At least 777 incarcerated people died in South Carolina from 2015 to 2021 — some by suicide, some at the hands of others; some due to medical issues, some from drug overdoses. Some died years after being placed in custody, and some died before a judge had even heard their case.

None of these people had been sentenced to death row.

In a first-ever analysis of deaths in South Carolina prisons, jails and youth detention centers, USC School of Law assistant professor Madalyn Wasilczuk and her students have compiled a report that aims to increase transparency in corrections facilities across the Palmetto State.

“Just knowing these numbers gives us the opportunity to think about whether some of these deaths can be prevented,” says Wasilczuk, who directs the law school’s Juvenile Justice Clinic and teaches courses about the death penalty, sentencing practices and youth justice.

Law schools tend to focus most criminal law-related instruction on the process that puts people in prison, Wasilczuk says, but focus much less on what happens to individuals when they are in jail awaiting trial or in prison after trial.

“Students who will become lawyers involved in any part of the criminal process should understand what life in jails and prisons looks like, its effects and the ways it can become invisible to the outside world,” Wasilczuk says. “As a public university, we have a responsibility to make sure we produce lawyers who are capable of taking on the legal needs of all of the people of our state, and that includes the approximately 38,000 people in South Carolina who are behind bars on any given day.”

Facilities are required by law to report deaths of incarcerated people to the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance and the South Carolina Department of Corrections, but the forms to report their death data are inconsistent and, in some cases, outdated. As a result, some details, such as the specific location of death within a facility, may not be provided.

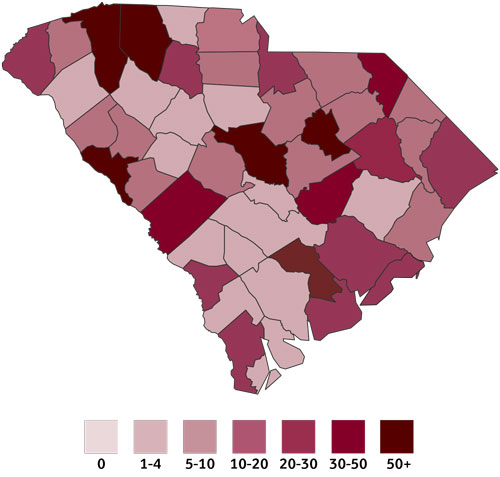

For their report, students in Wasilczuk’s spring 2022 course on Eighth Amendment law and litigation filed Freedom of Information Act requests with 196 facilities and agencies in South Carolina for data on inmate deaths, which generated 161 responses. Thirty-four facilities, including 13 county jails, either didn’t respond or refused to provide information.

That data-gathering process was pioneered by Andrea Armstrong, a professor at Loyola University New Orleans College of Law who has compiled a database of prison deaths in Louisiana. Armstrong’s research is supported by Arnold Ventures, a philanthropic foundation that supports public policy research in criminal justice and other areas and has provided seed funding to Wasilczuk’s data-gathering project. Data gathered in South Carolina shares a website with the Louisiana project.

“The data we’ve collected should be considered in conjunction with allegations of poor conditions in facilities to determine how resources should be better deployed and to recognize where incarceration may be leading to excess deaths,” Wasilczuk says.

According to the data collected by the class, in-custody deaths during the study period

were equally distributed among Black and white prisoners — 381 from each group. Of

the remaining 15 deaths, race was listed as unknown. Black prisoners were somewhat

more likely to die of medical causes, while white prisoners were much more likely

to die by suicide, drug overdoses and accidents. Black prisoners,

in turn, were much more likely to die from violence.

The study also found that men accounted for 94 percent of deaths during the 2015-21 period, which is consistent with males’ 93 percent share of the incarcerated population in South Carolina. Medical deaths were the leading cause of death for men and women, though men were more likely to die by suicide. Deaths attributed to violence and accidents belonged exclusively to men.

More than two-thirds of deaths in custody were caused by medical illness, which points to the state’s aging prison population. And while South Carolina’s prisons had the highest homicide rate of any prison system in the country from 2001 to 2019, the 42 violent deaths from 2016 to 2021 comprised only 5.41 percent of all deaths behind bars in the state during that period.

“I think there’s this perception that prisons are violent because the people inside them are violent,” Wasilczuk says. “But we have lots of prisons outside of South Carolina where there aren’t any violent deaths or very, very few. And so we have to ask ourselves ‘Why do those places have so much less violent death with similar populations?’ and then question whether prisoners become violent, in part, because of facility conditions.”

Wasilczuk has continued requesting and compiling more deaths-behind-bars data with students in the spring 2023 section of the Eighth Amendment law and litigation course. She says making their findings more widely available could lead to reforms that may reduce future deaths in the incarcerated population.

“For people who lose family members and friends behind bars, it’s important for them to be able to get answers and have some measure of confidence that what they’re being told by authorities is accurate,” Wasilczuk says. “As a state, we can do better, and I hope we’ll do better.”