Reducing crime through reading

Education students go 'behind the fence' to help incarcerated youth improve reading skills

Posted on: May 22, 2017; Updated on: May 22, 2017

By Kathryn McPhail, mcphailk@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-8841

The convoy of cars carrying 15 eager University of South Carolina English education students is stopped by an armed guard and a drug-sniffing dog before entering through the towering barbwire fence surrounding the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ). For three weeks each May, the master’s students go behind the fence into the DJJ’s Birchwood High School to help the incarcerated youth improve their reading strategies .

“Our job here at the College of Education is to prepare our students to teach all types of learners. To do that, sometimes you have to leap outside of your comfort zone,” says English and literacy education professor, Mary Styslinger.

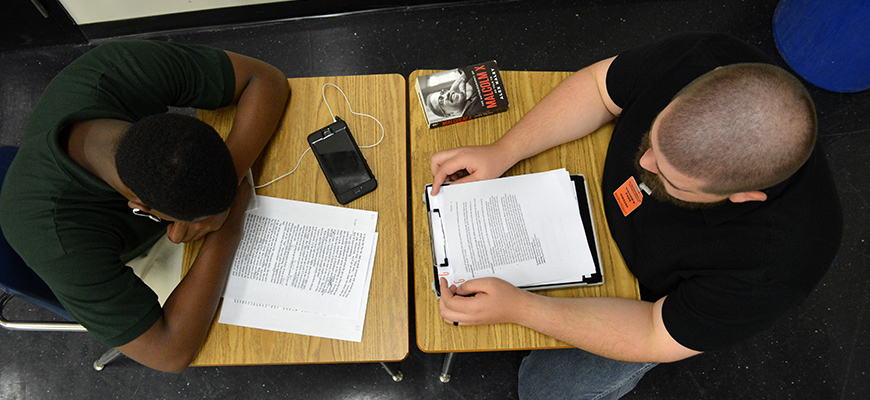

Styslinger has been bringing her secondary English education students to Birchwood for eight years. They work one-on-one with the teens, most of whom are struggling readers, to increase their reading comprehension while hopefully, fostering a love of reading.

Each Carolina student is challenged first to select a book that they think their DJJ student will enjoy. They base their decision on information gathered from an extensive literacy interview with DJJ students which takes place at their first meeting. At the second meeting, the education students provide DJJ students with three choices of young adult literature from an approved list. Some popular choices include anything written by James Patterson, Walter Dean Myers, Sister Souljah, Ellen Hopkins, Tracy Brown and Coe Booth.

“Most of these students would say they are bad readers because to them, a good reader is a fast reader. But, reading is not a foot race,” stresses Styslinger. “We want them to understand that a good reader comprehends what they are reading and makes sense of it, which can require rereading a passage, predicting, connecting, visualizing, questioning, inferring or even reading out loud.”

Reading out loud is something 16-year-old Yavaundre R. isn’t very comfortable doing.

“I read to myself mostly,” says the soft spoken teen. “I thought I could better understand the information if I read silently, but they bring in these books and we read out loud. It really is helping me enjoy reading more.”

Yavaundre is working with grad student Kaila Morris, who says she’s learning right alongside her student.

“It just makes me reflective of my process of teaching, especially when it comes to teaching reading and it just gives me a different perspective and experience. Yavaundre was missing words in his reading. These miscues can sometimes change the meaning. I encouraged him to pay closer attention as he reads,” says Morris.

Yavaundre hopes that his improved reading skills will help him pass his GED, which might in turn, decrease his likelihood of committing another crime once released.

“We know there is a correlation between increased literacy and decreased recidivism. If we can help students improve their reading comprehension and pass the GED, they may be more likely to continue their education when they are released," says Styslinger.

Styslinger stresses that by encouraging often impulsive youth to stop and think deeply about what, why and how they are reading might help them be more reflective on other decisions they make in life.

"If these students can learn to reflect as they are reading, then perhaps they can transfer this art of reflection to other aspects in life and make healthier decisions in the future," says Styslinger.