Tanya Wideman-Davis and Thaddeus Davis are used to living out of suitcases. As professional dancers for several decades, traveling for performances comes naturally. Recently, however, they’ve unpacked more than just their suitcases in their home for the last 9 months, Montgomery, Alabama.

The duo are deconstructing their understanding of Black history in the South and using dance to reshape the way stories of Black life have historically been portrayed.

Associate professors in the departments of Theatre and Dance and African American Studies, Davis and Wideman-Davis are conducting this research as part of a grant from the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project.

The award enables them and their dance company, Wideman Davis Dance, to live and work in three different cities for a year each. During the year, they dance, teach and engage with the community, while continuing to evolve their interactive performance series, Migratuse Ataraxia. After completing their project in Montgomery, they will have a residency in Harpersville, Alabama, before bringing the project back to Columbia.

We spoke with the professors about their monuments project and what’s next for them as researchers, teachers and performers.

What is Migratuse Ataraxia and how did it first originate?

Davis: The performance examines, explores and expresses the humanity of enslaved Africans’ existence in antebellum plantations. When we developed the concept in 2016, we were thinking about Black life despite bondage, the architectural spaces that Black bodies moved in, and the restrictions and spaces of resistance inside of plantation existence. We premiered Migratuse in Harpersville, Alabama, at the Wallace Plantation.

How does the theme of “monuments” fit into Migratuse?

Davis: The plantation is a monument – to enslavement, to southern existence, to whiteness, even though Black bodies were the laborers on those plantations. The Monuments Project came into our purview in 2019. We hadn’t thought about these [plantation] spaces as monuments, but when we started using that language, we realized that we were memorializing the old South in many instances.

Wideman-Davis: A monument can also be an archive of the body — what gets transferred from body to body and what gets archived in the body that can then be presented. In that way, the dances and the dancers are monuments themselves.

Your monuments project involves different components, including living in a new city each year for three years. How did you develop the structure for this project?

Wideman-Davis: Traditionally, dance companies will tour in a city for a week, and then leave. That was not the template we were interested in doing; we wanted to connect with and create with community by curating experiences that the community can be a part of.

Davis: The Mellon grant allows us to spend a year in three different locations. We bring our entire team of artists and collaborators to work in community, hold conversations and host artistic and intellectual ideas. We also create fellowship opportunities for local artists who create works that will have a loose thematic focus around monuments.

How did you begin the historical research that informed your approach to this project?

Wideman-Davis: We started looking through the Alabama Digital Archives where we came across images photographer Jim Peppler took for the Southern Courier. There were photos of the Civil Rights Movement, but also Black life in social settings and doing everyday things. The images gave us insight into what Black life was really like in Montgomery in the ’60s.

During that time period, the narrative gets trapped in the Civil Rights Movement as if Black folks weren’t doing anything else. We were getting to see Black folks from the ’50s as ’60s as actual people. They fought for those rights because they had such rich lives in their own environments. That’s a privilege we’ve been able to have – highlighting the mundane experiences of Black life.

In what ways did those images affect how you choreographed this iteration of Migratuse Ataraxia?

Davis: We’re making theatre that reflects life and allows access for people to see themselves in the movement and the work. In looking at these frozen human forms in a moment of pleasure, we’re left to imagine what happened before and after the framed shot. We’re looking to bring that movement back to life. The way those bodies moved in the ’70s probably wasn’t much different to how we move today. These cities have such a distinct narrative, and the production supports people having access to seeing themselves being portrayed.

Wideman-Davis: Montgomery was speaking to what timeframe our work needed to be in. These cities have such a distinct narrative, but it’s also this trapping of a time period that Montgomery wants to move forward from. We can look for futurity, we don’t have to stay in the past.

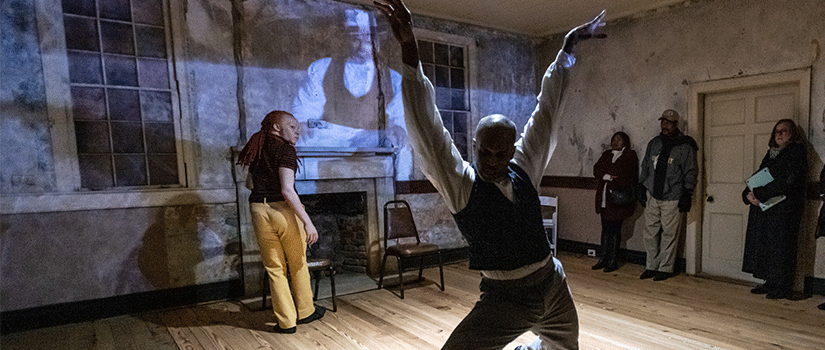

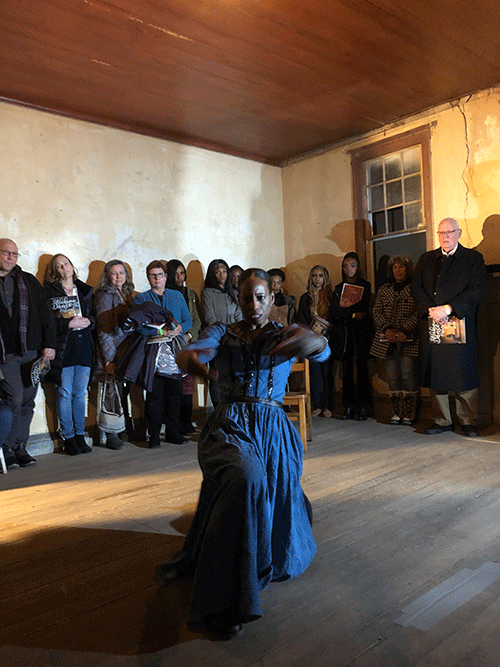

Migratuse is performed in intimate spaces where the audience surrounds the performers. How does this differ from a traditional theatre or dance performance?

Wideman-Davis: You’re getting a close-up experience where the dancers might pull you out or take your arm to lead you to the next sequence. Audience members can get overwhelmed with emotions because of the proximity, and they are a part of it. The dancers see each person’s eyes, and each audience member can look the others in the eyes. This witnessing is important because it opposes what used to happen in these places, which is surveillance. As a performer, there’s a different kind of labor that goes into it. You’re taking on your emotionality of performing and that of the audience.

How does the performance change by leaving a traditional theatre environment?

Wideman-Davis: We have more leeway to curate who comes to these performances and create the possibility of allowing African American audiences. It democratizes who gets to see these performances, when we’re allowed – through this grant – to engage Black communities.

Davis: It doesn’t mean the rest of America isn’t invited, it just means we want to reach a specific audience. This is about letting Black people see themselves in a performance environment. We want to celebrate the beauty of the mundane existence of Black life. That’s why we needed to take this piece out of the theatre.

You have USC alumni collaborating on this project. Tell us about their contributions.

Wideman-Davis: Petra Everson and Michael McManus are traveling with us. Building site-specific performance requires openness and the ability to contribute to a larger group effort. Their interest in dance builds community through research and historical investigation and gave us the confidence to hire them as professional dance artists. It’s an amazing opportunity to have our former students on the project. Opening doors like this is the epitome of what a dance degree should yield physically and intellectually, and we are excited to have them among the eight interdisciplinary artists we collaborate with and employ.