They call themselves the Math Scholars — a group of eight sixth-grade students at Currey Ingram Academy near Nashville, Tennessee.

It’s a name that neither the students nor their parents could have imagined a couple of years ago. These 11- and 12-year-olds with learning differences had long struggled with mathematics, having trouble staying on task and performing basic math skills.

That changed in Dawn Pilotti’s classroom. Pilotti, a long-time mathematics teacher and an online doctoral student in USC’s College of Education, uses tools to make mathematics “more real” to the students. And with an assist from her doctoral advisor, USC associate professor Kristin Harbour, the students now count mathematics among their favorite subjects.

Pilotti has been teaching mathematics and special education for 26 years — the past 10 at Currey Ingram Academy, a research-based, model school for students with learning differences. This is her second year teaching the group of students now known as the Math Scholars.

“This group of students was really struggling in math when they came into fifth grade,” Pilotti says. “We were working on some kindergarten-level skills last year in fifth grade. They were years behind in where they needed to be.”

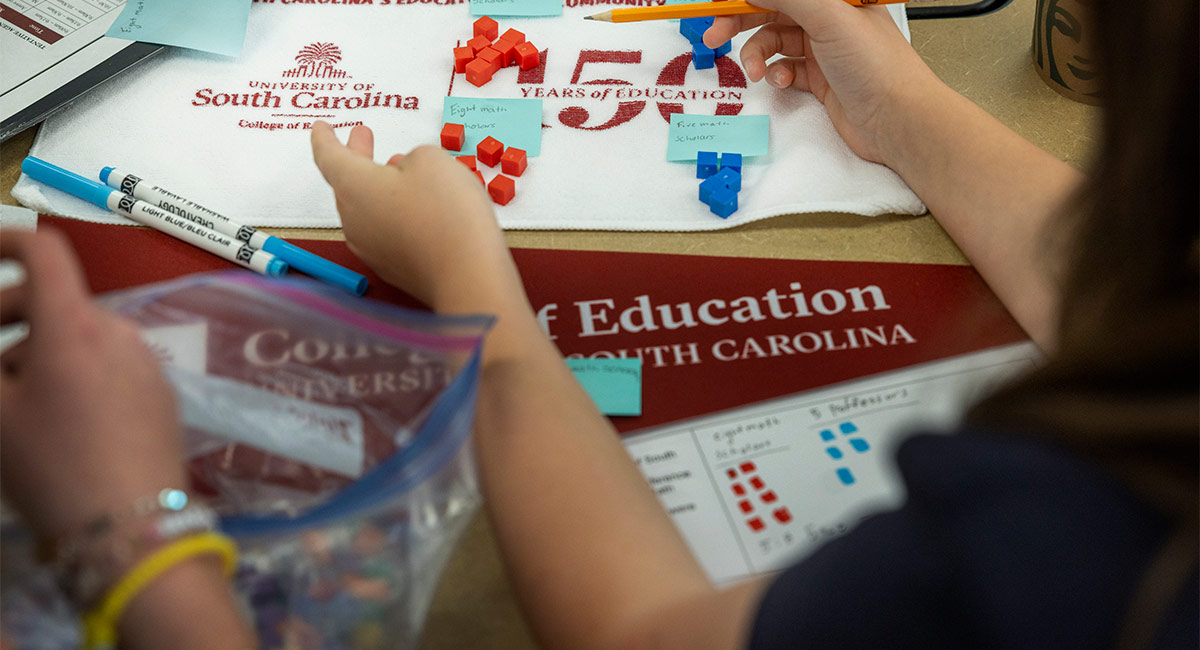

Pilotti teaches mathematics by focusing on real world problems and using a lot of manipulatives to help students understand concepts. It makes mathematics a visual subject for the students at the school, 70 percent of whom have language-based learning disabilities. The Math Scholars now are performing nearly on grade level in mathematics.

And in April, they brought their stories — and their math skills — to a USC classroom.

The seeds for the trip started with a story on the College of Education’s website about Pilotti’s experience in USC’s online doctoral program concentrated in the STEM field. The story mentioned she was drawn to the program partly because of the chance to work with Harbour, whose expertise is in the intersection of mathematics education, special education and professional development. The story, which included pictures of Pilotti’s students in her Tennessee classroom, intrigued the students, who were thrilled to see themselves on a university’s website. And they had a lot of questions about Harbour.

Harbour and Pilotti talked frequently about her mathematics students, discussing how Pilotti could take what she was learning in her USC doctoral program and apply it in a practical way with students and teachers at Currey Ingram. Soon, Harbour was meeting the Math Scholars on their computer screen and learning more about what they were doing in class.

“Dawn is an exceptional teacher for them, and she wanted them to know that other people were in their corner and that I was one of them,” Harbour says. “I think that gave them the idea that this person in South Carolina cared about their math understanding and was working with their teacher to help make them confident mathematicians. And they really felt empowered by that. They were reaching beyond just their classroom.”

Soon, Harbour was learning more about their stories.

“For me, it's been this magnificent experience to see how I can still build relationships with kids at a distance,” Harbour says. “And seeing how that can influence them has been a really eye-opening experience.”

But another surprise came for the students. Their parents, teachers and the College of Education arranged for some in-person face time with Harbour. In April, they made the nearly seven-hour road trip from Nashville to Columbia, where they were welcomed to the USC campus and spent the day solving mathematics problems, collecting data on a scavenger hunt, showing their work to their parents and sharing their story with the USC community.

“I love that we got to do the same kinds of math that we do at school in Nashville in South Carolina, and our amazing math teacher Ms. Pilotti and Dr. Harbour were both there together doing it with us,” says Math Scholar Elle Steele.

For the parents, it was a chance to celebrate their children’s accomplishments. After researching 25 schools for children with learning differences, Kenda and Bob Lovecchio moved from Austin, Texas, to Nashville last year so their son Kai could attend Currey Ingram Academy. Pilotti was his first teacher.

“Math was his worst subject,” Bob Lovecchio says. “ELA (English Language Arts) was his favorite. It has switched to math being his favorite. He’s the most confident in math. He does his homework independently.”

It’s a similar story for Kimberly and David Silvus, whose 12-year-old son Grant is a student in Pilotti’s class.

“Math is the only subject he comes home and talks to me about,” says Kimberly Silvus. “He uses math homework as an excuse to not go to bed on time.”

Her husband, David, says, “He’s doing math we were not sure he’d be capable of — multiplication, fractions, division. All of it.”

Pilotti gives plenty of credit to her students, who she says are supportive of each other and work really well together. And Harbour has enjoyed the front-row seat to see the remarkable strides the students have made.

“When Dawn first started working with them, they were so petrified of math because they felt beaten down, they had just not had successes in math at that point,” Harbour says. “And just the miraculous turnaround in their learning and their confidence is truly the essence of this beautiful story.”

Ryan O’Grady said his son Elliott has thrived at the Nashville school and especially in Pilotti’s math class, a subject that was difficult for him in the past. The day at USC helped reinforce the idea that college is attainable for his son.

“To come here (to USC) and see that there are people who care, that there are professors here who are interested in the next generation,” O’Grady says. “It makes it possible to dream about what’s possible.”