Advancing educational equity for African-American children

How culturally relevant teaching techniques help students

Posted on: October 11, 2017; Updated on: October 11, 2017

By Kathryn McPhail, mcphailk@mailbox.sc.edu, 803-777-8841

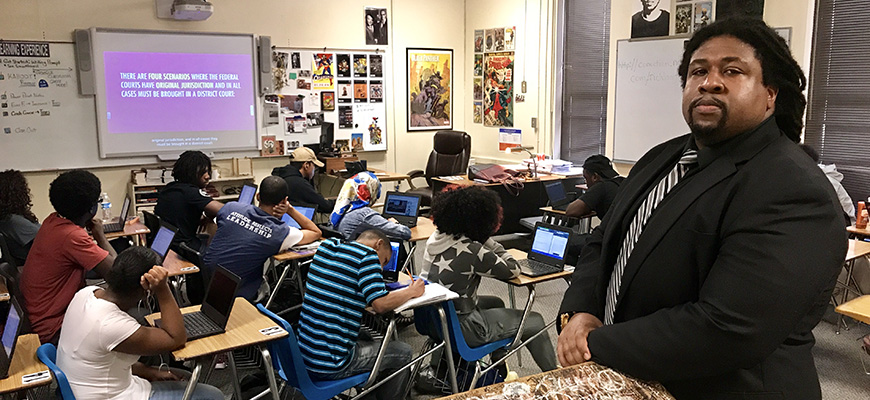

Rapping the words to the U.S. Constitution and reading about American government from the pages of a comic book might seem odd — unless you’re a student in one of Brandon Harrison’s classes at Richland Northeast High School in Columbia.

“I believe that, as a teacher, we must meet our students where they are to help them learn,” Harrison says. “To reach them, I use some unorthodox teaching techniques.”

Those unorthodox teaching techniques include embracing hip-hop culture when teaching government and economics.

“I give my students options for learning the standards. I’ve asked them to write lyrics to learn the preamble to the Constitution or the branches of the U.S. government. They love hip-hop, and I do, too, so I can use this to truly connect with them. Once they know you’re invested in their lives, they are more likely to invest in their studies,” Harrison stresses.

Today’s lesson — learning supply and demand by examining the sneaker culture.

“Our students love sneakers — some wear a different pair each day,” Harrison jokes. “So, I use the sneaker industry to teach supply and demand, explain the stock market or to introduce other important concepts. This connection helps them absorb the content in a way that’s culturally relevant to them.”

His culturally relevant teaching techniques and successes recently garnered the attention of educators within the Center for the Education and Equity of African-American Students (CEEAAS) at the University of South Carolina’s College of Education. The center was established in January 2017 to research, promote and achieve equity in teaching for black students.

“Our hope is to improve the lives of African-American students in South Carolina and beyond by making sure they are effectively educated,” says Gloria Boutte, center founder and executive director. "There are documented examples of schools across the country, and right here in our communities, that are effectively teaching African-American students — even students from lower socioeconomic statuses. So it can — and should — be done.”

Boutte, along with center director Jennifer Clyburn Reed and their colleagues at the center, is working with Harrison and two other public school teachers as part of a pilot program. The program is aimed at identifying which methods work best when teaching black students. They plan to use their findings to replicate and share the curriculum with other teachers and other schools.

“Through partnerships with public schools and numerous outreach programs, the center aims to improve academic and cultural outcomes for black students,” said Boutte. “By drawing from research about the most effective ways to instruct, educators can teach African-American students by using culturally relevant curriculum.”

The center also serves as a forum for community engagement by hosting numerous events that are free and open to the public including monthly roundtable discussions, book studies and conferences. The next roundtable is set for Oct. 19, and will focus on teaching African-America history. The event will be held 4:30-6:30 p.m. in Room 219 of the Child Development Research Center, 1530 Wheat St. Additional roundtable discussions will be held in November and December, as well as a conference for educators set for Jan. 18. A calendar of events is available on the center's website.

“Our center, with help of educators such as Mr. Harrison, advocates for African-American children and elevates the awareness of their needs, perspectives and voices,” says Boutte.