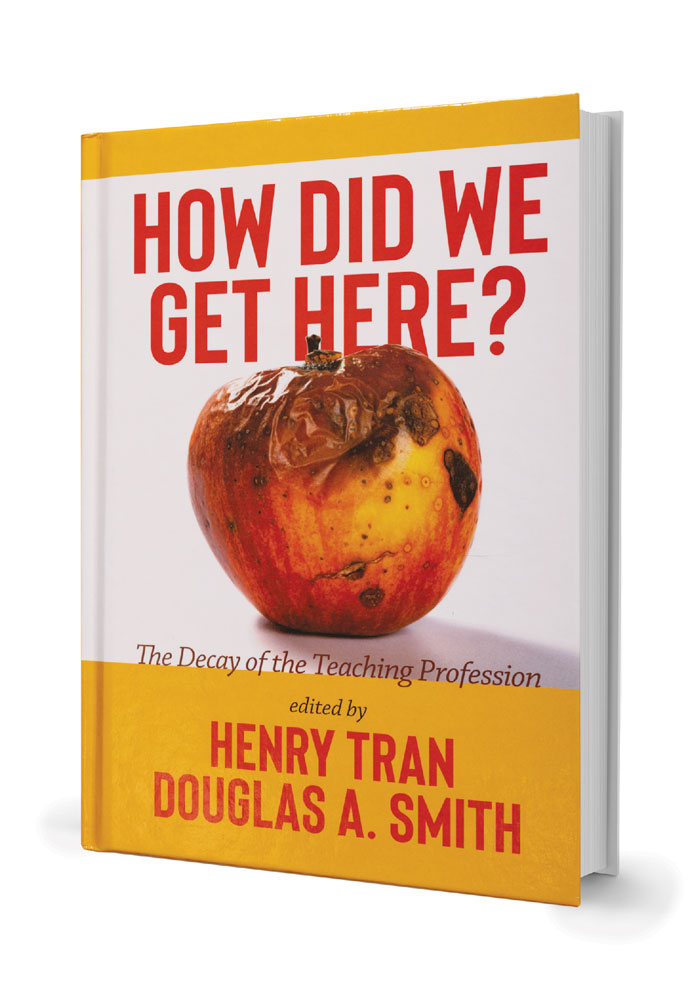

It’s no secret: public school teachers are leaving the profession at an alarming rate. How Did We Get Here? The Decay of the Teaching Profession (Information Age Publishing, 2022), edited by University of South Carolina associate professor of education Henry Tran and Iowa State University associate professor Douglas A. Smith, explores the causes and consequences of teacher attrition in South Carolina as a way to shed light on the larger crisis affecting America’s schools. We talked with Tran about the issue.

The book is about the teacher exodus in general, but you focus on South Carolina. What’s so instructive about the Palmetto State?

South Carolina is interesting for numerous reasons. In recent years, local media has been reporting about the teacher shortage crisis on an annual basis. Per data from the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention and Advancement, each year the state sees fewer individuals completing an initial education preparation program in South Carolina when compared to people leaving public school districts, which is reflective of broader trends across the nation. Moreover, South Carolina shares characteristics with most of the initial handful of states that saw teacher strikes in 2018 and 2019, such as being a conservative “red” state that prohibits collective bargaining for school districts, having a large concentration of citizens in poverty and having a history of underfunding education.

We hear a lot about low teacher pay and teacher burnout. Relative to the rest of the nation, how does South Carolina stack up in these areas?

I’m not aware of any comparative data on teacher burnout across states, but that information does exist for salaries. According to the most recent data (2019) from the annual teacher salary benchmark report by the National Education Association, South Carolina teachers averaged a starting salary of $37,550 when compared to the national average of $41,163. That puts South Carolina at 41 among the 50 states. However, after adjusting for cost-of-living differences across states, South Carolina’s average beginning teacher salary is adjusted to $40,994, as compared to the national average of $41,163, putting the Palmetto state at the rank of 33 in the nation.

What other big factors are leading teachers to leave — or not to pursue the career in the first place?

We chronicled decades of research on the status of the teaching profession and teacher working conditions to understand how the profession devolved to the point of nationwide shortages and teacher strikes. Our conclusion, based on feedback and input from teachers, potential teachers, principals and superintendents across several decades, is that it ultimately boils down to a lack of respect — a lack of respect on a macro societal level, as demonstrated by the lower relative pay of teachers when compared to other similar working-class professionals, despite the escalating workload, and lack of respect at the micro school level, as demonstrated by poor working conditions, dwindling teacher autonomy over curricular decisions, parent respect, student respect and lack of administrative support. This lack of respect not only serves as a driver of turnover but a barrier that prevents candidates from considering the occupation in the first place.

Your introduction begins with the 2019 teacher walkout, which drew an estimated 10,000 people to the State House for a “day of reflection.” Was that an inflection point heralding imminent change? Or just a symptom of dissatisfaction?

The 2019 teacher walkout in South Carolina was part of a larger movement that spread like wildfire across the nation. These strikes and walkouts were made possible due to an early victory for teacher activists in West Virginia in late 2018 and the advent of social media activism that powered and inspired the #redfored movement, similar to what we saw with the #metoo and #timesup movements. Many of the early teacher strikes in the movement took place in conservative right-to-work states like South Carolina, where collective bargaining is weak or non-existent and systematic underfunding of schools is the norm.

The first section of your book explores the legacy of segregation. How has that history continued to affect the profession?

One of the lasting legacies of segregation on the teaching profession is the scarcity of teachers of color in the field, especially relative to the demographic makeup of their students. Scholars have noted that when desegregation became the law of the land, many school districts pushed out their Black educators, given that both Black and white students could now be taught by white educators. The fact that the numbers never recovered from this, coupled with negative school experiences many Black students face, including a disproportionate share of the discipline, results in barriers against diversifying the teaching corpus.

Dating back to the 19th century, teaching was seen as “women’s work” and the poor pay reflected that. How has that gender bias changed or not changed in the 21st century?

Teaching is a largely female-dominated profession, and it is no coincidence that, at the same time, it is a profession that has long struggled with attaining and maintaining respect. This is seen reflected on numerous fronts, such as teachers’ lower relative pay as compared to professionals with other comparable education and training requirements, their lack of professional autonomy, being under-resourced, receiving violence from students and parents and facing constant public scrutiny. In my research, I have heard about the perception of the lack of respect for the profession from both present teachers and college students who intentionally chose not to become teachers. Much of this disrespect comes from the belief, held by many, that teachers are primarily babysitters employed to provide day care services.

The debate about the funding of education has always been politically charged. What’s your response to critics who might complain of a political bias in the book?

Many of the core factors at the heart of the teacher strikes, such as ensuring there are adequate education resources and funding flowing into the classrooms, improving the working conditions in schools and offering more competitive pay to teachers, should not be partisan issues or controversial for anyone who claims to support public education. The situation is divisive because students are involved. Consequently, they are often weaponized against educators who speak out or take action to instigate change, based on the assumption that student needs and educator needs are mutually exclusive and that teachers should sacrifice their own well-being for the benefit of students. This couldn’t be further from the truth. We know from a large body of research that teacher working conditions are directly related to teacher retention, and both are linked to student outcomes. Putting it succinctly, as former Gov. Easley of North Carolina has noted, “teacher working conditions are student learning conditions.”