For Kirsten Fisher, the world of plants is a world of wonder. But it’s not without danger. Indeed, it’s a world in which herbivores, diseases, weather and machines can and do cause injury and death every day.

What wasn’t understood until about 40 years ago was that plants haven’t been dumb to those dangers. With their own chemical language they warn each other about impending harm and actively defend themselves from it.

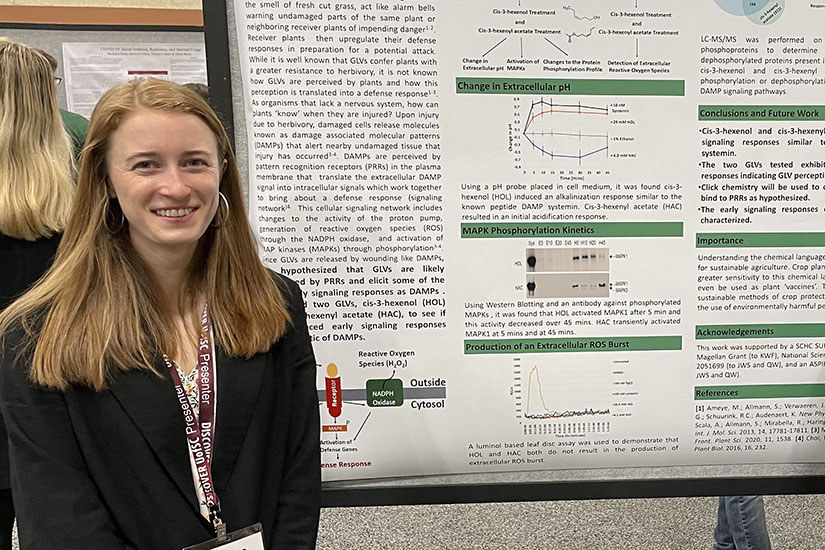

“When you cut your grass, that smell is of plants crying for help,” Fisher said, explaining how blades of grass, when clipped – or wounded – release green leaf volatiles into the air. Those GLVs are recognized by neighboring plants, which can then prepare their defenses for an attack. How those plants perceive GLVs fueled three years of her research as a biochemistry/molecular biology student in the South Carolina Honors College. And it brought her the 2023 William A. Mould Senior Thesis Award for her 54-page thesis, “Deciphering Green Leaf Volatile Perception in Plants.”

“Kirsten is the top undergraduate researcher I ever mentored among 57 students, including another Goldwater Fellow, a professor at a research university, and many medical doctors and dentists,” wrote biology professor Johannes Stratmann, Fisher’s thesis director, in his nomination letter for the award. “Her analytical and trouble-shooting skills are highly developed. She comes up with her own ideas for how to improve experiments or how to interpret the results in the context of the overarching project.”

Funded by the family of the late William A. Mould, a beloved cofounder of the SCHC, the thesis award recognizes research most likely to have a broad impact on the student’s field of study. Stratmann attested to that possibility, writing that Fisher’s research “could lead to new strategies for sustainable agriculture.” Her fundamental research with tomato plants could one day be translational as scientists learn to engineer crops that can better withstand a warming climate and fungal or bacterial infections.

“My thesis characterized the early signaling responses induced after GLV perception, and also if there’s a certain motif or portion of the volatile that’s necessary for perception,” Fisher said. “It points to (the fact that) there might be an actual GLV receptor in plants. We’re not entirely sure, but the work of my thesis does help further disentangle the GLV perception mechanism, and that’s really big.”

A Sumter native, Fisher’s curiosity about plants flourished under Hugh Hill, her biology teacher at Wilson Hall. Hill had been a student of Wade T. Batson, the legendary South Carolina botanist and University of South Carolina professor. Class field trips during which plants and flowers were identified and studied became favorite times for Fisher, a National Merit Scholar and Palmetto Fellow who was awarded a Provost Scholarship to attend USC.

Though disrupted by the Covid pandemic, Fisher’s time at USC was anchored by her steady research with Stratmann, which was supported by an NSF-EAGER grant. She was awarded the Goldwater Scholarship in 2022, something she says wouldn’t have happened without the guidance and encouragement of Novella Beskid, the recently retired assistant dean for National Fellowships and Scholar Programs.

Fisher’s next stop is the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she’ll pursue a Ph.D. on her way to a career as a university research professor. She chose UW because of its reputation for collaboration among departments. Her own research benefited from the cross-disciplinary work she did in Stratmann’s lab with Qian Wang, a professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry and second reader for her thesis.

“Cross-disciplinary research was a monumental part of my undergraduate research experience. I wouldn’t have done half of what I did without Dr. Stratmann and Dr. Wang. My mentors at UW will have big shoes to fill.”

While she’s not certain about where she’ll land – though she knows she wants to do her post-doctoral research at a Max Planck Institute in Germany – she is certain about what she’ll do.

“I really want to study and understand the biochemical mechanisms that plants use to thrive in diverse environments and harness these mechanisms to make more resilient plants,” she said. “Plants have evolved unique biochemical pathways that produce specialized defense compounds in response to various stressors, and I’m open to studying any of these pathways to gain insight on how to improve a plant’s stress tolerance.”

Meanwhile, she’s working on a second journal article spawned by her research – her first is published under the preprint server bioRxiv – and preparing for a colder climate in graduate school. And she’s tending her own plants, ever curious about their nature and history, and the human connection to their mystifying, little-known universe.

“I think it’s fascinating that for so long people thought plants were just these sessile organisms that sit there and grow and produce flowers, but there’s this whole other world of plants,” she said. “I think there’s a lot we still don’t know.”