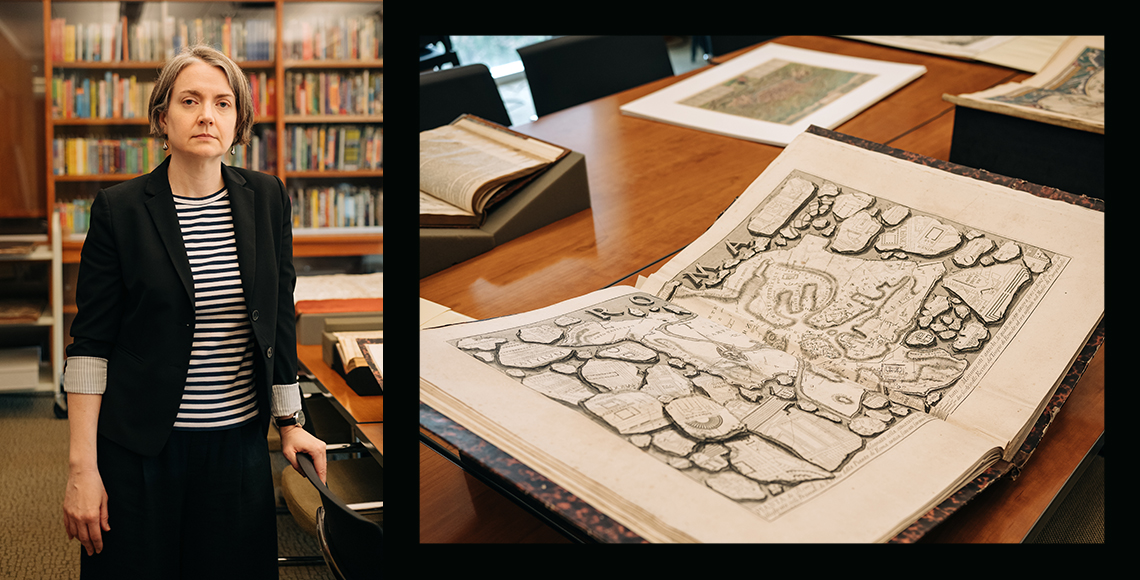

In the viewing room of the Thomas Cooper Library’s Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, rare books curator Jeanne Britton pauses beside an open atlas. Bold colors and lines depict a double-hemisphere map of the globe: Sailing ships traverse the world’s oceans and rivers slither across continents, all under the watchful eyes of Ptolemy, Copernicus and celestial beings representing constellations.

“The book that it was part of was the most expensive book at its time in the 1600s,” says Britton.

For that reason alone, Atlas Maior, by Joan Blaeu, is an impressive text. Upon closer inspection of the map, however, there’s more to discover. Antarctica, for instance, is absent from the base of the globe. California is an island. And the continents’ shapes and proportions are more suggestions than precision.

But it is these imperfections that interest Britton and her students. These imperfections are a representation of how seventeenth-century cartographers understood the world, and Atlas is a window into a centuries-old perspective.

Britton believes that a particular kind of visual — the infographic, or informational image — plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions of reality and history.

“Teaching this particular class, The Art of Information, has made me really excited about digging into materials we have (in the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections) that we don’t know we have — items we had that nobody’s really looked at,” says Britton.

Her South Carolina Honors College classes challenge students to delve into historical images and draw their own conclusions about the perspectives they convey. Students become experts on pieces that might not have been glimpsed in decades — but once they’re visible, their connections to modern society become clear.

‘A broader sense of historical time’

Take another image from the Irvin Department: The Tree of Knowledge, by Chrétien Frédéric Guillaume Roth, which is included in one of the final volumes of the French Encyclopédie produced by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, ca. 1780. The artist arranges scholarly disciplines in the style of a genealogical family tree, representing the relationships between arts and sciences. Every discipline is somehow connected, with one informing the next.

Britton believes that, in a similar way, infographics can convey the tangles of history and humanity. What beliefs shaped societal practices? Whose visions and opinions dominated decision-making? What can gazing through these windows of the past reveal about the present?

When students have the opportunity to encounter these historical images away from screens, the impact is even greater.

“I think that material encounters with objects of the past, with printed books, can be transformative, illuminating, restorative, awe-inspiring — I really do — in ways that anything on a screen just can’t compare to,” says Britton.

After she tells students to explore the collections, they’re often shocked that they’re allowed to turn the books’ pages. “I think that seeing this stuff in person and being able to handle things — as long as they’re sturdy enough — I think that it gives students a broader sense of historical time,” she says. “I think it makes them think about their own experiences with media differently.”

Britton had a similar experience as an SCHC student herself. The Carolina scholar spent a semester abroad in Leeds, England. Britton grew up in Florence, South Carolina, where she says that the oldest structures she saw were from the city’s railroad infrastructure. England, however, was a conglomeration of architectural styles dating back to the medieval era.

“That really flipped my brain inside out,” says Britton. “Did the people who grew up here just understand history in a way that I didn’t?”

‘Something new’

Encountering not just another culture, but another method of instruction, also impacted Britton. When she began teaching at the University of South Carolina in 2015, she sought to create experiential learning opportunities for her students. She appreciated the Honors College’s dedication to interdisciplinary studies and knew that an Honors class would be the perfect place to pull from the library’s special collections.

But she couldn’t just choose anything. She discovered that placing a familiar text in front of students (such as a first edition of Frankenstein) didn’t inspire the same fascination that she’d experienced abroad. To do that, she needed to recreate the act of discovery.

“For them to really get into it,” she reflects, “there has to be something new.”

To do that, she turned to fold-out images. Often unknown and uncatalogued, these images — maps, diagrams, charts — hide between the pages of larger volumes, waiting for curious students to research and share them with the class.

One such image is a route map from The Gentleman’s Magazine, published in 1775. It conveys a mapping convention that, instead of providing a bird’s-eye view of a region, provides a timeline of sights and landmarks that a traveler would encounter on a journey between cities. Printed on an accordion-pleated fold-out, this map, while not visually stunning, was the Google Maps of its day.

“I also like the whole idea that this doesn’t really fit in the book,” says Britton. “It’s too big. It exceeds the boundaries of the book.”

‘Whether an image can change your mind’

Another fold-out image that Britton teaches might be more familiar to students, but it is often included in Britton’s Art of Information class due to its societal impact. It’s an image more famous than the book that contains it: Thomas Clarkson’s The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade. The diagram of enslaved Africans packed into a ship created societal shockwaves upon its publication, and it’s still printed in many textbooks.

And the conversation about it is far from over. “There’s been a lot of good, critical academic work on whether the image is itself an oppressive image because it glorifies the suffering and dehumanizing of African people, or if it’s an effective piece of visual propaganda,” Britton explains. “It’s a meaningful image for students to engage with now, even though it’s familiar, through the lens of the class, because we’re really talking about how images work to convey information — and whether an image can change your mind.”

Britton encourages students to grapple with questions like these as they do their own research. While she provides background information and guidance for students as they orient themselves amongst these historic texts, Britton’s classes are not lectures. Students are challenged to create new knowledge as they, literally, bring historic images back to light.

There is no shortage of material in the Irvin Department, she attests. And there is always more to discover about better-known images. “No one’s ever translated it,” she says, gesturing to The Tree of Knowledge, which is written in French. She hopes that an Honors student will one day produce an English translation.

‘To last or be used and serve their purpose’

It was Britton’s own intellectual curiosity that drew her to the Honors College as a student. She recalls visiting an SCHC summer program called Adventures in Creativity that gave high school seniors a sampling of innovative, interdisciplinary courses. When she realized that she could study the history of science, blending STEM and humanities, she knew that she had found the ideal program.

“The Honors College community, and the availability and accessibility of so many Honors faculty members really made it seem like a welcoming, supportive, very smart but not stuffy place,” she reflects.

This same curiosity fuels her scholarship and teaching, inspiring new generations of Honors students to blur disciplinary lines in their own learning. The idea for her Art of Information course sparked from her fascination with one image that does just this.

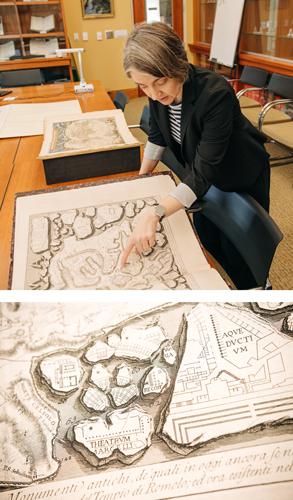

“The class really came out of and is an excuse for me to teach this guy,” she admits, gesturing to a map of Rome. “This is my guy.”

She’s speaking of Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The image in question, created in 1765, is a map of the artist’s reimaging of ancient Rome. Piranesi’s rendering of the city emerges from fragments of tablets, which the artist studied to create the map.

“He’s trying to make his reconstruction of ancient Rome look like it’s emerging from his evidence, which is the real bits of the ancient map,” says Britton. “But his version of Rome is Rome in the 1750s as if the Middle Ages and Renaissance never happened ... It’s like a picture of what primary historical, geographical classical research looks like.”

Piranesi created over 1,000 images in his lifetime. The university owns almost all of them, in his posthumous collected works, and Britton works with student research assistants to document them in a virtual catalogue called The Digital Piranesi. The images have withstood the test of time, and the project ensures that they will be more accessible to new audiences. Image by image, curious viewers from around the world can contribute to the same conversations that Britton cultivates in her classrooms about the importance of informational images.

“I think using rare books can give students a new awareness of the fleeting nature of digital media, because your Instagram account can just be deleted,” says Britton. “Piranesi wanted this stuff to last. Everyone who made all of the things in the room wanted... these things to last or be used and serve their purpose. I really do think that the hands-on experience with this material opens students’ minds, makes them curious, makes them a little bit confused, but then also engaged.”