Carlina de la Cova’s recent research hit close to home. As she studied the remains of people who died in public hospitals and other institutions more than 100 years ago, she couldn’t help thinking about her grandmother, her mother-in-law and others in her life who have needed institutional care.

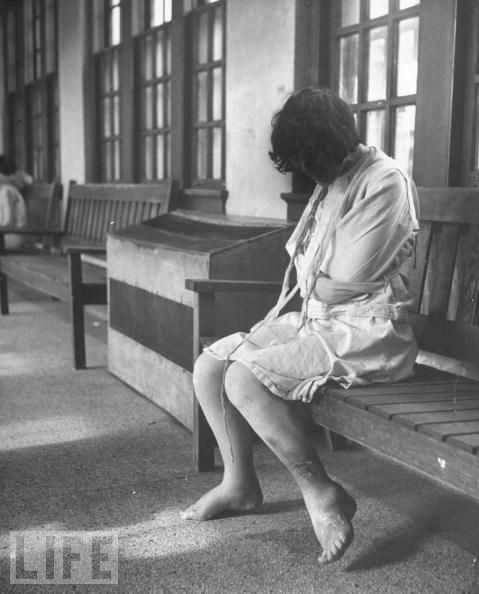

While her relatives received proper care, the people de la Cova studied clearly had not. They suffered broken hips and other injuries at much higher rates than people who were not in state institutions.

In an article published by Plos One, de la Cova and her collaborators shed light on neglect and abuse of marginalized patient groups. What’s more, she reveals that those same vulnerable groups continue to be at a higher risk for injury and death today.

“My aim is to raise awareness about these issues, so people know change is still needed,” says de la Cova, a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences. “We’ve come a long way from the institutions of the past, but our elders are still at risk for the same reasons. Social apathy for the elderly still exists.”

Evolving ethics

In her work, de la Cova and her collaborators examined life and death records of individuals born in the 1800s who lived in state institutions, including hospitals, assisted living facilities and nursing homes. They found that these institutions left patients at higher risk of injuries and death, and that this issue persists today.

“Structural violence in the forms of underfunding and understaffing continues to manifest as hip fractures harming institutionalized individuals today,” de la Cova writes.

This led her to seek answers to the question: can factors from the past be tied to patterns of today?

To find out, de la Cova turned her attention to bodily remains in the Robert J. Terry Anatomical Collection, housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Over a third of these individuals died in state institutions.

De la Cova examined the remains of 600 individuals born in the 1800s, looking for evidence of hip fractures. She studied historical articles and news reports about any injuries the individuals sustained while living in state institutions and compared the data to injury prevalence in individuals not living in state institutions.

Her findings showed that people in institutions suffered broken hips and other injuries twice as often as the others, with injuries in post-menopausal women being most common.

She also found that the institutions were overcrowded, understaffed and in dangerous disrepair. Loose and missing floorboards created fall risks and metal railings fell on patients, among other examples. In extreme cases, patients were forced to go without food, clothing and other necessities.

What’s more, de la Cova says that social apathy towards the mentally ill and elderly made these issues go below the notice of governing bodies who could have intervened, resulting in little to no legislative change for years.

Eventually, nursing homes, smaller clinics and assisted living facilities replaced many state institutions to care for vulnerable populations. However, many are plagued with the same issues as their state-based predecessors, de la Cova says.

Despite the ongoing issues, anthropologists are making some promising progress in the way they honor the humanity of the individuals who’ve made research like de la Cova’s possible.

For example, since de la Cova conducted her study in 2022, the Smithsonian has halted scientific research on the Robert J. Terry collection. That’s because anthropologists are grappling with the ethics of studying the remains of people who did not consent to be studied.

Many institutes, including the Smithsonian, have begun evaluating the human remains in their care to determine which of those remains should be subject to ethical return or shared stewardship. Because the individuals died in state-funded institutions, their bodies were presented to the state anatomical board to be used in study. They were “anatomized.” Names were replaced with cadaver numbers.

“Not only were they not cared for in life, but they didn’t have the things that most of us take for granted, like the ability to choose what happens to our body when we die,” she says.

“My approach has been to tell the stories of these individuals; how did they end up in these collections? My aim has been to force the discipline to confront that history and to restore the humanity of these individuals by telling their stories.”

De la Cova has spent her career studying the individuals in these collections, and newer generations of scholars have started building on the research approaches she started.

Moving forward, de la Cova hopes to use what information is already available from collections that are being rightfully repatriated. She says it’s important to continue to learn from their stories and bring awareness to ongoing issues of institutional neglect.

She hopes her research on the lived experience in institutions of the past will drive public policy to “entrench the equitable care of institutionalized people as a human right” while also investigating the social origins of anatomical collection and the stigma of dissection.

Just as her experience putting her mother-in-law in a nursing home brought her research home, de la Cova deeply identifies with those, past or present, who have who died while in state care.

“Every time I do my work, I think about my granny who went up to Chicago, during the Great Migration, to obtain training in nursing,” says de la Cova. “Had she died in Chicago, with no family to claim her body, she could have very well ended up being anatomized.”

“As an anthropologist it’s always been important to refer to the dead as people and to treat them how you’d treat a grandmother.”