The University of South Carolina is focused on the brain. From Alzheimer’s and other related dementias to aphasia and autism, researchers are working across several academic disciplines to better understand how the brain works and to improve treatments for patients.

Demonstrating USC’s commitment, the university’s forthcoming health sciences campus in Columbia’s BullStreet District will include an emphasis on brain health. Plans include a Brain Health Center that will build on the university's McCausland Center for Brain Imaging. Already, the university has opened several clinics to improve diagnosis and treatment of brain-related conditions as part of a statewide Brain Health Network.

The university’s efforts are multifaceted, covering multiple conditions and emanating from many schools and colleges. Below, we take a look at the work of several USC neuroscience researchers, with a special emphasis on autism.

According to the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, one in 36 8-year-old children has autism spectrum disorder, with the incidence even higher among underrepresented minorities. So, it’s significant that researchers at the Carolina Autism and Neurodevelopment Research Center are working across multiple disciplines to gain a deeper understanding of what causes autism, how it can be treated and how it relates to other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Together, Jeff Twiss, associate dean for research and graduate studies in the College of Arts and Sciences, and co-director Jane Roberts, Carolina distinguished professor of psychology, have recruited faculty members with appointments in departments across the university, bringing into focus one of the center’s goals — tearing down silos and pulling together diverse research.

There’s Jessica Bradshaw, an assistant professor of psychology, who is researching early-emerging behaviors in infants in order to diagnose autism earlier and improve treatments. There’s Fabienne Poulain, an assistant professor in biological sciences, who studies the mechanisms underlying brain wiring during development. There’s Jessica Klusek, who studies fragile X syndrome. And many other researchers whose work helps inform our understanding of autism.

“We all do very different things and come from very different backgrounds and directions,” Twiss says. “Oftentimes we’re discussing and kind of arguing about things, and it turns out we are using different language to refer to exactly the same thing.”

The prevalence of autism among children is rising — but access to new, evidence-based intervention isn’t following the same trend. Sarah Edmunds, an affiliate scientist at the Carolina Autism and Neurodevelopment Research Center, is trying to change that.

“It takes about 17 years for an evidence-based intervention or therapy to make it from the research phase at a university to actually being available in any sort of clinic or setting that the average person might find,” says Edmunds, an assistant professor of psychology. “That’s not acceptable.”

In her current research, Edmunds is investigating several emerging therapies collectively called Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions. Her goal is to adapt them so they can be used to address individual children’s needs.

“I’m trying to improve and fine tune evidence-based supports and interventions for autistic children and adolescents and their families — and, through implementation science, I’m trying to improve access to those interventions to support autistic kids in actual community settings,” Edmunds says.

Ultimately, she says, what’s needed for implementation of new, evidence-based therapies is a scientific examination of what support is needed, whether it’s policy change, better training or other implementation support.

“We have to find the best methods for getting these interventions out into the world,” she says.

Fragile X syndrome is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability and autism. It stems from a gene mutation on the X chromosome. There is no known cure or specific treatment. The FMR1 premutation is the genetic mutation found in women who are carriers of fragile X syndrome.

In the United States, about one in 450 men and one in 150 women are carriers of the FMR1 premutation. Apply those rates to South Carolina, and one would expect about 24,000 carriers across the state.

Jessica Klusek, a USC associate professor of communication sciences and disorders at the Arnold School of Public Health, has been studying and advocating for children and families affected by fragile X syndrome for years. She and her team at the SC Family Experiences Lab are now collecting data on women in demographics who really haven’t been studied previously, hoping to gain a better understanding on age-related decline among women who carry the FMR1 premutation and whose children are diagnosed with fragile X syndrome.

“A lot of the research on aging in the fragile X premutation has just focused on men,” Klusek says. “I’m definitely getting more interested in fragile X premutation carriers, which in my program of research is specifically focused on women who are carriers.”

Most of what is known about women as carriers arrives from studies that were focused on children with fragile X syndrome. In many cases, the caregiver — who is most often the mother — would participate as a measure of family environment. But the mother was not the focus of the research.

“Because there’s so little research on aging in women who carry the FMR1 premutation, I don't think they're necessarily getting good clinical care,” Klusek says. “We need more research to guide this population and to guide health care professionals. That way we can raise awareness of preventative strategies and how to improve health with aging.”

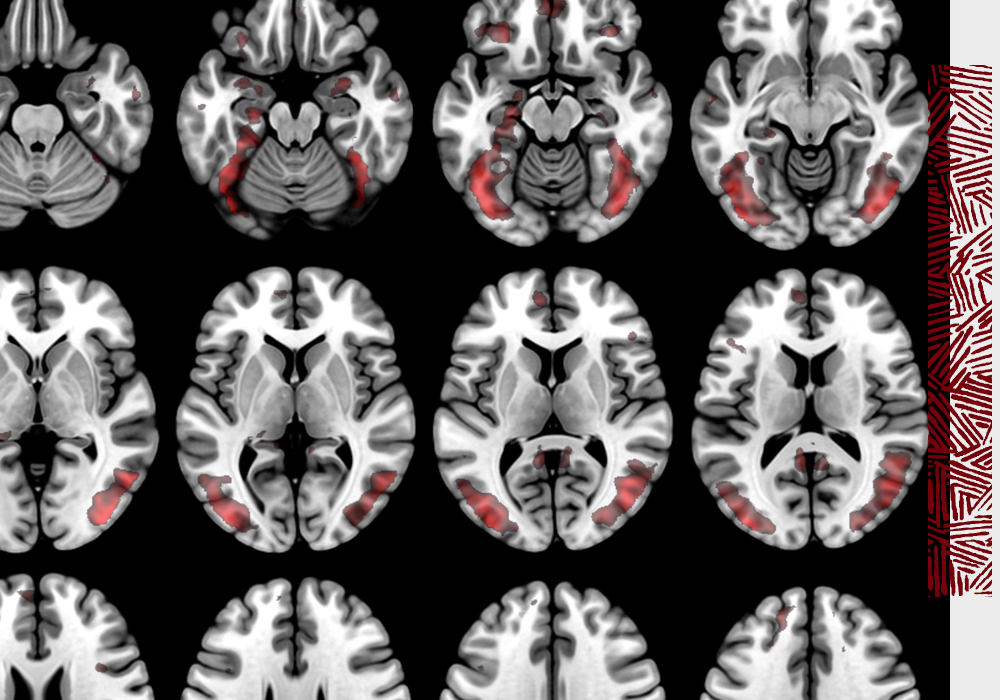

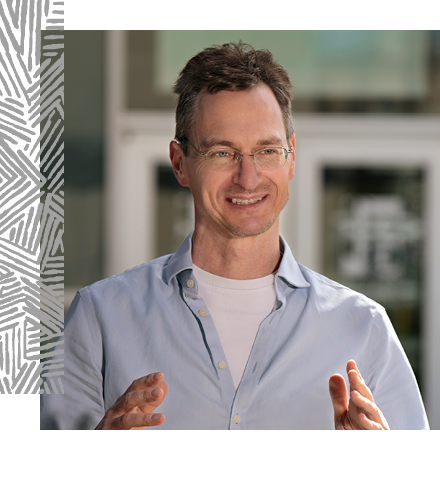

As a psychology professor and co-director of the university’s McCausland Center for Brain Imaging, Chris Rorden has made his mark with the open-source software he developed to assist in brain visualization, image processing and statistics.

“My seminal image processing work has allowed tools designed to look at the healthy brain to be translated to clinical applications,” Rorden says. “This has provided new insights on stroke recovery and helped guide brain stimulation.”

The visualization software has proven valuable throughout the field of neuroscience, and is used for understanding healthy brain function and for mapping the location and extent of brain injuries.

Dirk-Bart den Ouden, graduate director in the communications sciences and disorders department, says the opportunity to work with Rorden was one of the reasons he chose to come to the university. He calls Rorden a role model for mentoring and motivating others and praises Rorden’s talent in cross-department collaboration.

“He is open to hearing alternative views, gets excited about new ideas and can be relied upon to offer smart and creative solutions, as well as to actually do the work and implement such solutions hands-on, by writing code or building hardware,” Dirk-Bart den Ouden says.

Analyzing large datasets of heart rhythms and brain wave activity with AI and machine learning, a team of University of South Carolina professors is working to better understand autism spectrum disorder and identification of ASD diagnostic biomarkers.

Jessica Bradshaw and Caitlin Hudac in the Department of Psychology are collaborating with Christian O’Reilly, a computer science and engineering faculty member, to search for potential patterns and markers of autism spectrum disorder and more.

Identifying reliable biomarkers of ASD to diagnose the disorder soon after birth — as opposed to the current norm of diagnosing at 3-4 years of age or older using behavioral markers — would be a breakthrough, Bradshaw says, because it would allow much earlier therapeutic intervention. The researchers’ work could also help point the way toward differential diagnoses, which would allow children to get more tailored therapeutic approaches.

“It’s one thing to say, ‘I think that child falls under the broad umbrella of ASD,’” says O’Reilly. “But what if that umbrella was divided into subgroups — people who are on the spectrum for different reasons — that could be assigned the therapeutic approach that would best help them?”

O’Reilly’s AI and machine learning tools aim to better understand and differentiate the physiological mechanisms involved in ASD using data collected by Bradshaw’s, Hudac’s and other research groups at USC.

The research is challenging, Hudac says, and it will require a multidisciplinary approach.

“It is more involved, trying to make sure that the data we get is going to help us in that therapeutic sense,” she says. “I think it’s going to be absolutely pivotal, though, and no one field can make that happen alone — it’s going to be an exciting decade in ASD research.”

New drug therapies being tested for treatment of schizophrenia also hold potential for treating autism, says a School of Medicine Columbia faculty member who studies the brain receptors targeted by the experimental drugs.

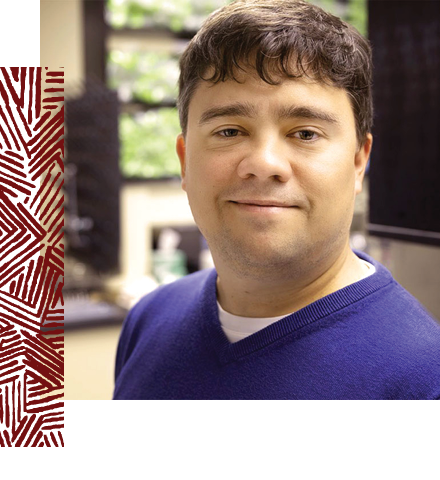

Daniel Foster, who joined the Department of Pharmacology, Physiology and Neuroscience in 2022, is using a National Institutes of Health grant to study the relationship between repetitive behaviors and a particular brain receptor linked to such behaviors. Foster’s research suggests that muscarinic acetylcholine receptors could be a prime drug target to treat the habitual behaviors often seen in individuals on the autism spectrum.

“It’s interesting to think about how a pharmacological therapy could fit in,” Foster says. “There are not a lot of studies on this, but could giving a drug targeting the muscarinic receptors prime the brain to respond better to behavioral therapy?”

One of the big draws of USC for Foster was its commitment to neuroscience and its collaborative environment.

“The focus of this university on expanding its neuroscience research was a real draw,” Foster says. “Integrating basic researchers with clinicians is actually more rare than people think.”

Scientists at USC’s School of Medicine Columbia are researching important links between brain mitochondrial function and social behavior.

“We're focused on the neurological underpinnings of social behavior and what happens when social behaviors are disrupted,” says Fiona Hollis, an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology, Physiology and Neuroscience. “We believe that brain mitochondrial function sits at the heart of that.”

Mitochondria organelles generate biochemical energy necessary for cellular function and play a vital role in immune activation, cell signaling and hormone synthesis, among other functions. Chronic stress can reveal the links between mitochondrial function and social behavior.

“Our research studies how brain mitochondrial function might modulate social behavior,” Hollis says. “There are a large number of case control studies where evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction is present in these patients [with autism], and it’s at a higher rate than you would find in the average population,” she says. “Mitochondrial dysfunction is not a core symptom of autism, but it’s certainly on the radar in the clinic.”

Hollis is an affiliate of the university’s Carolina Autism and Neurodevelopment Research Center, collaborating with clinicians from psychology and communication sciences and disorders. As researchers at the center work to identify autism spectrum disorders in children as early as possible, Hollis hopes her work can help.

“We’re hoping to identify potential biomarkers that would be useful for their clinical research,” she says.

Carissa Stevens’ twin sons are one big bundle of energy, but after their first birthday, it was apparent they were on two different paths. Elijah was meeting all the developmental milestones while Malachi was not. A battery of tests confirmed a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

“We didn’t know anyone who had children on the autism spectrum, and we didn’t have any resources,” Stevens recalls of that 2017 diagnosis. “We just didn’t know what was next in our lives.”

Then, Stevens happened upon a pilot study conducted by Robert Hock, a professor in the University of South Carolina’s College of Social Work. The study connected parents of newly diagnosed children with other parents who already had navigated the labyrinth of decisions that face every family with children on the spectrum.

The program has become a lifesaver for parents like Stevens.

“This program is designed to support families shortly after they’ve learned that their child is diagnosed with autism,” says Hock, who is an affiliate faculty member with USC’s Center for Autism and Neurodevelopment. “It’s delivered by experienced parents to parents to provide them with emotional support and help them understand what services are available and how to go about devoting family resources, time and talents to help their child have the best future they can have.”

Along with helping parents quickly become familiar with treatment options and other resources, the Autism Parent Navigator program promotes positive mental health for caregivers. Ultimately, Hock hopes that data collected from the study, including outcomes for the children and mental health markers for parents and family caregivers, will create a blueprint to launch similar programs across the country.

“We’re hoping our findings can become an evidence-based practice that could be used by non-specialized caregivers at parent support organizations in all 50 states,” Hock says. “It could result in far better outcomes than parents just trying to do it on their own.”