Uniquely Ours

USC's new law school highlights history and progress at every turn.

By Craig Brandhorst

Walk through the University of South Carolina's new law school and two things are apparent in the design — a sense of history and an eye toward the future.

The classrooms convey the formality of the legal profession but are equipped with state-of-the art media capabilities, including ceiling microphones. An old-school reading room designed for quiet study complements a bustling, 24-hour student commons area named for South Carolina’s largest law firm, Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough.

And then, of course, there are the two courtrooms, named for two towering figures from South Carolina’s rich legal history.

“I tell people all the time, ‘We don’t want this to be a building that could just as easily be at the University of Iowa or someplace else,'” says Robert Wilcox, ’81 law, dean of the School of Law. “This is the University of South Carolina. We’re proud of the historical ties to the profession in the state, and I’ve noticed a lot of people walking through the building are very taken by that — this is a place that is uniquely ours.”

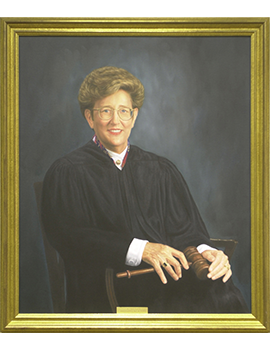

Karen J. Williams Courtroom

One of the more dramatic features of the new law school building, the Karen J. Williams Courtroom seats 300 and is suitable for jury trials and appellate arguments, moot court and mock trial competitions. The space, which features an 1870s heart pine judge’s bench originally used in a State House courtroom alongside modern media technology, will also be used as a classroom and auditorium.

“In the old law school, we could bring a court in for certain purposes, but they were on a stage in an auditorium. It felt like a makeshift court, like pretend. This is going to be the real thing,” says Wilcox, adding that the courtroom also helps establish expectations for students hoping to pursue a career in law. “This room conveys an important message to students, which is, ‘You’re entering a different kind of profession. All the dignity represented by this room — that’s what you need to have as you enter this profession.’”

And the fact that the courtroom is named after Karen J. Williams, the first woman chief judge of the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, only reaffirms that message.

“In addition to being smart and a trailblazer, when I think of Karen, and when I think of the courtroom that’s now named in her honor, I think of dignity,” says Wilcox. “You would never meet a more dignified person. She just represented what a lawyer ought to be.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by many in the S.C. legal community, among them former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of South Carolina Jean Toal, ’68 law, who mentored Williams during and after law school.

“She certainly had people who wondered if she was up to the challenge,” says Toal. “These were people who didn’t know her very well. She was more than up to the challenge.”

Ultimately, Williams was appointed to the Fourth Circuit in 1992 and served as chief judge from 2007 until her retirement in 2009. Williams’ name was also floated as a potential nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court during the administration of George W. Bush.

“Karen was just such a beacon of encouragement to so many women. At the same time, her legacy is so much broader than that,” says Toal. “She was a brilliant jurist who went to the very top of the legal profession in this country, but her head was not turned by her great success.”

Williams died from early-onset Alzheimer’s in 2013. Her portrait now hangs on the wall to the right of the bench in the courtroom that bears her name.

The bench in the Karen J. Williams courtroom was originally the bench of the Supreme Court of South Carolina and dates from the 1870s. It was formerly in the S.C. State House.

State-of the-art video screens complement the more traditional aesthetic of the vintage 1870s bench and enable multimedia presentations.

Floor-to-ceiling windows on the north, east and south sides of the courtroom provide plenty of natural light, which can be blocked with electronically operated drop screens.

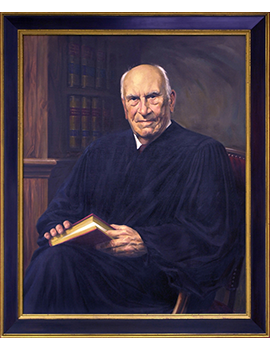

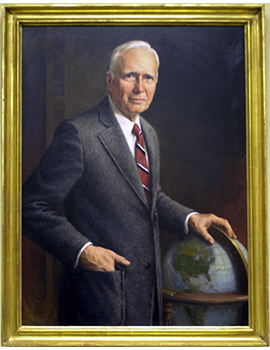

A portrait of Karen J. Williams hangs to the right of the bench. Williams, ’80 law, was appointed to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1992 and became the first female chief judge of that court in 2007. She retired in 2009, after being diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease, and died in 2013.

Law Library

The new law library is actually slightly smaller than its predecessor in the former law school building on South Main St., but you’d never know it walking through — because two-thirds of the print collection is now stored on compact shelving in the basement.

“The space is used much more efficiently,” says Duncan Alford, associate dean and director of the law library. “With the compact shelving, users can retrieve items themselves — they just press a button and the shelves move. And freeing up all that space allowed us to create attractive study spaces like the reading room, like the group study spaces.”

In fact, there are more than two dozen such spaces around the building, ranging from the soaring, cathedral-like reading room to smaller group tables and study rooms.

“We had all of four group study rooms in the old building; we have five on each floor in this building,” says Alford. “Students like to be in open areas. And they like to see each other.”

Students also like amenities and comfort, particularly if they’re going to spend three or four hours hunkered down in the library, going over case law. To that end, the library has been furnished with comfortable chairs and sofas, as well as tables with power outlets. And, of course, wi-fi is strong throughout.

“It’s just attractive space, and it’s quiet,” says Alford. “Libraries are that third space — where people want to be together but they want it to be quiet. I think the open tables along the windows on the Bull Street side will be very popular with students, where you’re up in the trees. It’s open-feeling and very calming.”

But the law library is not just a comfy, quiet study zone. It also serves as a public archive for printed legal materials.

“We are the only research law library in the state, so we have an archival responsibility for South Carolina law and South Carolina legal history,” says Alford. “We get a direct appropriation from the General Assembly to collect, preserve and make those materials accessible, so we are open to the public.”

The net result is a library that’s tech-ready, user-friendly and thoroughly modern in its functionality but still feels like a library.

Coleman Karesh Reading Room

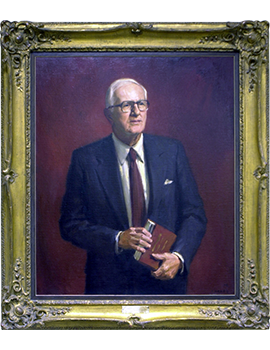

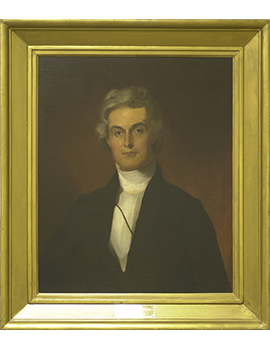

The new law library may not have a namesake yet, but the adjoining reading room certainly does. The Coleman Karesh Reading Room honors one of the most esteemed professors in the law school’s 150-year history.

Karesh, ’23, ’25 law, practiced law in Columbia for 12 years before joining the law faculty in 1937. Over the next 35 years he established himself as a nationally regarded expert on wills, trusts and estates. Upon his retirement in 1972, the library in the then-new School of Law building on South Main St. was named for him. In 2017, the reading room in the new law school was similarly named in his honor.

“If you talk to lawyers who went to law school here in the ’50s and ’60s, and they say, ‘I went to school in Petigru (the law school’s home before South Main),’ what they really mean is, ‘I studied under people like Coleman Karesh,’” says Wilcox. “He was one of several faculty at the time who were so well respected in their fields that the courts would cite to them for authority.”

Wilcox isn’t exaggerating.

“Even when I got to law school, after he retired, law students made sure they had a copy of his ‘skinny’ because there was nothing more valuable,” he says. “I still have them on the shelf in my office, ‘The Karesh Notes.’”

Indeed, just mentioning “The Karesh Notes” gets an enthusiastic response from many School of Law alumni, including former chief justice Toal.

“Oh yes, that was the Bible — still is!” says Toal, who studied under Karesh. “I can tell you, in the 27 years I was on the S.C. Supreme Court I had many matters come before the court that involved his area of specialty. Coleman Karesh’s notes were the first stop I made in research, always.”

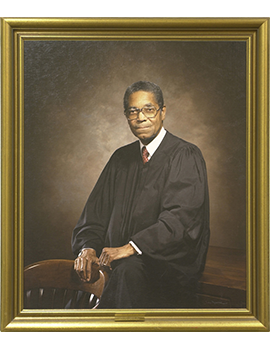

G. Ross Anderson Historic Courtroom

Compared to the spacious grandeur of the Karen J. Williams Courtroom, the G. Ross Anderson Jr. Historic Courtroom feels intimate. Constructed from the original woodwork and marble from a former Richland County courthouse built in 1935, but with modern technology incorporated, it is designed to introduce law students to the physical atmosphere of law.

“When you walk in, you feel like you have been transported into a courthouse. It does not feel like a classroom. You can forget that you are in a law school,” says Wilcox.

The space is also a nod to South Carolina’s rich legal history, though incorporating a reconstructed South Carolina courthouse into a state-of-the-art building was more than an exercise in nostalgia.

“When you’re doing a moot court argument, or a mock trial argument, it works best when you fully get into the role as if it were a real case,” says Wilcox. “You want to argue it just as if your client were sitting in the row behind you. It will be almost impossible to miss that experience in this courtroom.”

Of course, the biggest presence in the room may not be the imaginary client but the courtroom’s namesake — Anderson, S.C., native George Ross Anderson Jr., ’54 law.

Anderson, who worked for U.S. Senator Olin D. Johnston while in college and then served in the S.C. House of Representatives from 1955 to 1956, achieved prominence in the legal community, first as a plaintiff’s attorney in Anderson County. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed him to the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina, where he presided over federal cases until his retirement in 2016.

Greenville attorney Reid Sherard, ’00, ’04 law, clerked for Anderson after law school and later conducted an in-depth oral history interview with him for the S.C. Bar Foundation. He describes Anderson as a man of strong political opinions who nonetheless inspired respect among adversaries.

“He is unabashedly a Democrat, but even his critics would say he's smart as hell. You can always respect the ability of the person you’re up against, no matter what you think about their politics,” Sherard says. “He would make it fair, but he would make it very difficult for you to claim he was wrong.”

Naming the new courtroom in Anderson’s honor is a fitting tribute, according to Sherard.

“He really believes that the trial work is where justice is meted out,” Sherard says. “Judge Anderson did not decide any substantive motion without a hearing. He wanted the lawyer to have to come in and make the argument. He wanted to hear it. He didn’t want to just read it. He felt like that was necessary in terms of making a decision.”

When the former Richland County Courthouse was torn down in 1980, the original oak woodwork was saved and kept in the former law school on South Main St. “We darkened the wood slightly, and now it’s even more impressive,” says Robert Wilcox, dean of the School of Law.

Some of the marble from the original bar of the 1935 Richland Country Courthouse was repurposed for the bar in the G. Ross Anderson Jr. Historic Courtroom. “They replaced a few pieces that needed to be replaced, but you can’t tell where they did it,” says Dean Robert Wilcox.

A wooden floor was installed in the well of the court, improving acoustics for arguments.

Classrooms and Commons

The law library is the go-to destination for research, and the reading room is ideally suited for focused study, but sometimes law students need a place where they can socialize and work at the same time. Welcome to the first-floor student commons.

Accessible via the courtyard or from the outside, the Student Commons is open 24 hours to students with a valid ID and provides a casual work space with plenty of amenities, including a variety of comfortable furniture, restrooms, microwaves and plenty of power outlets.

“There’s everything you’d need to live in there 24 hours a day, if you needed to,” says Wilcox. “It can be a student union, a noisy study space, a place to eat lunch — whatever you want it to be. If you want the quiet space, you go upstairs to the reading room.”

The Stephen G. Morrison Student Services Suite

The new building’s student services suite provides a convenient one-stop shop for student support and includes the offices of student affairs, admissions, student services, career services and the law school registrar. The suite honors the late Stephen G. Morrison, ’75, a partner at Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough until his death in 2013.

As lead counsel for clients in more than 20 states, Morrison tried more than 240 cases to jury verdict and argued more than 60 appeals in the highest courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court. He mostly represented corporations, but also did pro bono work and was co-lead counsel in the famous “Abbeville et al v. State of South Carolina,” working to achieve equity in education funding for some of South Carolina’s poorest children.

Morrison also taught as an adjunct law professor at the university for more than 30 years, beginning in 1982.

“I have dealt with wonderfully talented lawyers all over this country for 47 years, but, in my opinion, Steve was by far the best lawyer I ever met,” says Carl Epps, ’66, ’70 law, an attorney at Nelson Mullins who invited Morrison to join him on the Abbeville case. “He had remarkable rhetorical skills and wonderful people skills. He had extremely high intellectual skills. He was just a uniquely talented advocate.”

But it was another set of qualities that drove Morrison to get involved in the Abbeville case, according to Epps. “Steve had a tremendous heart. He had a great sense of the lawyer’s duty to represent people from all walks of life, and most particularly, people who by themselves have no voice,” he says. “He was devoted to trying to represent the poor and the downtrodden.”

According to Wilcox, Morrison’s ability to balance the business end of law and public service is also something for law students to emulate. “Steve showed that these were not exclusive,” he says. “That’s an important message for the profession. Certainly, lawyers are in it to make a living, but they should also be in it to do good. If you view it as all one or the other, you’ll either go out of business or you’ll lose sight of why you went to law school in the first place.”