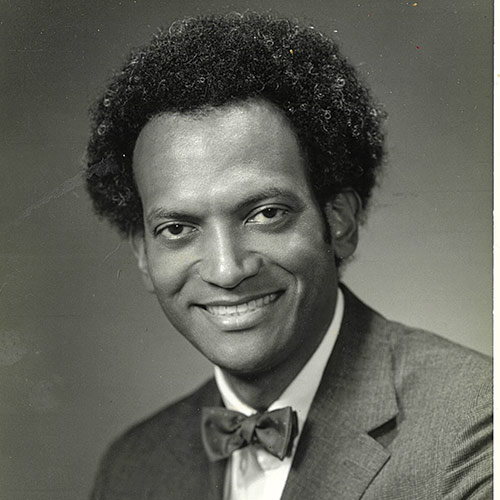

James E. Bowers made his mark breaking barriers at the University of South Carolina. He was an undergraduate student in the early days of desegregation and the first full-time African American law school professor.

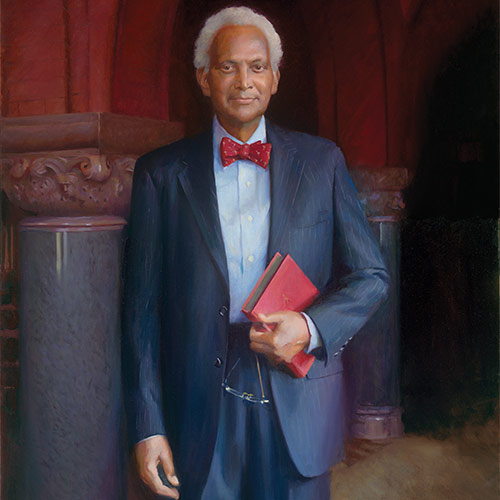

Bowers will cement his legacy with an endowed professorship in his name at the Joseph F. Rice School of Law, the first named for a Black law school professor, and an endowed lectureship series that will share knowledge about democracy and the rule of law. His portrait will hang in the reading room of the law library.

“I'm hopeful that, after I'm gone, people — Black and white — will look back to 1973 and say, ‘You know, there was a voice back then for greater inclusiveness,’” says Bowers. “That's the legacy that I've decided to fulfill.”

It’s a legacy that took him from Orangeburg, South Carolina, to USC to Harvard Law School and to a career practicing at the top levels of corporate law. It’s also a legacy that includes a deep commitment to education.

An early commitment

Growing up in Orangeburg, South Carolina in the 1950s and ’60s, Bowers and his family were active in the civil rights movement. He attended the 1963 March on Washington, hearing the words of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. ring out from the Lincoln Memorial across the National Mall.

As a teenager in the Jim Crow South, he participated in protests against segregation and sit-ins at businesses that refused to serve Black customers. He saw first-hand the work of lawyers such as Matthew Perry, who represented Henrie Monteith in her legal case to become one of the first Black students to attend USC, and Earl Coblyn, one of the principal lawyers responsible for the suit to desegregate the Orangeburg public school system. It was a vision that stayed with Bowers, allowing him to imagine a life as a civil rights attorney fighting against racial injustice.

In 1963, the year the University of South Carolina admitted its first three Black students since Reconstruction, Bowers entered Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee. Bowers was happy at Fisk, where civil rights icon John Lewis was a classmate and where student activism was front and center, but he also kept up with the news coming out of his home state.

“During my year at Fisk, I said, ‘I've got to get back home. I need to be a part of the change that is happening.’ I was going to be a part of what I call the second wave of Black students to enroll in the student body,” he says. “It was the feeling where I had to be part of something historic that was going on.”

In the fall of 1964, Bowers was one of 16 Black students who were a part of that second wave at USC, a tiny fraction of the student population of about 7,000.

Enrolling at Carolina meant giving up on what he calls a “normal” college experience. “From the very outset, my single focus at USC was my academic studies because I wanted to demonstrate to the university administration that Blacks belonged at USC and could successfully handle the work.”

What he found on campus was a social environment that wasn’t hostile to Black students, but also wasn’t inclusive. So, Bowers dedicated himself to his studies and getting to know faculty members, especially those in the political science department. Two of them, Glenn Abernathy and Don Fowler, became lifelong supporters and promoters, playing key roles in Bowers’ academic studies and career.

The call of Harvard Law

By his third year on campus, he knew he wanted to study law. As a senior, he was notified of his early acceptance to Harvard Law School by a Western Union telegram, and he began his journey to Cambridge.

“That was a tough transition. I had always felt that I had been prepared for higher academic studies. But when I got to Harvard, it was a different world. It was the cream of the crop from all 50 states and a lot of students who graduated from Ivy League schools,” he says. “I had to really buckle down and study almost around the clock. It wasn't just me; that was a part of the culture at Harvard Law School. And everybody was vying to get good grades because that opened doors afterward. We literally studied night and day. That was back when we had Saturday classes, so the only time off that we had was Saturday night. But when Sunday came around you hit the books again.”

Bowers says his first year at Harvard was challenging but invigorating. “I found it very exciting because I had a huge thirst for learning back then. And I was drinking from a fire hose.”

During his time at Harvard, he realized the broad range of opportunity for lawyers. He started rethinking his plans to become a civil rights lawyer and looked toward corporate law.

“Not only do you need good Black civil rights lawyers to represent Blacks who experience struggles of discrimination in life, but I realized that you also need Black lawyers trained on the corporate side,” he says.

He wanted to be able to advise Black lawyers going into the corporate world, along with African Americans graduating from business schools who were starting to integrate and advance in large corporations. He also wanted to be in a position where he could demonstrate to white clients that a Black lawyer was capable of managing and advising them on corporate affairs.

But the path to being corporate counsel to some of the country’s largest and best-known companies was interrupted for a few years, when his alma mater reached out to him about coming home to teach at the law school.

“I'm hopeful that, after I'm gone, people — Black and white — will look back to 1973 and say, ‘You know, there was a voice back then for greater inclusiveness.' That's the legacy that I've decided to fulfill.”

Back to USC

When Bowers was first accepted at Harvard, his undergrad professor Abernathy told him he’d like to see him return to USC as a faculty member. At the time, Bowers just shrugged it off.

But in the summer of 1972, when Bowers was working in Washington, D.C. a USC law professor called and asked if he would teach a summer program for Black college students in South Carolina who aspired to go to law school.

Bowers says he never envisioned teaching law; he was planning to practice law. But he had been a counselor in USC’s Upward Bound program when he was an undergrad and worked in a similar program at Harvard focusing on underrepresented students who wanted to attend law school. He accepted the summer job at USC.

He enjoyed it, and faculty members had the chance to observe him. Soon after he returned to Washington, he got a call from USC offering him a full-time teaching job. It would require a shift in his career, but he was intrigued. And when he told his parents in Orangeburg about the offer, “I could see the glow in their eyes.”

He was 26, and while he didn’t think it would be a lifelong career, he saw the need. There were just a few Black law students at USC, and the law school had never had a full-time African American professor. Richard T. Greener, the first African American appointed to the faculty at USC during Reconstruction in 1873, taught part-time at the law school.

“I said, ‘I'm going to go down and I'm going to try to do a couple things. No. 1, I'm going to learn how to teach, because I have to be effective first and foremost. But No. 2, I'm going to try to increase the African American student population there, which I was able to do.”

When he decided to leave the job four years later, the university provost did not want to accept his resignation. Along with allowing Black students to see a successful role model, the provost believed it was important for all students to experience teaching interactions with a nonwhite professor to enhance their ability to function in a multicultural society.

“I went to South Carolina under one set of assumptions, but now I had an equally important task, and that was relating to white students because I had a platform to change attitudes and perceptions.”

An anecdote: After his first year, one of his contract law students, who was white, approached him. “He said, ‘Professor Bowers, I just want to thank you. In my many years of education, you’re the first Black person to teach me. And I've been enriched by the experience.’”

Bowers says he didn’t want to leave USC, but knew he wanted to get more experience practicing law. He tried to find a suitable law position in Columbia, but couldn’t make that work. Bowers says he always figured he’d return to the USC law school, but his career as a corporate lawyer in the Northeast took off. He still enjoyed teaching and had adjunct teaching positions at the University of Connecticut and Yale law schools.

That commitment to education, he says, is part of his DNA. In the years following the Civil War, his paternal great-grandfather amassed a large amount of real estate, owning 270 acres of farmland near Bennettsville, South Carolina — a size unheard of during a time when Blacks who owned land had just 5-10 acres. On that land, his great-grandfather established a school for the children of formerly enslaved people, and his daughter taught there.

“It was very important to him to pass along education opportunities to ex-slaves,” Bowers says. “He had 18 children and encouraged all of them to pursue higher education. Most did and became successful educators, ministers, and one was a doctor.”

Bowers’ mother was a teacher all her life, and her father taught mathematics, astronomy and masonry construction at two historically black colleges in North and South Carolina in the early 1900s, before he died at age 42 in the Spanish flu pandemic.

“When I started reflecting on my teaching and my commitment to teaching I pretty much said, ‘I need to honor the legacy of my ancestors and family members who had a strong commitment to the education of Black people.’ I started thinking, during what I call my twilight years, that I’ve got to reconnect with the University of South Carolina because it was such a meaningful place to me.”

He hopes the lecture series he is sponsoring will help people, particularly students, understand the U.S. government structure and constitutional protections of checks and balances, along with highlighting the importance of voting. Bowers is also working with USC Press on publication of his memoir.

“I guess, when you put it all together — the professorship, the lectureship and ultimately the memoir — the whole package will paint a picture of what it was like for one Black person growing up in South Carolina during the ’50s and ’60s, what that person experienced and what led that person to the University of South Carolina, Harvard Law School and a return home.”