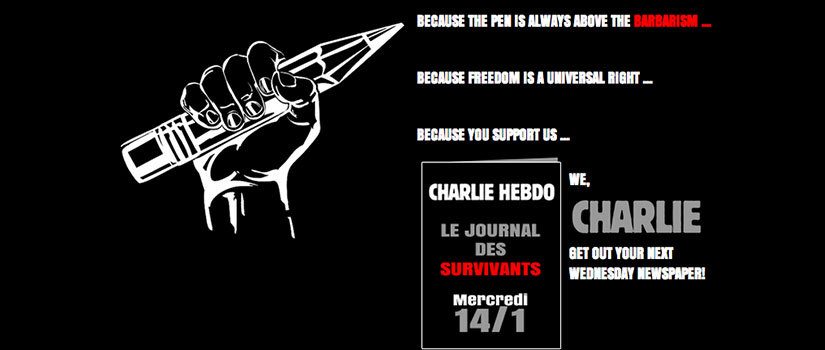

Image: Charlie Hebdo's website announces it will publish the next issue on schedule.

Posted Jan. 12, 2015

By Charles Bierbauer, dean of the College of Mass Communications and Information Studies

Journalists did not need the atrocity of the attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris to know that ours is a risky business. But it has made the rest of the world aware of the price of exercising free speech.

The combat correspondent is almost legendary. Ernie Pyle died from a sniper's bullet in a ditch on Ie island during the battle for the Pacific in World War II. I've lost friends and colleagues in wars and conflicts in Iran, Nicaragua and Bosnia. Don Bolles, a founder of Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) was murdered in Arizona with a car bomb. Victor Riesel, a crusading columnist, was blinded by acid when attacked on a New York street.

But cartoonists? In their office? In Paris?

We should not be too surprised. The pen, pencil or digital stylus is a rapier, sharp

and piercing. It can sketch a comic caricature or craft a grotesque image, each capable

of skewering a target of derision or disdain. Charlie Hebdo's cartoonists pierced

the thin skin of the terrorists who attacked them, whether for religious revenge or

political pretense.

We should accept that many careers are inherently risky. The military, first responders,

long-haul truckers and airline pilots have actuarial risks. In our recreational pursuits,

we routinely sign waivers acknowledging that whitewater rafting, horseback riding

or skiing may result in death. The fine print on our medications — though we hardly

ever read it — says death may be a side effect.

There's no fine print on the side of the pen. The Charlie Hebdo cartoonists knew what they were doing. Call them satirists, practicing political commentary, a cherished tradition of journalism. It can be biting, whimsical, laugh provoking, while conveying a message more pointedly than these 700-some words.

Political cartoons are meant to convey an emperor-has-no-clothes message. We get the point. Politicians often ask the cartoonist for signed originals of the cartoons that mock them, then hang them proudly in their offices, no matter how blistering the cartoon's criticism. They don't hang critical columns on those walls. Ask a politician about his or her "me wall" sometime.

That's not the case in rancorous, humorless societies. Charlie Hebdo's editors would have known that when Jyllands-Posten published cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammed in 2005, it led to death threats.

I can't draw a stick, but when I was the ABC News correspondent in Moscow in the late 1970s, I had cut out some cartoons mocking the Soviet Union and tacked them to the bulletin board behind my desk. I received a summons to the office that controlled foreign journalists and was told that my cartoons offended the Russian staff working in the office. Since I depended on that staff, I took them down. But when my reporting offended Soviet officials, I took my chances. The worst, I figured, was that I'd be expelled. The worst I got was being roughed up, arrested and released.

Yet other journalists have gone to prison for what they've written. Or what they've refused to reveal, such as who their sources are. That's happened here in our country.

Intimidation and harassment are often the weapons deployed against the journalist. It can be physical, though it is more often psychological. Cops do it — "you can't go in there." The military does it — "turn in your credentials." Corporate lawyers do it — "we're going to sue you." Politicians do it — "you're out of business with me."

But that's all punk stuff that comes with the territory. When Ronald Reagan's White House spokesman Larry Speakes declared one of us "out of business," we wore it as a badge of honor and called our better sources.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo, in contrast, is a red alert. The world's cartoonists have responded in black and white, in some cases in blood red, to show solidarity with the Paris victims.

It's a t-shirt and bumper sticker slogan, but it's true. Talk is cheap. Free speech isn't.

![]()