“I saw The Exorcist at age 12,” says Julia Elliott. “It scared the crap out of me.”

While an experience like that might have frightened someone away from the horror genre, for Elliott, author and professor of women’s and gender studies, the film was an invitation. She realized, even as a pre-teen, that there was a complexity to horror that begged to be explored.

Elliott was fascinated by the power that Reagan, the film’s 12-year-old protagonist, exerted over adults. “I tapped into something that’s like: Horror is really this,” she recalls. “This film is about adolescence, and that resonated with me.”

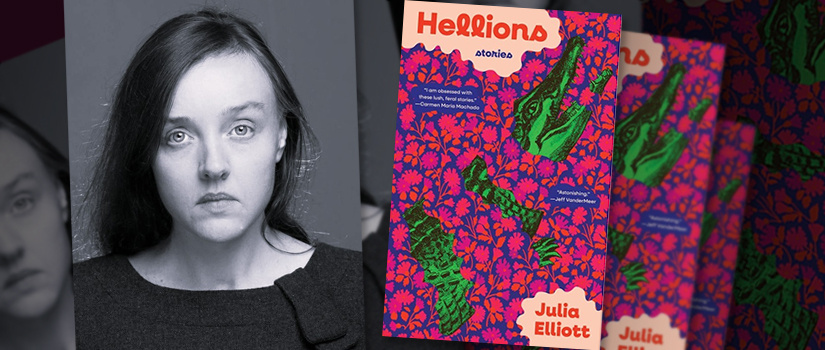

What began as an adolescent fascination now extends to Elliott’s creative and pedagogical work. In one short story of her newest collection, Hellions, a mysterious “Swamp Ape” creature (possibly escaped Clemson University) prowls the outskirts of Davis Station, South Carolina. And each fall, Elliott teaches Monstrous Mothers, Diabolical Daughters and Femme Fatales, a South Carolina Honors College course examining depictions of female monstrosity in film.

The course invites students to have experiences like Elliott’s when she first watched The Exorcist: to question the horrific, to wonder what the fears, the horrors, reveal about our society and ourselves.

“This course helped me grow in my appreciation for horror by showing how the genre reflects deeper ideas about gender and society,” says Bryce Christian, a senior Baccalaureus Artium et Scientiae (BARSC) major. “I have a better understanding of how women’s roles in horror reveal a lot about how society views them.”

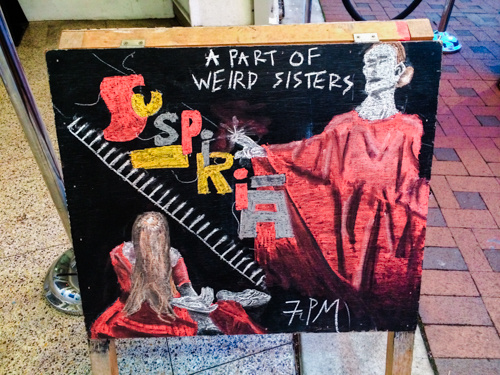

Inspired by female-directed films such as The Babadook, Raw and Jennifer's Body, Elliott decided to develop a class devoted to female monstrosity; the concept would become Monstrous Mothers...for the Honors College. Around the same time, she was working with Alison Kozberg to curate a horror film series. Kozberg was the director of The Nickelodeon Theatre in downtown Columbia, South Carolina, at the time, and she saw an opportunity to involve Honors students in the film series. When Elliott pitched the concept, a new service-learning class was born and premiered in fall 2018.

“Alison at The Nick thought of these assignments that the students could do to publicize and market and create content for The Nick, and then my students did that,” says Elliott. “They had a lot of fun.”

Over the years, the course has co-hosted horror film series at the Russell House, the Richland Library Main, The Columbia Museum of Art and even online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the location of the film series has varied, the course’s theme has remained constant: monstrous feminine, female monsters.

“You have directors of all stripes creating female monsters from different point of views, and a lot of classic horror, male-directed from the 70s, 80s and on, that is focused on female monstrosity, too, and some critics even believe that female monstrosity is kind of at the core of horror itself: the relationship with the mother,” says Elliott.

With each new series, the film selection for the course must be redesigned; Elliott aims to introduce two new films to the syllabus each year. She strives to facilitate a learner-centered classroom, encouraging discussion as the class works together to untangle different horror theories and apply them to films. Some theories focus on psychological factors, while others attest that horror depicts the anxieties of a particular era.

Many students are already fans of horror films when they register for the course, but some are new to the genre. This blend creates an environment rich in perspectives.

“I teach all these different theories and set up dialectics,” she says. “And then the students basically develop their own theory of horror... I never just stand there and talk. I always encourage the students to talk along with me about every single slide. And if they don’t, that’s kind of horrifying, because what do I do? I’m not good at lecturing.”

The students have plenty to say about the course and their involvement with The Nickelodeon Theatre’s film series. Elliott tasks the students with providing a creative introduction and program notes to their assigned film; students also decorate the theatre’s lobby to match the film’s theme.

“Promoting a film at The Nickelodeon Theatre was such a fun and meaningful experience,” Christian reflects. “I’ve always loved seeing movies there, so working with them felt really special. My team promoted Huesera: The Bone Woman. It wasn’t my first choice, but I ended up connecting with it more than I expected. It was exciting to see our work contribute to something real like helping market a local theater.”

Elliott has learned from her students, as well. They’ve shared the anxieties and concerns of their generations and how those manifest in horror films. “Also, a lot of the horror we talk about, we talk about it in terms of gender and sexuality and they have different sorts of ideological stances on that than I do,” says Elliott.

“I developed a theory about how horror can explore female rage and monstrosity in ways that feel empowering. Female rage in horror often rejects victimization and becomes a way for women to take back control of their stories and their bodies. That rage sometimes turns physical and transforms the character into a monstrous figure. I see this as the ultimate expression of the ‘monstrous feminine,’ where women break away from what is expected of them,” says Christian.

Elliott’s fiction frequently breaks from the expected and blends genres. In her latest collection, Hellions, Elliott’s stories introduce protagonists who acquire supernatural powers and time-travel to a prehistoric village. In many of her stories, the settings of rural and suburban South Carolina — drawn from Elliott’s upbringing — contribute to the sense of magical realism. Heat, humidity, lush forests and cicadas that “blared like summer’s engine” help to blur the lines between real and supernatural.

“I have always been fascinated with genre experimentation from the very beginning of my writing, and so, I do remember as an undergrad reading Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Franz Kafka, Angela Carter, and all of them were playing around with Surrealism, fabulism, magic realism, all of that,” says Elliott.

Reflecting on her growth as a writer, Elliott credits University of South Carolina English and Honors professor Carolyn Matalene as being one of her early supporters. Matalene recognized Elliott’s promise as a writer and a thinker, looking past what Elliott refers to as “hyper-pretentious prose that had too many polysyllabic words.”

After graduating from USC, Elliott earned an MFA from Penn State University and a Ph.D. from the University of Georgia. She acknowledges that she went through a period in which her “prose became so purple and baroque and pretentious that I couldn't get published for, like, ten years,” but in her current work, Elliott’s voice cuts as sharp as alligator teeth and lures readers through a mix of genres and settings.

She attests that this style allows her to “voice things that are difficult to voice,” echoing the observations she made about the horror genre at age 12.

That’s the fun of horror, Elliott believes, which really isn’t so scary: The more you know about it, the more you become an insider, catching references between works and joining the conversation.

“The students become obsessed with that, too,” she says, “and then they bring in all this cool stuff I don’t know and share it with me. And then, you know, it’s contagious. People form communities around their love of horror films.”