UPDATE: Since this article was written for InterCom, the research project has been the recipient of several national awards, including the AEJMC Creative Research Award in Design as well as the Faculty Best in Show (VR/AR/360 video) for the Broadcast Education Association On Location conference.

Decades ago, it would have been outlandish to think about getting a lifelike experience of Rome viewed from the 1700s. Outside of art or literature, there wasn’t a way of getting in touch with Italy, or really anywhere, in their past forms.

However, technology today has created a way to experience far-away, fantasy or historical experience from almost anywhere: using virtual reality.

Jason Porter, an instructor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications, and his research team received the Aspire II grant and used a combination of VR and USC library records to re-create 18th-century Rome from the eyes of a classical Italian artist.

The idea started from the research of Jeanne Britton, curator, Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, on Giovanni Piranesi.

“USC has the entire [Giovanni Piranesi] collection, one of the few places in the world with the full collection, and [Britton] has been poring through these volumes and digitizing them in order to make them more accessible for folks who don’t have the full set,” Porter said.

As they discussed Britton’s digitizing project more, Porter realized that there was potential in reviving Rome through Piranesi’s image beyond just the records.

“What’s really cool about his illustrations is that they had depth to them,” Porter said. “They were full with people, with animals, with a lot of environmental elements that made the illustrations feel alive.”

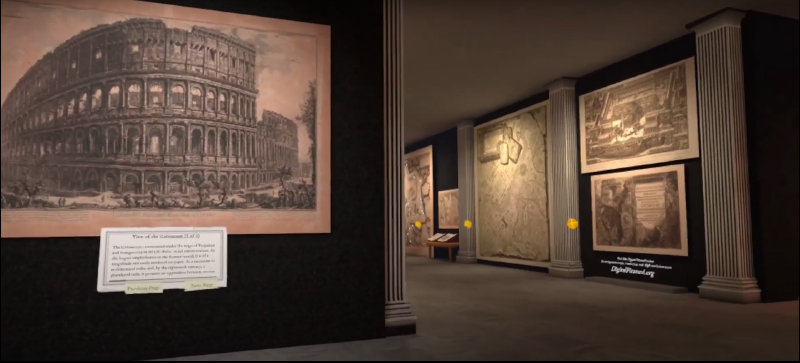

Inside the VR museum displaying Piranesi’s artwork. Each work had a narrated, interactive script for players to learn more info from.

However, Piranesi added his own spin to his work in addition to re-creating the city.

“[The art was] all kind of fake, they’re just based on reality,” Porter said. “He took his artistic license and made things seem bigger, or taller, or put these massive things closer together to make the composition of the illustrations feel much grander than they were.”

Porter, coming from an advertising background, saw Piranesi as an “advertiser” who was getting people in the 18th-century to come explore Rome.

Britton’s prior research, which Porter described as finding Piranesi’s “early examples of hyperlinks” left in the form of footnotes throughout his works that led to his other pieces, as well as the warped reality displayed in the art, led Porter to utilizing VR as a medium of displaying USC’s collection.

“If Piranesi wanted us immersed in these things, making up these spaces by putting things closer together and making things bigger and larger than they were, why don’t we make a VR scene that allows you to go into the world that he created?” Porter said.

Porter, Britton and Evan Meaney, a USC professor in media arts, wrote the proposal for the Aspire Grant II.

“The Aspire II grant is an internal grant awarded to folks who are developing interdisciplinary projects with different colleges,” Porter said.

VR re-creation of Piranesi’s Pantheon. Each letter represents an annotation left by Piranesi, close to the same spots that they would have been found in his artwork.

The professors used the grant to make a VR game where users were able to travel through Piranesi’s world. However, it did not just stop at the visual re-creation.

“Not only could you go into his world in this VR space and explore what he would have made, you’re also going through all of his annotations to figure out where, how, was the Pantheon made,” Porter said.

“Scholars debate it all the time, so we figured, ‘Let’s let other people debate it, and depending on the 26 annotations hidden throughout, it’s up to you to figure out your own opinion’.”

Controls used to navigate the VR game exploring Rome.

After working on the game through the latter half of 2022, Porter and team have completed the game and await USC approval to showcase it on VR stores.

Porter says that while the project was more of a hobby-like experience for him, he hopes to take his knowledge and apply it to future classes looking to use VR technology as a means of displaying information more interactively.

“The future jobs with VR are developing,” Porter said. “When we can then translate what we’re doing and help students develop prototypes for virtual and augmented reality experiences, that would be the goal.”