WGST Student Assistant Emma Philbeck sat down recently with Dr. Allison Marsh to discuss her latest work. During the 2024-25 academic year, Dr. Marsh was the NEH Fellow in residence at the Linda Hall Library for Science, Engineering, and Technology in Kansas City, MO. Her research involved combing through the former library of the United Engineering Society and the publications of the IEEE (Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers), and its predecessor organizations, the IRE (Institute of Radio Engineers) and AIEE (American Institute of Electrical Engineers), to create a database of women who contributed to these professional societies. Professor Marsh is also the Co-Director of the Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society, a center on campus promoting interdisciplinary collaboration among humanists, scientists, engineers, and medical professionals. Before coming to USC, she was Curator and Winton M. Blount Research Chair at the Smithsonian Institution National Postal Museum. Dr. Marsh combines her interests in engineering, history, and museum objects to tell stories of technology through historical artifacts. As a public historian, her main research interests revolve around how the general public comes to understand complex engineering ideas, especially outside the classroom—through museums, documentaries, TV shows, and so on. Her work focuses on gender representation in museums and women in science and technology.

Your area of study is very much rooted in history, artifacts and the past. How does your research intersect with or compliment women's and gender studies?

Electrical engineering has been about 12% women forever, it is an incredibly male-dominated field. Throughout my career I have heard from too many members of the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, which is the professional association for electrical engineers, who have said things like, "Oh, women just aren't interested in electrical engineering. They've never been interested in electrical engineering”. I decided I'd had enough and wanted to go find the women that this rhetoric is actively erasing and tell their stories. I spent all of last year at the Linda Hall Library where I was researching, going page by page through all of the journals of the professional organizations and writing down the names of every single woman who is named, whether that was as a published author, as someone in the acknowledgement, or someone who's mentioned on the side. Now I have a huge database of women that we know existed who were active in the field.

At first I wanted to be an engineering major, and back then you had to finish out your electives before you could declare your major. By the time it came to when you actually got to choose your major, I realized all of my electives had been history, and I decided "oh, I should just get a history major". So, I double majored in history and engineering, although engineering was definitely my focus, and as a result, my history major is scattered all over the map. After college, I got a job as an engineer and I worked in technical consulting for several years. One day it got to a point where I felt like I was going to throw my laptop through the window. I thought to myself, “Oh my God, I can't do this anymore". I looked at my resume and I was like, "Hey, I've been volunteering in museums since I was 14. I wonder if I can make a go of that?" So I went back to school, got a PhD in the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, and then started working at the Smithsonian Institution as a curator of 3-D objects. My interest in the intersection of history and engineering has always been through the museum field, and it has allowed me to tell stories about the past while explaining complex engineering ideas to a broad audience.

You’ve spent much of your career combing through museums and incredible libraries like the Linda Hall Library for Science, Engineering, and Technology. What has been the most interesting artifact you’ve found or what has had the most impact on you in your search?

Every object, every artifact, and every person that's come across my desk has been my favorite. Every object makes you realize someone actually had to design that, manufacture that, figure out what's the best way to use that, and each one has its own story no matter how mundane or revolutionary it may have been. It's always fun to look at the things that failed and think "what went wrong with that one? Who thought that was a good idea?" And then it's interesting from those failures what became successes. This also applies to people as well in the history of electrical engineering. The most recent story I've really latched onto is that of Mabel McFerran Rockwell, who was the only woman who worked on the power design for the Hoover Dam, and there was no Wikipedia page for her. I thought, “She is the only woman who worked on the design of all of the power systems for the Hoover Dam. Why is she not named anywhere?” I took it upon myself to create a Wikipedia page for her. The more I looked into her, the more amazing she became. Not only did she work on the Hoover dam, but she worked in Southern California on their power distribution, and was actually in charge of it. Then she worked with Hughes Aircraft on welding designs and even worked on the Polaris missile designs. By the end of her life, she thought we had done enough research into weapons and war and decided we needed to really work on peace. In the end, she became a very strong peace advocate. I just love her story as this pioneering woman who did so much with her life and carved her own path in a field that never wanted her to.

Visit her Wikipedia page and learn more about Mabel MacFerran Rockwell here!

You’re in the midst of writing a book for the 150th Anniversary of the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, meant to highlight the ignored women of history. Can you tell me a bit about what that process has been like and what we can expect from the book?

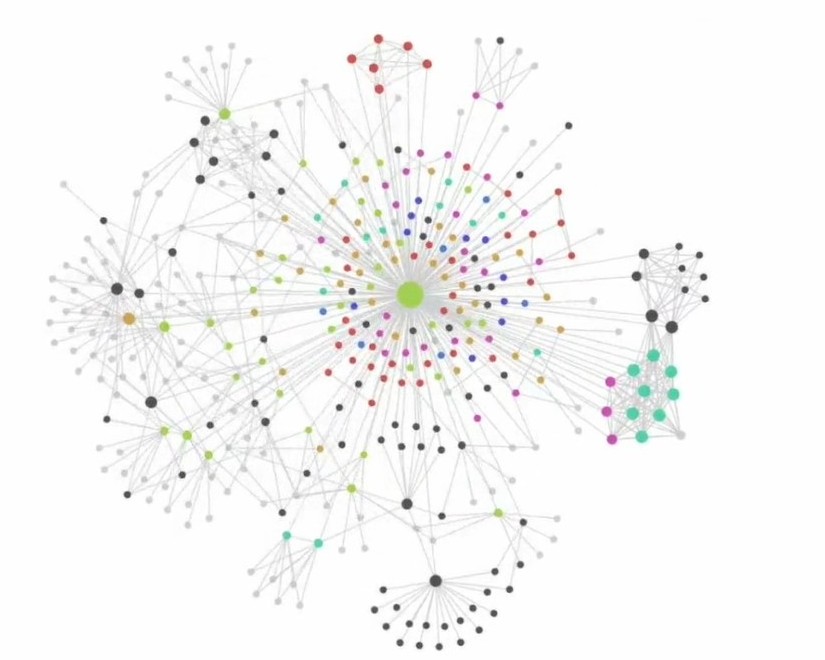

Right now I’m building the foundation of the book, doing research and collecting the biographies and recovering the names of all of these women. I want to know more about who they were and what they did so I started making a database of all of these women where I'm using software to map their network connections. It’s interesting to define what it means to be an engineer, because at the beginning of the profession there were no schools that were teaching electrical engineering--it was a new thing that people were just discovering. So, do you become an engineer through your education? Do you become an engineer through your work experience? Do you become an engineer through your publications, the societies in which you belong or join? I'm thinking about structuring the book along all of those different pathways because women weren't immediately granted access to the educational path. Electrical engineering is a very big umbrella. People who go into it come from computer science, physics, and math. It begs the question, when do you cross that line and when do you become a part of this community? How much is that self-defined? Those are some questions I’m asking at the moment, so I'm a few years away from publication.

As Co-Director of the Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society, can you tell me more about the slogan of the AJI, “community is the method”? What does this mean to you and how does community better the sciences and better ourselves as researchers?

Ann Johnson was a friend and a colleague here at USC. She was a professor who had a joint appointment in history and philosophy. She was a massive proponent of connection and was constantly running across campus communicating with people in chemistry, engineering, etc. She wanted to connect as many people as possible from as many disciplines as possible because she believed to do good research you had to know the full person. You couldn't just know them in their work environment and what their research was about, but you needed to know about their life and you needed to be a friend. She made it a point of bringing like-minded people together, not just in work, but also in social contexts, believing that research grows out of connection and community. When we established the institute, we chAnnled who Ann was as a person. We wanted to share her vision of breaking down intellectual silos that exist across campus and making connections among people, because in the end it's the community who really makes us who we are. So that is where the tagline "community is the method" comes from.

Learn More:

Dr. Marsh also writes the “Past Forward” column for IEEE Spectrum. Each month she chooses a museum object in the history of computer and electrical engineering and spins out an engaging tale. Her subjects have included Japanese housewife Fumiko Minami’s contributions to the invention of the automatic rice cooker, artist Lisa Krohn’s futuristic Cyberdesk, and the history of the hot comb. She also writes and narrates a YouTube series for Spectrum . The first episode is how E. O. Lawrence – Oppenheimer’s BFF (and then not) – took time off after winning the Nobel Prize and working on the Manhattan Project to dabble in inventing color TV.

As the consultant for the hit YouTube series, Crash Course: History of Science, her work has reached more than 22 million viewers. She organized the series around her HIST 108 syllabus and used the videos in her online version of the course. In doing so, she studied content retention from videos versus the traditional textbook. She published the results (which can be found here) with her teaching assistant, Bethany Johnson, and has incorporated the lessons learned into her subsequent online teaching.