Millions of times smaller than a grain of salt, nanocrystals have become extraordinarily useful in electronics, drug delivery, biological imaging and beyond.

In electronics, their unique electrical properties enable the development of smaller, faster components. In medicine, they can be engineered to target specific cells or tissues.

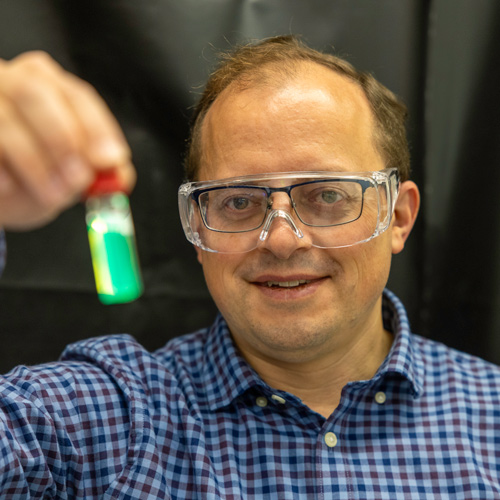

As powerful as they already are, Andrew Greytak wants to perfect them. The University of South Carolina chemistry professor has been studying nanocrystals for a long time, and the quest for a perfectly homogeneous nanocrystal is supported by his latest NSF grant.

“The real focus we’ve been developing in the last couple of years is on nanocrystal surface chemistry, which we call structurally indexed surface chemistry,” Greytak says. “When people make these solutions of nanoparticles, they’re not making a single structure — they’re not all identical. You can say 90 percent of the particles are within this size range, or most of the particles look spherical or cubical — but they’re not all identical. We want something that’s more homogeneous.”

That goal has led Greytak’s team to making what are called magic-size nanocrystals, so named because they have a specific or “magic” number of atoms and are even smaller than normal nanocrystals.

“They are nearly homogeneous, but we’d like them to be atomically, precisely homogeneous. We see it as sort of a fundamental challenge,” Greytak says, noting that the challenge is worth pursuing because a more precisely homogeneous batch of nanocrystals is more stable and more predictable in its reactivity.

And when it’s being used for bioimaging applications such as cancer detection, that extra level of reliability is key. In addition, because magic-size nanocrystals are so small — one to three nanometers in size — they could be used in contrasting dyes for biomedical imaging to access spaces between human cells that are too tight for larger nanocrystals, Greytak says.

More precise homogeneity also improves the stability of nanocrystals, which increases their shelf life and would allow execution of more complex tasks, particularly in drug delivery and other biomedical applications, he says.

Nanocrystals may be small, but their impact is big — and Greytak hopes to increase that impact through his research.

In addition to his work on magic-size nanocrystals, Greytak is studying a new class of matter called metal-halide perovskite materials, which can make highly fluorescent quantum dots, a type of nanocrystal made from semiconductor material. He says there is keen interest in using quantum dots made from metal-halide perovskite in lighting and solar cell applications.

“But they have some issues with stability, so there are questions on how to modify their surfaces to increase their stability and enable practical applications,” he says. “That really helps to motivate us. If you’re looking for basic research problems, there are lots of things you can look at, but you want to do something that’s going to be beautiful or useful — or both."