Posted June 11, 2019

By Ernest L. Wiggins, Associate Professor

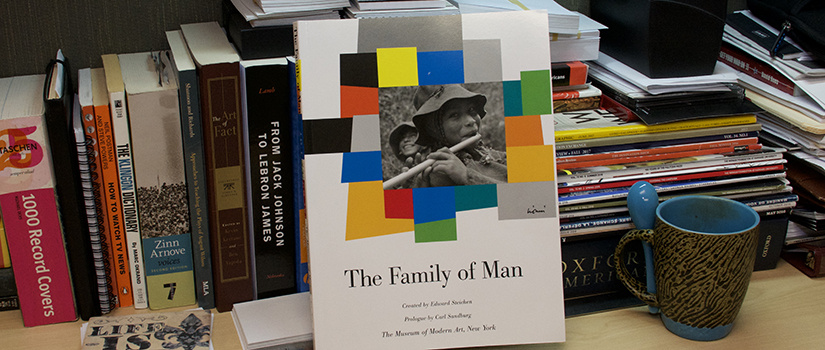

When I was a child, quiet Sunday afternoons often meant taking a trip around the world by leafing through a copy of Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man, the published volume of his exhibition of photographs that opened at The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1955.

I never saw the actual show, and I imagine most people who have pored over the book’s 200 pages in the past 60 years never saw it either. I am also certain those fellow travelers were transported as I was by the photographs Steichen curated for the show, which would eventually tour the world.

As Steichen writes in the introduction, “It was conceived as a mirror of the universal elements and emotions in the everydayness of life — as a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world.”

For a boy of 10, unfamiliar with the ways of the world, discovering these photographs of amateur shutterbugs and famous photojournalists was an early lesson about our shared humanity. Sure, I thought some of the costumes and locales were peculiar but they were also enticing. I remember thinking often, “I’d really like to go there!” Greece, Indonesia, Australia, Germany, Brazil.

The more I visited, the more I recognized the familiar in these photographs from North America and every habitable continent. Without the use of air or rail, I was on an African savanna, in a crowded South American night spot or in the midst of an Asian marketplace. The pictures communicated to me like today’s Instagram or Snapchat postings but maybe with more purpose, less caprice. Because the photographs were captionless, my imagination filled in the narrative gaps.

Nina Leen’s picture of an American farm family posed beneath framed portraits of patriarchs and matriarchs assured me that the world is made up of close kin, like mine, who shared common features, in this case markedly pronounced ears on the men. But that family was not so different from fellow Life photographer Nat Farbman’s striking image of another family taken in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and displayed on the facing page. In this family, some of the women and children had painted their round faces and gathered about the father, who looked intently at the camera, a smile of pride or contentment on his face. Both photographs featured an elderly matriarch because ALL families take care of grandmother.

I was captivated by George Rodger’s photograph for Magnum of 20 tribal women and children in French Equatorial Africa (now Chad, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon), the women’s bodies covered in printed wraps, all walking single-file, woven baskets on their heads, a heavy sky of threatening clouds above. My young mind wondered where they were heading and if they got there before the rains came.

A Bolivian woman in signature bowler hat was photographed by Gustav Thorlichen in what appeared to be a quarry, a mallet lay idle at her side, an infant at her breast. I suppose I was first stricken with surprise that she was ALLOWED to bring her baby to this place and then with pity that maybe she HAD to bring her baby with her. How miserable her life must be, I thought. Today, 50 years later, I look at the photo and wonder what became of the child and if memories of the quarry lingered.

Though I was much too young to vote when I first saw them, I was inspired by the quadriptych of photographs by Dmitri Kessel, John Florea, Eastfoto and Herman Kreider of citizens casting election ballots in France, Japan, China and Turkey, respectively. Although today the political message of this juxtaposition is apparent, as a child I simply thought this practice — voting for the country’s leaders — brought nations together. It was what the world did.

And Al Chang’s haunting photograph of an American soldier comforting a weeping comrade, members of the U.S. Signal Corps in Korea, told me then and reminds me today that something else nations do — fight wars and grieve.

I’ve brought this habit of studying photographs into my classrooms. I assign snapshots from The Family of Man or works by the likes of Dorothea Lange, Diane Arbus, Gordon Parks, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Eddie Adams to my students and ask them to write a 25-word statement that responds to it. “What does this photo say to you? What is the story? What question does it raise?” Like the photos themselves, the students’ responses never fail to surprise.