Sixty years ago, the University of South Carolina became one of the last major public universities in the American South to open its doors to Black students. Other universities across the South already had desegregated — but often amid a backdrop of violence.

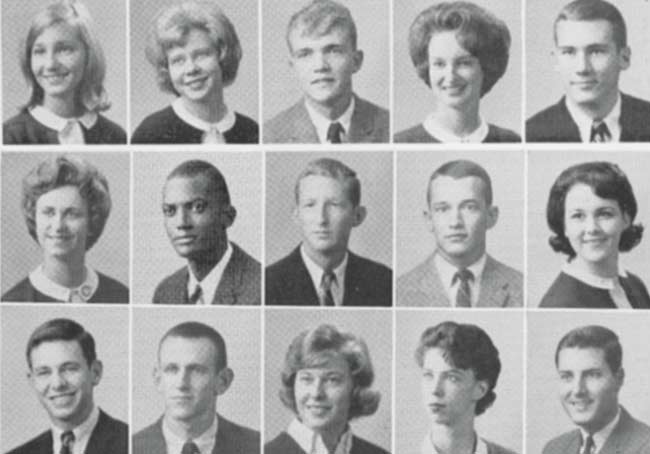

At USC, Henrie Monteith, Robert Anderson and James Solomon were the first allowed to enroll, and the university’s initial step toward desegregation happened peacefully on Sept. 11, 1963. A statue depicting those first three students the day they registered for classes is planned for installation near McKissick Museum in 2024, and a groundbreaking for that monument will be held on Monday, Sept. 11.

As important as that day in 1963 was, the university’s desegregation was a process, not a once-and-done event. In the years that followed, more Black students would enroll — a trickle that would eventually become a steady stream. Today, nearly one-fourth of the university’s freshman enrollment is composed of underrepresented minority students.

That’s a far cry, of course, from the university’s enrollment six decades ago. One wonders what it was like for Black students who enrolled at USC immediately after 1963. What were their experiences at what had been an all-white university?

“I wasn't quite sure what I was going to face,” says Jim Bowers, who transferred to Carolina from Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville, after his freshman year. “I was no stranger to hostile, unwelcome attitudes and treatment by whites. But I was a believer in Dr. Martin Luther King's non-violent passive resistance strategy.”

Bowers lived in Maxcy College, one of four Black men in that dormitory. “We didn't experience any violence on campus, which was very key,” he explains, though he also says he was careful when and where he went off campus to avoid racial confrontations.

“During my three years of matriculation there, USC was not an oppressive environment. It just wasn't inclusive,” Bowers says. “The 15 or more Black students studying at USC while I was here were not integrated into campus life. We were not invited to belong to fraternities and sororities. No Blacks played any varsity sports.

“We didn't even go to football and basketball games for fear that we might encounter some some violence.”

Bowers graduated from Carolina in 1967, attended law school at Harvard University and returned to USC as the School of Law’s first Black professor in the early 1970s. He went on to a long career in corporate law.

"These young men and women were trying to navigate in a world that was overwhelmingly foreign to them with very little guidance and support."

A.P. “Archie” Williams III had been raised in a family steeped in the civil rights movement. His father was president of the state chapter of the NAACP. Archie had just graduated in 1964 with stellar grades from Booker T. Washington, a prominent all-Black high school near the university campus. He immediately joined the USC Marching Band, becoming the band’s first-ever Black member.

He recalls instances when a random white student would direct an ugly racial slur at him in the hallways, but he says he never felt threatened when he was a student. Grades were Williams’ chief concern. Though he had been an honors student in high school, the first semester was a jolt.

“Going into the fall I got three Cs and an F, and it kind of shook me up a little bit,” Williams recalls. “I didn’t feel like the professors were being fair in grading my work.”

After more middling grades in his second semester, Williams left USC and enrolled in mortuary school in Ohio. He returned to Carolina several years later, found helpful advisers including Ada Thomas in the School of Business, and successfully completed a business degree.

“He proved to himself that he could graduate with better grades,” says his wife, Calvernetta Williams, who graduated from USC in 1973 with a master’s degree. “He refused to go to the commencement ceremony, though. He always felt like he had been cheated that first year.”

Williams went on to a long career managing his family’s funeral home and has remained a fan of Gamecock sports.

Bobby Donaldson, an associate professor of history at USC and executive director of the university’s Center for Civil Rights History and Research, says Black students who enrolled at USC in the early years of its desegregation felt the burden of family expectations and additional scrutiny from an all-white faculty, many of whom had never taught Black students.

“Those students knew that they had to work harder, they had to jump higher,” Donaldson says. “These young men and women were trying to navigate in a world that was overwhelmingly foreign to them with very little guidance and support.”

The law required previously segregated universities like USC to admit students without regard to race. “It did not say you had to provide a support system. It did not say you had to integrate the faculty or integrate the staff,” Donaldson says. “And guess what? For almost a decade, you had students of color on campus studying and learning in a space where they had no one else in the administration or on the faculty who looked like themselves.”

That many of those students succeeded in the early years of the university’s desegregation is a testament to their perseverance and resilience — and a reminder of how much has changed in the decades since.