Federal surrender of Fort Sumter in 1861 to the Confederate abandonment of Fort Sumter in 1865—and was fought on land and sea. Combined Union army and naval forces attempted to wrest control from the steadfast Confederate defenders to no avail. Only the anticipated arrival of Sherman from the rear sprung the harbor open to Union forces. During those four years a number of naval and combined actions occurred as each antagonist strove to meet their respective military objectives. Major battle events included the Confederate ironclad sortie against the blockading fleet on 31 January 1863, the 7 April 1863 Union ironclad attack on Fort Sumter, the Union capture of Morris Island and reduction of Fort Sumter through combined operations, and attacks by Confederate semi-submersibles and a submarine on the blockading fleet. If one were to compress these actions spanning four years into a day and on a single map, it would clearly resemble a traditional battlefield with advances, counter-thrusts, skirmishes, etc., all constrained by the natural, cultural, and military engineering features present in this maritime landscape. While these actions occur in temporally isolated incidents, they are still spatially constrained by the same environmental features.

\

\

Routes of naval battle actions fought in Charleston Harbor

Each of the naval actions off Charleston Harbor was fought on the same battleground and therefore exhibit a number of commonalities to each other with few exceptions. Most of the battle episodes were fought at night; in fact all of the Confederate actions were precipitated in the darkness—blockade running and attacks upon the blockaders. The nature of the coastal environment of low barrier islands and the limitless view from the beaches, mastheads, walls of Fort Sumter, and to the horizon during optimal days necessitated a need for the cloak of darkness for surprise attacks. This was especially needed in light of the Confederate spar-torpedo weapon delivery system which required contact with a vessel. Only the Federal ironclad attacks on the Confederate batteries were accomplished in the daylight due to their armor plating, although the obscurity of night was used on occasion. Another important consideration was the states of the tide—ebb or flood. The ebb was the preferred tide of the two Confederate vessels David and H. L. Hunley to assist in the motive power to bring them to the blockaders and then later rely on the flood to withdraw to the safety of the harbor. Most of the larger ship actions took place on the flood to permit these vessels to cross the bar and navigate in the channels, as did blockade runners to lessen the margin of error in navigating the shallow waters. In the case of the 7 April 1863 ironclad attack, the ebb was relied upon to draw a disabled Union warship out of the harbor. The primary avenue of attack and withdrawal was the Main Ship Channel by both combatants. The Confederate ironclads sortied out of the harbor from it, and David and Hunley in hunt of monitors and New Ironsides employed the channel as well. All Union naval attacks on the Confederate fortifications relied on the Main Ship Channel from which to bombard or to transit to the throat of the harbor to engage Fort Sumter and the Sullivan’s Island batteries. The only instance of an offensive action occurring elsewhere is when Hunley used Breach Inlet to attack the north line of the blockade. Maffitt’s/Beach Channel, used as the avenue of withdrawal for the Confederate ironclads, was the primary channel for the blockade runners.

The locations of the Confederate and Union shipwrecks on the battlefield attest to the intensity of fighting occurring at the harbor and exhibit the patterns of the ongoing siege at Charleston. The illustration clearly shows a pattern to the locations of the Union and Confederate shipwrecks. The Union vessels are located to the south of the harbor, reflecting their occupation of Folly Island and Morris Island. The remains of Housatonic beyond the 18-foot-contour indicate its position on the line of wooden blockaders attempting to enforce the blockade. The Stone Fleet locations were both designed to obstruct the two main routes of the harbor. The two clusters of blockade runners clearly reveal the main blockading route into and out of Charleston and attest to the natural and military dangers of navigating that channel. The Ruby wreck seems to contradict the effective closing of the Main Ship Channel by the presence of the monitors and the First Stone Fleet but was in reality just lost in the night that so ably shrouded the vast majority of blockade runners that successfully ran the Union blockade.

Location of shipwrecks on the naval battlefield

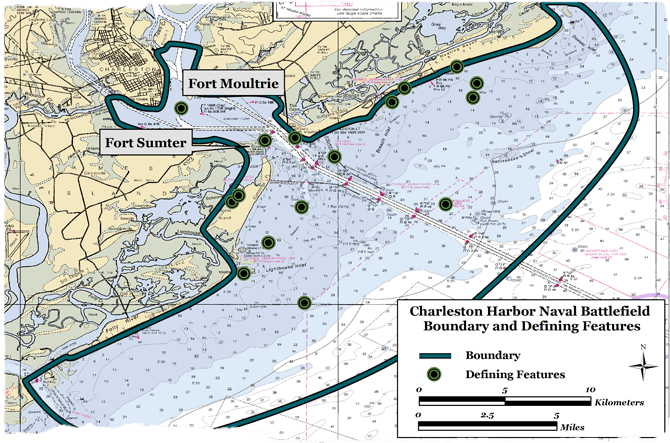

Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield Boundary

The purpose of this project was to delineate the boundary and to identify the defining features of the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield through historical and archaeological documentation. The boundary was defined through examining the historical records that determined the battlefield as comprehended by the combatants stretched along the coastline north from Dewees Inlet to the south at Stono Inlet, east to just beyond the 18-foot contour line, through the throat of the harbor entrance bounded by Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie, and to either side of the city on the Ashley and Cooper Rivers. Within this battlefield the major naval actions occurred, including the Confederate ironclad sortie on 31 January 1863, the 7 April 1863 ironclad assault, the sinking of Housatonic by the H. L. Hunley, and the enforcement of the blockade. The archaeological manifestations of the conflict, wrecked blockade runners, sunken Federal ironclads, the remains of the first successful combat submarine and victim, provide testimony to the battle events that occurred within the boundaries of this battlefield. These remnants of the naval actions were precisely located with DGPS and investigated through electronic means to determine their scope and extent. Visual inspection by underwater archaeologists aided in interpreting the visible features of these sites. Establishing the battlefield boundary and the presence and distribution of the associated archaeological components permitted meeting a corollary objective of the project to determine issues affecting the preservation and protection of the battlefield.

Boundary and core features of the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield

There have been significant physical changes to the naval battlefield, primarily a result of the placement of two jetties to form a more direct channel through the bar to the port. The natural features of the ebb-delta complex consisting of the bar and channels have been completely altered by the construction of the jetties that essentially eradicated the two primary Civil War-era channels into the harbor: Main Ship Channel and Maffitt’s/Beach Channel. The beachfront of the islands of Sullivan’s Island and the south end of the island have accreted seawards, evidenced by the presence of several buried blockade runners. Morris Island, however, has suffered from severe erosion south of the south jetty, with some accretion at Cummings Point. There are still natural, cultural, and military features a participant from the siege would recognize, but the built-up environment has also modified the battlefield with beachfront homes, bridges, and high rises. But one thing does continue, the port of Charleston has rebuilt itself into an important transshipment hub in the southeast, and the sea is still an important front door to the world.

Management Issues

Shipping and tourism play an important part in the economics and quality of life in Charleston. However, these enterprises also put pressure on the local environment which in turn affects the archaeological resources residing in and along the local waters. Increased demands for larger ships to carry more goods require the port to accommodate these new vessels. Under the authority of the US Army Corps of Engineers, harbor maintenance requires constant upkeep and improvement of navigation to provide safe passage. Development along the shorelines of Sullivan’s, Isle of Palms, and Folly Islands, along with the natural tendency of the barrier islands to erode, has prompted beach renourishment using offshore sand borrow sites to protect public and private investment along the beachfront. Maintenance dredging, channel widening, and beach renourishment all have the potential to impact the cultural legacy of not only Civil War related materials, but also from other historical periods as well. This project aims to mitigate these varied threats by accurately locating submerged cultural resources affiliated with the naval operations during the siege of Charleston. Additionally, the archaeological remains, combined with historical research, established the core and defining features by which to delineate the boundary of the battlefield. Determining the battlefield boundaries and cultural resources will serve to guide short and long-term management decisions affecting the integrity and preservation of this maritime battlefield.

Conclusion

The historical and archaeological information derived from this project to document the boundary and cultural remnants of Charleston Harbor served not only to illuminate the past, but also the present and future of this important naval battlefield. By delineating the boundary and documenting extant features, managers charged with the preservation of these nationally significant cultural resources can use these findings to interpret and to protect the battlefield. By knowing the natural and cultural locations of these resources in the present, managers may better anticipate looming and distant issues surrounding the preservation of these battlefield vestiges. Two major developmental issues with the potential to impact the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield are navigation improvement and beach renourishment projects. The continuing research, educational, and recreational potential of this naval battlefield requires all interested stakeholders to participate in the preservation of this unique Civil War legacy.

Acknowledgements

The project and report was made possible through an American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) grant administered by the National Park Service (NPS). Additional funding was provided by the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology (SCIAA) at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. A number of institutions and volunteers assisted and supported the project objective of documenting the naval components related to the siege of Charleston Harbor during the American Civil War:

Our sincere thanks go to Kristin McMasters, archaeologist and grant administrator, January Ruck and the other grant administrators that followed in her wake, of the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program in Washington, DC for their assistance in preparing and implementing the grant. We also received material and logistical support from the NPS’s Fort Sumter National Monument unit in Charleston, especially Bob Dodson, director, and Rick Dorrance, along with other personnel.

Much appreciated research assistance was provided by various archivists and support personnel at the National Archives I and II in Washington, DC, and College Park, Maryland, and the South Carolina Historical Society in Charleston.

Special thanks go to the South Carolina Aquarium for providing use of their research vessel under the supervision of Arnold Postell, dive safety officer and aquarist, along with support personnel. The boat served as an additional platform for diving operations on the remains of Patapsco.

Dr. Lee Newsom, Penn State University, provided wood analysis of samples from the reported Weehawken torpedo raft.

A number of volunteers assisted the project during marine remote-sensing and ground-truthing operations: Andrew Ogburn, William Semple, Ted Churchill, Dr. Paul Work, Dr. Scott Harris, and Phillip Jones.

Dr. Jonathan Leader, State Archaeologist, for conducting gradiometer and ground-penetrating work, along with his volunteers, Bonnie Leader, his wife, and Randy Burbage.

A number of internal University of South Carolina administrative units assisted in preparing the initial grant, namely Jeffery Tipton, grant administrator, of Sponsored Awards Management. Margeret Binette and Frenché Brewer of the Office of Media Relations prepared and organized media relations with Charleston news outlets. SCIAA director, Dr. Charles Cobb, and business manager, Susan Lowe, provided grant management guidance and oversight. Dr. Steve Smith, director of Applied Research, supplied insight of the ABPP grant preparation and execution, and research information. Maritime Research Division personnel: Christopher Amer, head, and Lora Holland, Carleton Naylor, Joseph Beatty III, and Ashley Deming greatly assisted in implementing the research and field work aspects of the project; none of which could have been done without them. To them and all the others—thank you for your efforts and assistance in investigating the Charleston Harbor Naval Battlefield.

Related Information

2012. Spirek, James D. "The Archaeology of Civil War Naval Operations at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, 1861-1865." Maritime Research Division. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of South Carolina. Columbia, South Carolina.

2012. Spirek, James D. "The Archaeology of Civil War Naval Operations at Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, 1861-1865." Legacy. Vol. 16, No. 2. November. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. University of South Carolina. Columbia, South Carolina. pp. 4-9.