Big game on campus

New essay collection explores intersection of college football and higher education

Posted on: August 25, 2022; Updated on: August 25, 2022

By Craig Brandhorst, craigb1@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-3681

The History of American College Football: Institutional Policy, Culture, and Reform, edited by Christian Anderson and Amber Falluca, examines the role of the popular American sport on college campuses from its 19th century roots to its contemporary cultural dominance. Anderson is an associate professor in the College of Education’s Department of Educational Leadership and Policies. Falluca is associate director at the Center for Integrative and Experiential Learning and an instructor who teaches a course on intercollegiate athletics and higher education. The two also co-curated a companion exhibit at the university’s Museum of Education at Wardlaw College.

The book begins with your chapter, Christian, looking back at the 100th anniversary of college football — or what’s generally agreed upon as the 100th anniversary, 1969 — and most of the subsequent chapters also focus on that first 100 years. Why that inflection point?

Christian: College football made a lot out of the 100th anniversary. They had a centennial game between Rutgers and Princeton, who played what is generally considered the first college football game in 1869. They had a nationwide homecoming queen. Then they had the Game of the Century between Texas and Arkansas. ABC Sports got them to change the schedule because they anticipated that these two teams would be undefeated at the end of the season, and they were. President Nixon was in the stands and awarded Texas a plaque to name them national champions. That’s one part. It’s also just how it fell out. The chapters all happened to fall within that first 100 years, except for the chapter about the NCAA versus Board of Regents decision in 1984. But even that didn’t just pop up out of nowhere. The events of the previous 30 years shaped that decision.

You also emphasize mythmaking. You write “the mythology looms larger than life in college football” and argue that we need to “understand the function and purposes of those myths.” What is that function — on our campuses or in the larger culture?

Christian: We’re always trying to make meaning out of our lives and football just seems to fit that niche by helping us make sense of who we are and who we aren’t. We all seem to give over part of our identity to our football team in the fall. If your school is 12-0, or 10-2 or 6-6, it affects your mood and your campus mood and your community’s mood. Basketball is huge, baseball is huge, they all have their own rhythms, but there’s just something about football.

Politics and history also run throughout. And some of it is eye-opening. One chapter explores the relationship between football, masculinity and the Lost Cause in the South following the Civil War.

Amber: When I read that chapter in draft form, I kept asking myself, ‘How did I not know these facts already?’ One example is the name Ole Miss for the University of Mississippi. That’s how it’s commonly referred to. On their uniforms, on the helmets, it still says Ole Miss, and you think nothing of it. Then you learn the history, that the nickname originated with the school yearbook. Then when you unpack that, you learn that the yearbook was a reference to the slave master’s wife or mistress.

So we have this sport where the student athletes are largely African-American males. It’s no question in Division I, particularly within the Power Five conferences. They’re members of the team, representing their school, but at the end of the day they’re wearing this emblem. That’s a fascinating societal puzzle, especially today. Given all that has happened with Black Lives Matter, why has that not come to bear yet? Or will it come to bear?

We mentioned the NCAA earlier. The second-to-last chapter is about Board of Regents versus the NCAA, the 1984 Supreme Court case that opened the floodgates to the commercialization of college sports.

Amber: The 1984 case speaks to this opportunistic piece of college football, with television. Who controls the revenue? Who will not only reap the rewards from the monetization, but in essence, who will have the power and influence as a result? With the NCAA prevailing, it really set an additional course — I won’t even say new course, because there was momentum already.

There’s even an anecdote about the rule change forbidding the dangerous flying wedge formation, how the NCAA perpetuated its own mythology on the matter — as you write, Christian, “to assert their indispensability.” Their timeline was wrong, they overstated their role, but whatever. They asserted their indispensability, and they haven’t lost it.

Christian: Well, let me tie this back to the 1984 case. Byron White, the Supreme Court associate

justice, had been a football player himself. In dissenting against the majority decision,

he talks about the history of intercollegiate sports. He says, look, we’re getting

far afield from the educational value. When we talk about student athletes, we’re

really moving into something that more closely resembles professional sports. Most

likely, even if they had ruled differently in 1984, we would have ended up somewhere

close to where we are now. The forces were too big.

But that ruling really sped things up.

We started with the 100th anniversary of college football. We just passed the 150th. There’s a lot of debate about those salaries, the big budgets, and the sport continues to evolve. If there were a sequel, what are the chapters?

Amber: I think what we’ll see with some of the emerging legislation is the student athletes are the drivers. You can’t ignore it. So I think we’ll see implications of Image and Likeness (NIL), good and bad. It gives a good opening for student athletes to finally say, “You’re going to market me, I’m going to get a piece of the pie.” And I think that’s great. But one thing I’m curious about is the dynamic that creates within a team structure in a sport like football. Are there the haves and the have nots? And how does that play out on the field? Does it influence how the coach interacts with the players or how they recruit student athletes?

And how about you, Christian?

Christian: You know, the origins of college football were students playing students, setting it up and organizing it. It was very student-run, almost intramural except that it was intercollegiate. It wasn’t us playing a pickup game on the Horseshoe. It was us challenging Clemson, or, in the early days, even the YMCA and high schools. I mean, you look at some of those early schedules and it’s bonkers who they were playing.

But then faculty got involved in trying to oversee it, and some were even coaches. Then you saw the administrative take over. Faculty still had a role, but their role diminished. Now we’re almost coming full circle. We’ll never have student control like in the earliest days, but there’s more student influence, like Amber was saying. So I think that if you were to write the 50-plus years since 1969, you could devote half of the book just to the student athlete. In fact, the term “student athlete” would be chapter one.

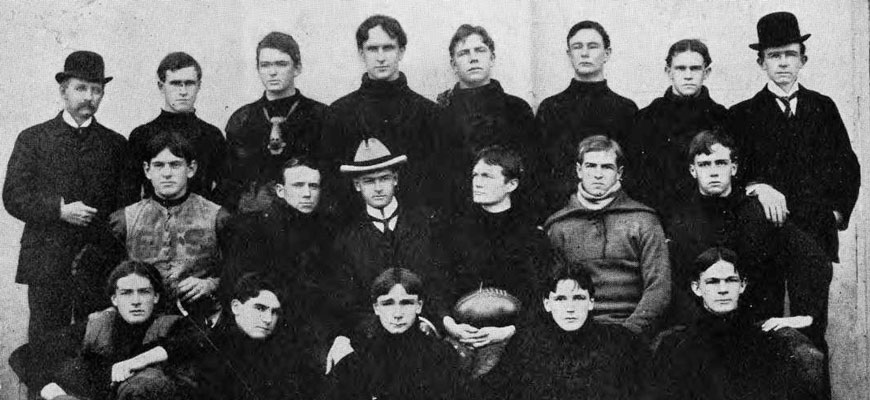

Banner image: University of South Carolina football team, 1898, Garnet & Black yearbook. Photo provided by University Libraries.