The state of South Carolina has a surprisingly rich history of Jewish presence dating back more than three centuries. It's not surprising, then, that the University of South Carolina would have its own history of Jewish life on campus.

TRANSCRIPT

Here’s a quick trivia question for you: Which city in the United States had the largest Jewish population in the early 1800s? This isn’t a trick question, but the answer might surprise you.

Charleston, South Carolina, was home to this country’s largest concentration of Jewish citizens for the first three decades of the 19th century.

In fact, there’s a rich history of Jews in South Carolina that goes back at least 300 hundred years and includes a long list of prominent politicians, business people, artisans and professionals who have helped shape the Palmetto State in myriad ways.

I’m Chris Horn, your host for Remembering the Days, and today we’re tracing the history of Jewish presence at the University of South Carolina, starting in the early 1800s and all the way up to the present.

The story begins with Franklin J. Moses Sr., a Charleston native who was most likely the first Jewish student to graduate from South Carolina College, the precursor of the University of South Carolina. After he earned his degree in 1823 at age 17, Moses studied law, became a lawyer and later a judge and was elected to the state Legislature where he served with distinction. In 1851, he became a trustee at his alma mater, South Carolina College, and also taught as a law professor there. Moses’ crowning achievement was being elected chief justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court in 1868.

Another early Jewish alumnus of South Carolina College was Joseph Lyons, who graduated in 1832. We don’t know a lot about Mr. Lyons except that his father, Isaac, and his older brothers ran a popular oyster saloon at the corner of what is now Main and Gervais Streets in Columbia. It’s been said, perhaps not surprisingly, that many of Lyons’ fellow South Carolina College classmates frequented that establishment in its heyday.

Still another Jewish student, David Camden de Leon, earned his degree from Carolina in 1833 and became a doctor, first for the U.S. Army and later for the Confederate Army when the Civil War broke out.

Now let’s fast forward to 1900 when a man named August Kohn was elected a trustee for the University of South Carolina. Kohn was an 1889 graduate of Carolina who became a journalist for the Charleston News & Courier and was known for his fair and balanced reporting, a notable achievement in that era of highly partisan news coverage.

Kohn’s resume went far beyond journalism, though. He played a prominent role in the founding of the Tree of Life synagogue in Columbia. He also became a highly regarded stock and bond broker and an insurance agent, and he was the real estate developer for several of Columbia’s earliest neighborhoods such as Wales Garden near Five Points.

As a trustee at Carolina, Kohn lobbied the General Assembly for better funding for the university and, on his own dime, he often traveled to New York to solicit funding for Carolina from some of the big philanthropic foundations there.

At Kohn’s suggestion, the Alumni Association started a scholarship fund for needy students, and Kohn himself provided personal loans and outright gifts to students when the scholarship fund ran low. In 1908, Kohn was even championed by newspapers and professors to become USC’s next president, but he demurred. According to his daughter, Helen Kohn Hennig, he did not feel that his alma mater was quite ready to have a Jewish president.

Kohn continued to vigorously serve as a USC trustee until 1924 when he failed to win reelection in the state Legislature. It was around that time that the Ku Klux Klan had risen to prominence in South Carolina and across the nation, and dozens of state legislators were believed to be KKK members or were at least sympathetic to its cause of disenfranchising Blacks and members of the Catholic and Jewish faiths.

Kohn was very disappointed by his defeat as were many of the university’s friends and supporters in the business community and beyond. Yates Snowden, a revered history professor at USC at the time, penned a poem in 1925 about the university’s progress that included these lines honoring one of the university’s most industrious and loyal trustees:

“When you gaze upon our library, That mass of brick and stone,

Oh, add this to your orisons: May God bless August Kohn.”

We’ve talked about the first Jewish students and a prominent Jewish trustee at Carolina. Let’s consider the university’s first Jewish professor, a man named Josiah Morse.

It’s worth noting that Josiah Morse was not his real name. Josiah Moses was born in Richmond, Virginia, and earned a Ph.D. in psychology in the early 1900s. He was also an expert in ancient languages of Greek, Hebrew and Latin, but he was having trouble finding a position as a university professor. To pay the bills he began writing pop psychology articles for magazines under a pen name — Josiah Morse — on topics like “Why men gamble” and “Why children run away from home.”

When he applied at universities using his pen name, Josiah Morse, he started receiving offers for teaching positions, and Morse became a professor at Peabody College of Teachers in Nashville and at the University of Texas. When one of his mentors, Samuel Mitchell, became president at USC, Morse was invited to join the Carolina faculty and so in 1911 became the university’s first Jewish professor.

The occasion was not without incident. When USC professors learned of the new appointment, they voted unanimously to send a delegation to the president to express their outrage that Christian gentlemen would be expected to associate on equal terms with a Jew. USC’s president replied to them: “If you feel sufficiently outraged to resign, I will accept your resignations. Plural.” None of the professors resigned, and in time, Morse became one of the most popular members of the faculty.

He wrote four books on psychology, volunteered as state director of the American Red Cross and devoted his early career to the cause of civil rights. He organized interracial meetings at the university YMCA between USC students and students from Allen and Benedict, the two all-Black colleges in Columbia. He even taught a course on the race problem in the South — quite a daring thing to do back in the Jim Crow era.

Morse became a tireless advocate for Jewish refugee efforts before and during WWII. When he died in 1946, the Gamecock student newspaper published the headline: “USC mourns death of great man.”

We’ll wrap up our timeline of Jewish presence at USC with a look at a Jewish club, which became a fraternity on campus.

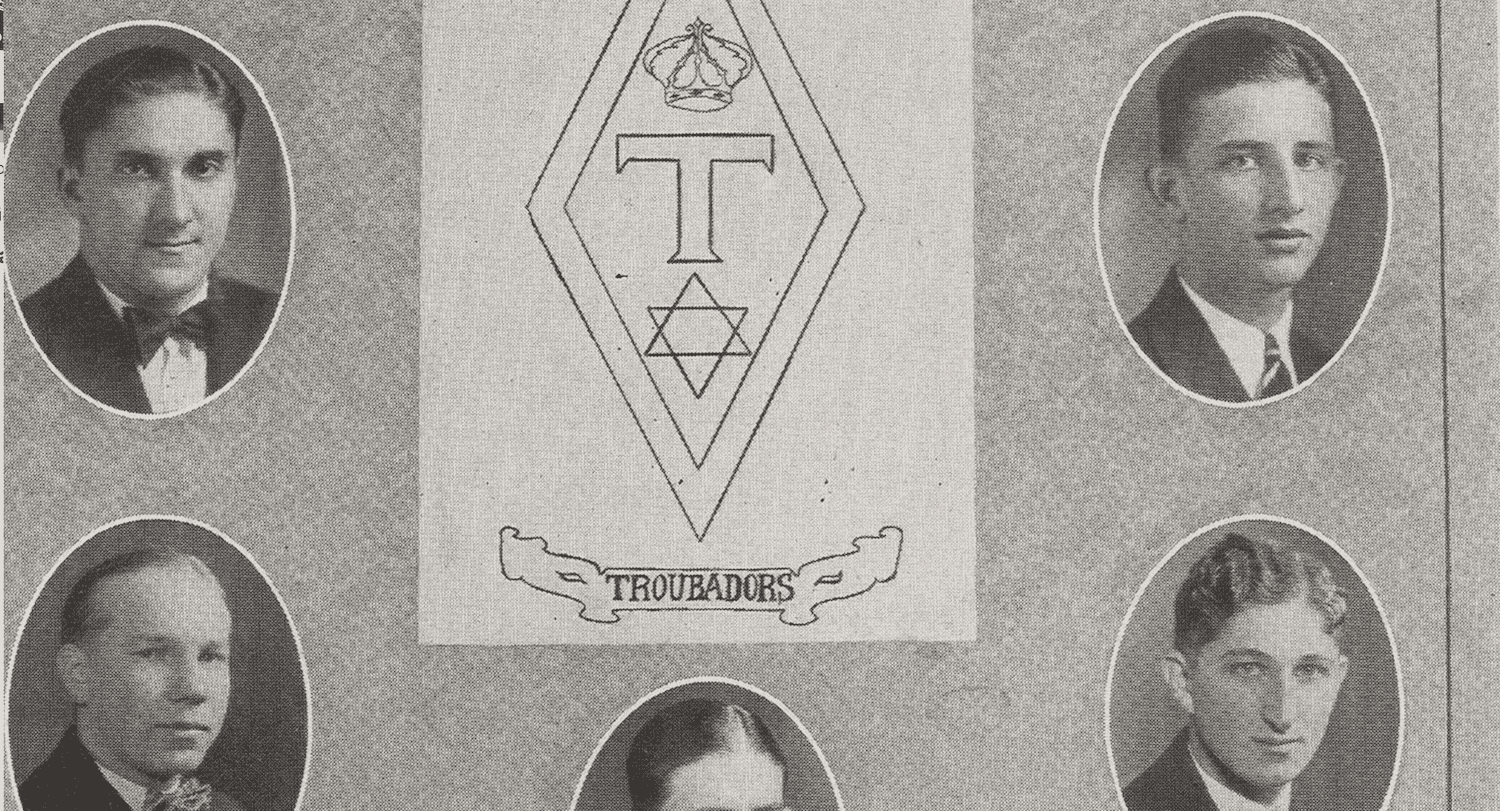

In 1927, an all-male organization called the Troubador Club, whose members were Jewish, appeared at Carolina. The next year, the club morphed into a chapter of Phi Epsilon Pi, a national fraternity that had started in 1904 in New York City. Phi Ep, as it was called, was nondenominational according to its charter but in practice the membership of all of its chapters was predominantly Jewish.

I caught up with Charles Bernstein, a USC alumnus and retired lawyer in Charleston, who was a member of Phi Ep in the late 1940s.

Charles Bernstein: “There were two Jewish fraternities on the campus and two Jewish sororities and. It was understood. There was never any question that if you were Jewish and you were going to be in a fraternity or sorority, that's where you would be. You didn't have any mixing in between. You were Jewish and you expected to associate with the Jewish groups on the campus.

In spite of that self-segregation in fraternities and sororities of Jews and non-Jews back then, Bernstein says there wasn’t any discrimination on campus because of one’s faith.

Charles Bernstein: “I was never aware of any active anti-Semitism in any way, shape or form. We were just all students together.”

Joe Wachter, a USC alumnus and practicing attorney, was a member of Phi Ep in the 1960s. He grew up in Spartanburg, and remembers the fraternity as kind of an extension of the Jewish youth groups that were part of his adolescence in South Carolina.

Joe Wachter: “I immediately joined PHI Ep because I'd grown up with a lot of those guys. We had youth groups all over the state and we met each other from the eighth grade and for socials and basketball events and so on. And so it was just you had some sort of instant friends that you already knew.

"I always thought of Phi Ep as sort of the blue-collar fraternity. They weren't wealthy. Some were, but most weren't. My dad, my father, was a working class guy. There was more of that mentality in that group than I think in a lot of the fraternities.”

Phi Ep disbanded in 1970 and was replaced by Zeta Beta Tau or ZBT, which had started as a Jewish fraternity in New York City in the 1890s.

I talked to Bob Bernstein, Charles’ son, who is also a USC undergraduate and law school alumnus and who was a member of ZBT in the 1970s. He says the fraternity reflected the changing nature of Jewish life on campus, which was becoming far more assimilated with non-Jewish students.

Bob Bernstein: “Well, I mean, we had our fair share of non-Jewish kids from South Carolina or from the South. But yeah, it was probably about 50% Jewish, 45% Northern, maybe 5% otherwise. I met a lot of people. It didn't it really didn't matter to me whether they were Jewish or not. It was just a bunch of good folks.”

Like his dad, Bob says he didn’t encounter any opposition because of his faith, while acknowledging that a lot of native South Carolina students had probably never thought much about Judaism and perhaps had never even met a Jew before coming to USC.

Bob Bernstein: “I kind of kind of melded in and made friends and nobody ever asked what my religion was. Having said that, with the name Bernstein, it's really not too hard to figure out.”

The last stop on our Jewish timeline at USC is rather recent. In 2021, USC was selected as a partner site with the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. No doubt you’re familiar with the story of Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl who perished in the World War II Holocaust.

USC’s Anne Frank Center, one of only four such centers in the world and the only one in North America, contains historic replicas of items from the original Anne Frank House, including the bookcase that the Frank family hid behind for two years before their capture by the Nazis. The center offers guided tours to the public so check it out if you can next time you’re on campus.

That’s all for this episode. Next time we’ll revisit USC’s fateful decision in the 1970s to walk away from its charter membership in the Atlantic Coast Conference and the opportunity that came in the early 1990s to join the Southeastern Conference. That’s on the next episode of Remembering the Days. Until then, I’m Chris Horn. Forever to thee.