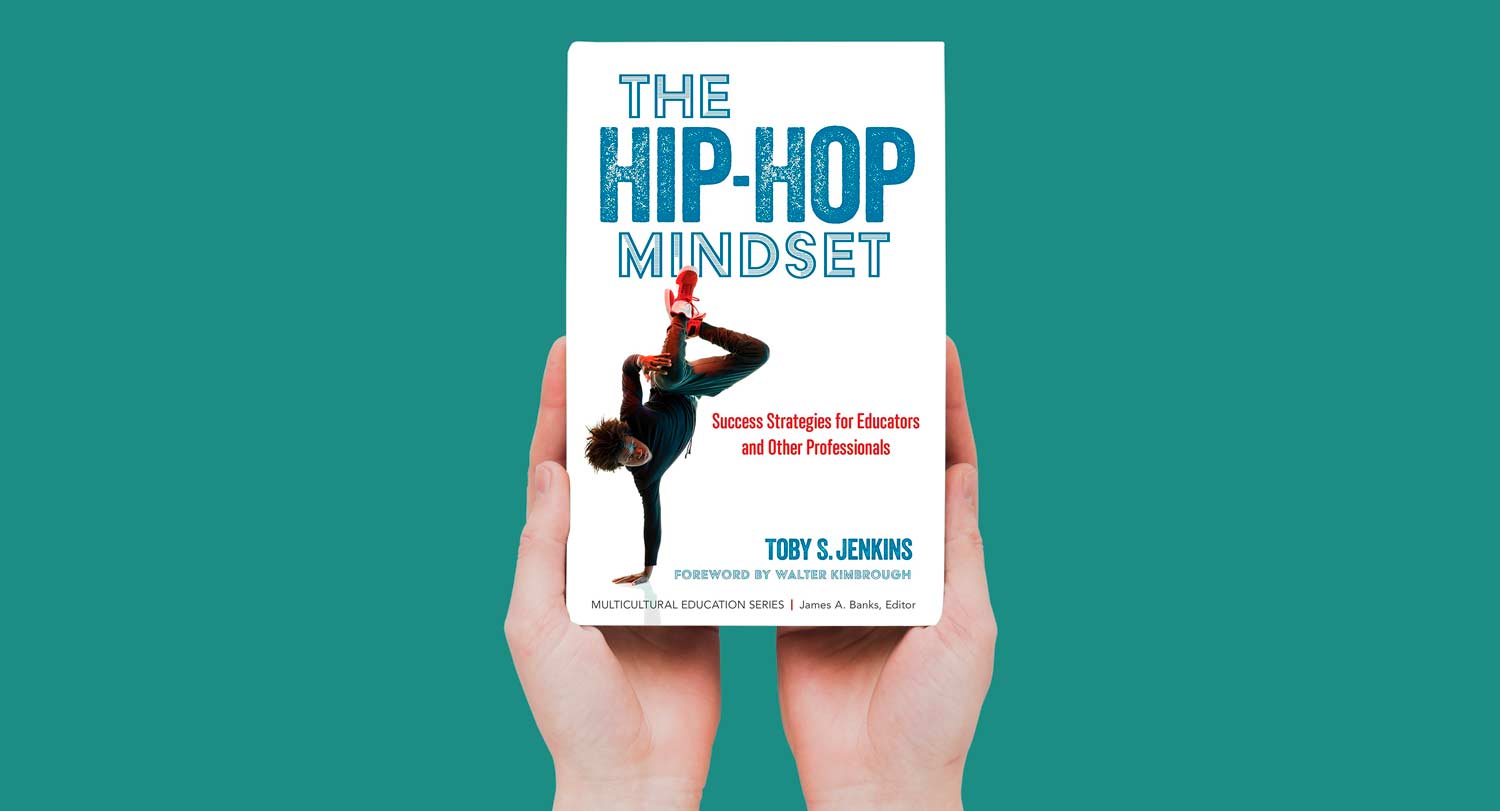

Toby Jenkins is a professor in USC’s Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the College of Education and associate provost for faculty development. Jenkins’ latest book, The Hip-Hop Mindset: Success Strategies for Educators and Other Professionals (Teachers College Press), combines her scholarly expertise with her lifelong appreciation for hip-hop music and culture.

Before we dive into what the book is, let’s talk about what it isn’t. Some people might assume The Hip-Hop Mindset is about lesson plans or how to use hip-hop to get cred with students. But you’re very clear that this is not a book about using hip-hop as a classroom tool.

Right. The book really focuses more on professional development and leadership than instructional practice and pedagogy. I’m talking about how people embrace hip-hop values or ethics — ways of thinking, being and doing that have been embraced by hip-hop culture for many years. It’s a type of leadership scholarship motivated by my mining of hip-hop culture, but looking beyond the traditional spaces of business and leadership education as the only places where we can learn practices or habits of mind associated with professional success.

A lot of the book is about empowerment through hip-hop, and one metaphor you focus on is the microphone. Holding the mic, owning the mic, passing the mic. When you have the mic, you control the message.

There are so many great metaphors within hip-hop culture — there are objects that you can reinterpret and reimagine in different ways — but the microphone in particular can literally change the course of an emcee’s life. It can change their bank account. It can change how many people are listening to them, even if they’re in some isolated, marginalized community. No one is listening to you, and then all of a sudden you’re given a microphone.

The book really focuses more on professional development and leadership than instructional practice and pedagogy. I’m talking about how people embrace hip-hop values or ethics — ways of thinking, being and doing that have been embraced by hip-hop culture for many years.

It can be the same in education. Getting a position as a teacher or a principal, a professor or a director, in some ways that becomes your microphone. That becomes your opportunity to speak, to control what’s being said, to control the message, to broaden the message. The critical question is once you are given that power, how will you use it?

One idea that you explore is the cypher, where people take turns rapping, trying to top each other but also encouraging each other. You describe one you encountered where a group of young boys were rapping and cheering each other on in a parking lot. It clearly resonated. What can an educator learn from that practice?

There are several things that educators can learn from cyphers if all they were doing before was just using hip-hop music and rhymes to teach content. First, there’s the act of listening deeply to the person in the center. It decentralizes the idea of “sage on the stage” or who is the expert in an educational setting. For the two or three minutes that a young person is in the middle, everyone surrounding them is deeply listening to their words, and that makes them feel incredible.

The other thing is the immediate reward. Education is mired in delayed gratification. You’re always waiting for someone to give you praise. You’re waiting for test scores. You’re waiting for degrees. You’re waiting for diplomas. You’re waiting, waiting, waiting. With the cypher, people are clapping you up immediately and understanding how much you need that to keep going. So, we can ask ourselves how are we encouraging not only our students as instructors but, if you are a supervisor, how are you clapping up your staff or your team members?

It’s also a competition, right? You see that as a positive component of the hip-hop mindset, something to be celebrated.

The field of education sometimes runs away from being competitive, and I think they’ve often gotten it wrong. That’s why educators today don’t want to focus so much on competition, because competition that pits students against each other or labels them as smart and not smart, that kind of competition is not healthy.

But look at an environment that promotes healthy competition like a hip-hop cypher, where everyone is clapping for the person in the middle, but then as soon as that person gives up the spot and passes the mic, the next person is determined to take his spot. We see that in sports, where there’s this healthy sense of confidence that comes from healthy competitive environments. I think we need more of that in education.

You outline three main values of the hip-hop mindset: drive, approach, posture. You break down each in the context of hip-hop culture, using examples of different artists. Help us understand how the larger values are applicable in education.

Drive is about seeking opportunity. It is about being competitive, ambitious and hungry for a chance to show the world what you’ve got. Approach is how you approach your work once you get that opportunity. It is about being creative and innovative in the work that you produce. Hip-hop culture isn’t about sustaining the status quo. Posture is how you show up professionally. But posture can be intimidating for people who don’t feel like they’re dynamic public speakers or who feel like they can’t manage a stage like a performer does. Not a lot of jobs require you to perform on a daily basis, but teaching is one of them. You’re on a stage, whether you’re teaching at an elementary level or college, and that requires practice.

You know, my editors gave me some pushback because I used Beyoncé as an example of a performer who really shows up and shows out — because Beyoncé is on a different level, and that can seem intimidating to expect a teacher or professor to try to command their metaphorical stage on a Beyoncé type of level. But the point is that Beyoncé works hard and practices. And it’s the same with educators. The thought that you could get up every day and be a public speaker and not practice? That’s crazy. Yeah, maybe the thought of that seems exhausting, but you know what? That might be what it requires. Being an educator might require us to take that time to honor and recognize that keeping people’s attention is important.