From creating social mobility by supporting first-generation students to providing resources for community members who need them most, the University of South Carolina is dedicated to strengthening our state and improving the lives of its residents.

It’s work that goes beyond the college campus and extends into every corner of South Carolina.

Read on to find out how USC and its alumni are serving the most vulnerable populations and building a brighter future for South Carolinians.

For someone who is still in training to become a K-12 mental health counselor, Ansley Rabon already has seen up close the dire need for more such staff in South Carolina schools. While she was volunteering as an intern in an Upstate middle school, Rabon experienced the aftermath of a shooting.

“I was there the following day working with the counseling teams,” she says, “and it really highlighted the critical need for accessible mental health services and culturally sensitive counselors.”

Rabon, who is in the counselor education program in USC's College of Education, is now part of the first cohort of graduate students in Project PRISMS (Providing Resources to Increase School Mental Health Support), a U.S. Department of Education-funded program that aims to help fill the pipeline of counselors and therapists for high-needs schools in South Carolina.

The project intends to recruit and train 72 students in five years. As part the fellowship program, students receive funding and clinical placements in high-needs school districts, such as Richland 2, Lexington 1 and Aiken school districts. Graduates commit to work in those and other high-needs districts in the state for at least two years after graduation.

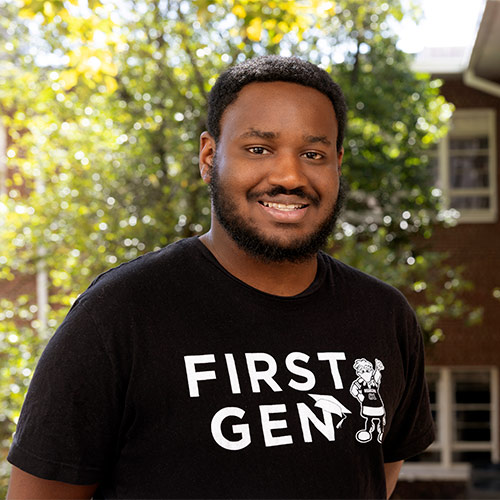

At USC, one in five students identifies as first-generation: someone whose parents have not completed a four-year college degree. For decades, TRIO programs have paved the way for first-generation students to flourish before, during and after college with life-changing resources and support. And the university is doing more than ever to help this important and growing population.

Curtis Pernell, a first-generation student from Dillon, South Carolina, chose USC for both undergraduate and graduate school. While USC was always his dream school, he didn’t know if college would be financially attainable. The TRIO Gamecock Guarantee program helped him cover tuition, and Pernell also found a home away from home at USC thanks to the mentorship of TRIO staff.

“My first semester, I was contemplating dropping out, but getting involved with TRIO programs showed me that college was for me. Director (Althea) Counts was the first person to instill in me the confidence to do what I’m doing now,” he says.

Now, Pernell is giving back as a graduate assistant in TRIO’s Opportunity Scholars program at USC. After he completes his doctorate in higher education, he aims to direct a program that helps low-income students.

USC’s CarolinaLIFE is a nondegree, residential, inclusive program for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. LIFE stands for Learning is For Everyone. The program empowers students to explore their career interests and hone their employment skills through individualized coaching and access to University of South Carolina courses.

A key tenet of the program is social engagement. CarolinaLIFE encourages students to join campus organizations. For Ruth Bollinger, ’20, this was a major draw to choose USC.

“I asked at each program: ‘Have you ever had a student go through the Greek system?’” she says. “Some said yes, some said no. One said, ‘Oh, we have honorary.’ And I’m like, ‘No, that’s not the same. I want to be fully initiated.’”

With support from staff, Bollinger became the first CarolinaLIFE student to join a sorority. She also became the first to serve on a student body president’s cabinet. After graduating, she joined CarolinaLIFE staff to work as a lead coach.

One of her proudest contributions has been coordinating with the USC Alumni Association to start an official CarolinaLIFE chapter. While the experience is different for everyone, Bollinger can attest that the program helps participants build not only life and employment skills, but confidence, too.

Monique Garvin (’19 dual master’s, social work and public administration) knows how critically important her work is in combating abuse in South Carolina’s communities.

As deputy director of the Violence Against Women Act Program and South Carolina Human Trafficking Task Force at the South Carolina Attorney General’s Office, her goal is to prevent abuse and to minimize its consequences. Her efforts focus on domestic violence, human trafficking, sexual assault, stalking and harassment.

Garvin came to her current position with nearly a decade of professional experience, including serving with Teach for America in the state. She credits experiences while at USC for changing her career trajectory.

“The emphasis on policy and community work as well as the clinical skills helped me find my niche in social work and as a public administrator,” she says.

Garvin calls domestic violence a public health crisis, but adds that the number of incidents can be difficult to capture.

“While we do have some data around what's happening in South Carolina, we know that the numbers are greater than we probably anticipate,” she says. “My aspiration for our state is that we can create communities that are free from violence where everyone can thrive.”

Sarah Hall says she’s always been service oriented with a desire to contribute to her community. It’s something the fourth-year medical student at the University of South Carolina has understood most of her life. Hall served as a leader in USC School of Medicine Columbia’s chapter of Future Leaders in Medicine, an organization that raises awareness and funds to fight childhood cancer.

"Being able to connect with patients and families from a clinician standpoint, and then from a philanthropic and research standpoint — it's been a really unique experience," Hall says. "To be able to feel the depth of that has been pretty profound."

In 2024, Hall directed an event to raise money for the local Curing Kids Cancer mission in Columbia, South Carolina. The foundation has raised more than $30 million over the past 20 years, and it has USC roots, too. Alumnus Clay Owen and his wife, Grainne Owen, started the organization in honor of their son Killian, who died of leukemia in 2003.

The organization supports pediatric cancer research and care at some of the top children’s hospitals in the country. Recently, the Owens fulfilled the organization’s $1.2 million endowment to PRISMA Health, where the outpatient hematology and oncology clinic was renamed the Gamecocks Curing Kids Cancer Clinic.

According to Marion Boyce, West Columbia’s police chief, nearly half of the calls for help its department receives are related to mental health or substance use – people who may just need resources or support.

“When I took an oath 18 years ago at West Columbia, it was to serve people; it wasn't to lock people up… I'm more interested in how we positively impact community,” Boyce says.

He’s found a way to do just that with the help of two recent alumni of USC’s College of Social Work. Erin Flaxman and Sophie Sumpter were hired by the West Columbia Police Department and the S.C. Department of Mental Health to develop and staff “WeCo LEAD.”

A national initiative, LEAD (Law Enforcement Assisted Deflection) is a community-based alternative to prosecution for people accused of nonviolent, low-level offenses whose behavior stems from substance use, mental health challenges or poverty.

“LEAD offers other options to address the root causes of behavior, as opposed to putting someone in jail and encouraging the cycle to go on,” Flaxman says. “If we can address some of those issues and provide resources, we can improve the community and create a more inclusive and safe space.”