There’s no mystery about the disappearance of Ace Harlem. Born in 1947, his story ended just as quickly as it began.

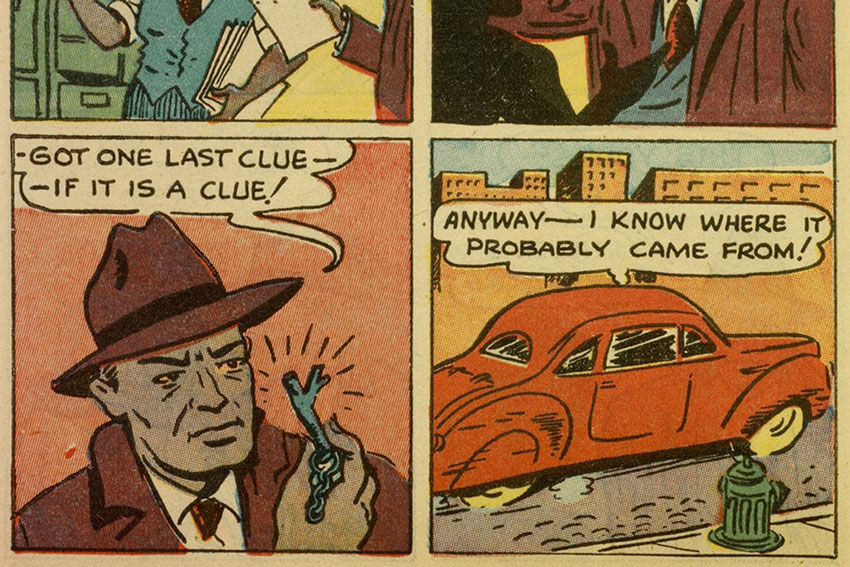

Picture this: a Black police detective comes upon the scene of a crime and traces the evidence to robbers holed up in a downtown apartment. A struggle ensues. Only one survives.

Ace Harlem lives to pursue his next adventure.

Only, his next adventure never happens, because the comic book’s publisher, Orrin C. Evans, couldn’t get anyone to sell him more newsprint for his next edition of All-Negro Comics.

It’s the kind of roadblock he and other Black creators encountered in trying to tell Black stories in comics during the “golden age.” Harlem’s story, along with so many others, is lost to time.

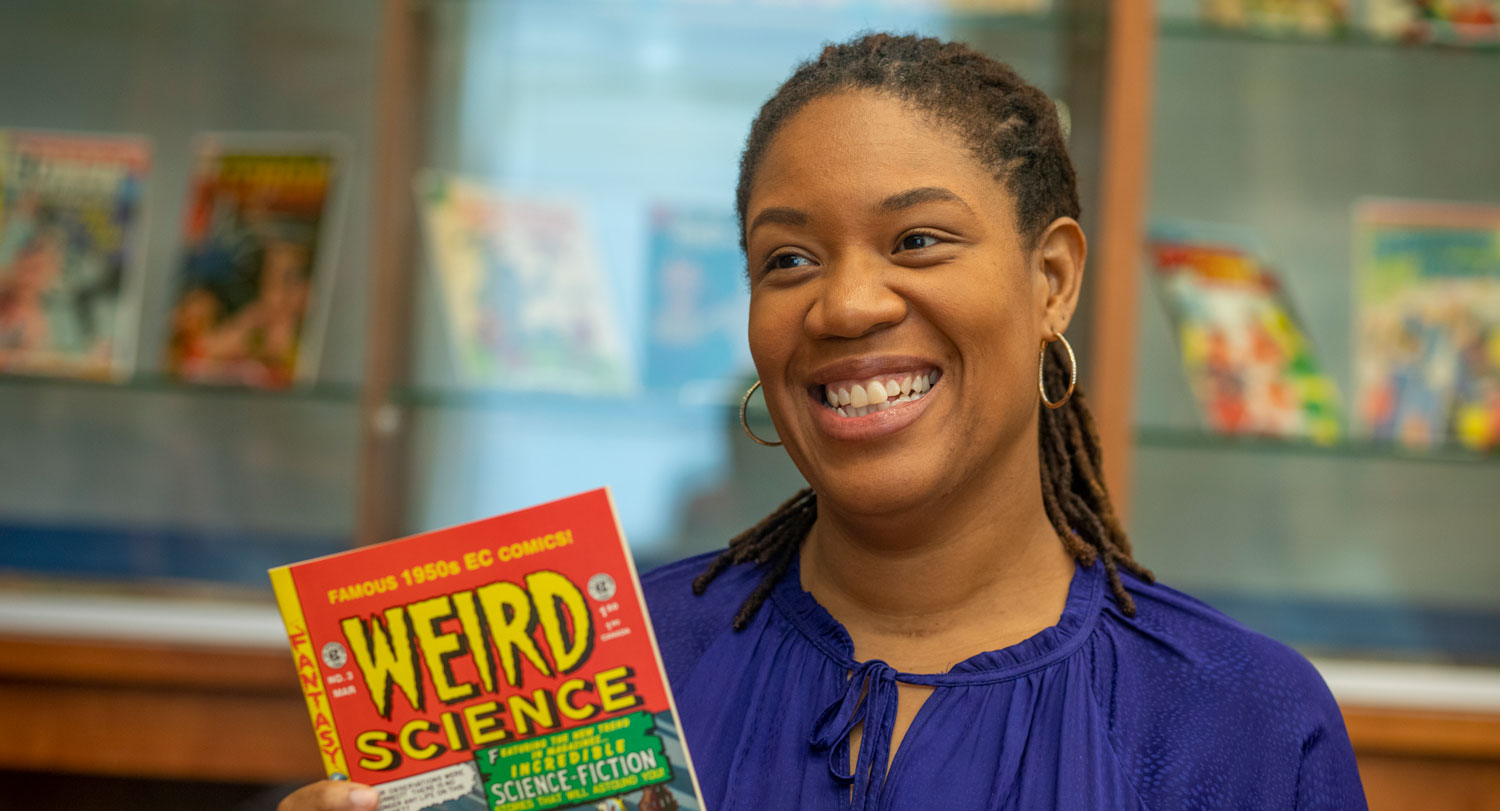

Qiana Whitted, English and African American studies professor at USC, writes of Evans’ ill-fated publication in her new book, Desegregating Comics: Debating Blackness in the Golden Age of American Comics.

Published this spring and edited by Whitted, the book brings together 15 experts on Black representation and contributions in comics of the era. Whitted’s essay focuses on the first comic book created expressly by Black artists about Black characters, for Black audiences.

“The first issue of All-Negro Comics is an incredible milestone,” Whitted says. “But it’s also a tragedy.”

“There were always Black readers and others who said, ‘This is not right, these kinds of caricatures don’t represent us, and comics can be better without them.’”

Black art in the Golden Age

The golden age of comics, from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s, was a time of great creativity and popularity in the comics industry. Superheroes like Batman, Captain America and Wonder Woman started on adventures that captivate imaginations to this day, while detective serials, like Will Eisner’s “The Spirit,” set the bar for artistic quality and storytelling.

Whitted has studied the golden age of comics for more than a decade and is part of a comics studies working group made up of faculty from different departments throughout the USC system.

Whitted’s previous book, EC Comics: Race, Shock, and Social Protest, took an in-depth look at social justice comics from the publisher known sensational titles such as “Tales from the Crypt.” This book won the most prestigious award in the comics industry: the 2020 Eisner Award for Best Academic/Scholarly Work.

Her new book takes a broader look at the golden age, with chapters addressing different issues, artists and publications. One essay, by USC Sumter’s Andrew Kunka, reckons with problematic characters in legacy series, including Will Eisner’s “The Spirit.”

While this series made Eisner synonymous with the best, his famous detective had an African American sidekick named Ebony White. As the name suggests, the character embodied Black stereotypes, which Eisner would later acknowledge as racist. He eventually revised the character and at times phased him out.

Whitted says Black readers were one of the main drivers of changing comics, even from the earliest years when stereotypes were rampant.

“There were always Black readers and others who said, ‘This is not right, these kinds of caricatures don’t represent us, and comics can be better without them,’” Whitted says. “They loved comics and continued to do so even when the stories disappointed them.”

Black publishers and artists also sought to change the industry from within. Black-owned newspapers created their own serials, and in spaces thought of as “white,” many uncredited Black artists worked the production line.

E. Simms Campbell was an African American artist whose publisher kept his identity under wraps so that his work could be distributed widely. A few Black artists, like Matt Baker and Alvin Hollingsworth, rose to fame in the predominantly white comics industry because of their distinctive styles.

“One of the goal of the work I’m doing is to demonstrate that African Americans and people of other races have always been a part of the industry,” Whitted says.

The past and the future of comics at USC

Whitted hopes to see USC become a hub for the growing field of comics studies. The comics working group, sponsored by the Humanities Collaborative in the College of Arts and Sciences, gathers regularly to discuss their research and teaching approaches.

“All of us come at comics from a different angle,” Whitted says.

“Our goal is to try to think about ways that we can relay to students and to the public about the importance of comics studies and what it means to study popular culture here at USC.”

In 2020, University Libraries Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, received a donation of 180,000 rare comics books. Members of the working group and their students have helped to process the collection, which offers a valuable resource for the many classes on comics at USC and for further research in the field.

In addition to scholarship on the history of comics, USC’s faculty offer insight into the future of the industry, as creators struggle with a changing publishing landscape and continue to work toward more diverse and equitable representation in the comics and adaptations.

“It’s a testament to one of the cool things about comics, which is that they can pass through many hands and their stories can evolve in exciting ways,” Whitted says.