Posted February 12, 2018

Valerie Bauerlein, this year’s Baldwin Business and Financial Journalism lecturer, is a national reporter for the Wall Street Journal. She writes about small-town America and Southern politics, economics and culture. Before joining the Wall Street Journal, she spent four years as a reporter with The State newspaper.

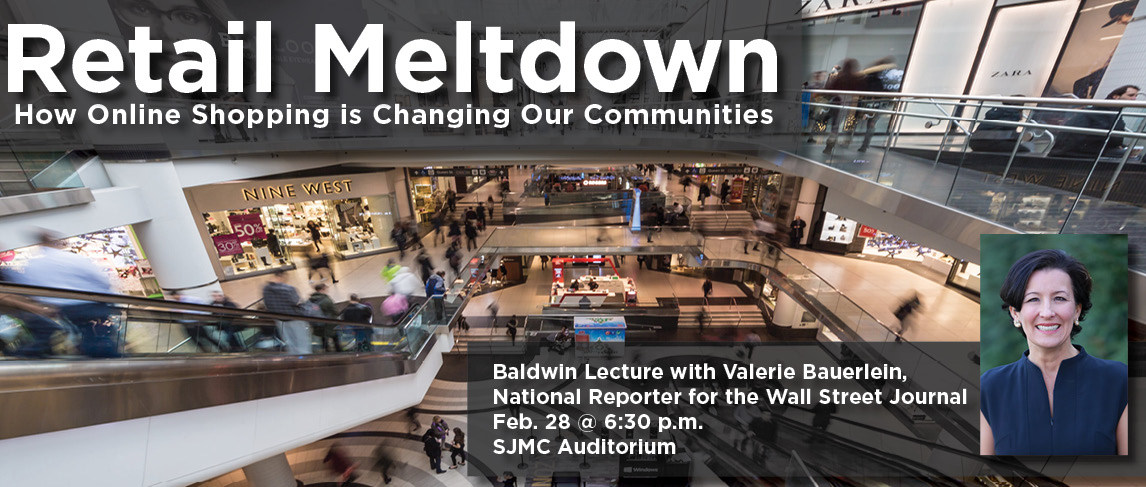

Bauerlein will explore the disruption in retail and how the acceleration in online shopping ripples out into the places we live in her talk, “Retail Meltdown: How Online Shopping is Changing our Communities.” The lecture, which is free and open to the public, will take place Wednesday, Feb. 28, at 6:30 p.m. in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications Auditorium.

We caught up with Bauerlein to ask her about the future of retail locally and nationally.

Consumer trends are changing, and it’s not just large corporations that are suffering. The collapse of traditional retail is also being felt in small-town America due to the loss of sales-tax revenue and retail-sector jobs. What kind of long-term economic impact are communities going to see?

Last year I went to Elmira, New York, and Wausau, Wisconsin, to report on the ripple effects of the collapse of retail. What I saw there is not so different than what is happening at shopping centers in Columbia and in lots of other places.

Elmira used to make everything from typewriters to TV tubes. As manufacturing went away, the mall out by the interstate became a bigger and bigger driver of the local economy, drawing people from miles away and employing hundreds of people. The local governments became dependent on sales tax to offset property tax and other revenue as manufacturing declined. So when the mall started to fail, people lost their jobs and became more dependent on public aid. And the city had become so reliant on sales tax to make its budget, it had to make deep cuts, even in its police force. There are lots of communities like this, who are dealing with the death of a big mall or outlet center that has been an anchor for the economy.

Wausau, on the other hand, is a prosperous place, by some measures the most middle-class community in America. The mall is failing there, too, in spite of being the only one in a 70-mile radius. In Wausau, the city didn’t need sales tax to make its budget and the local governments could absorb the decline in property taxes from the mall and other shopping centers. The big worry there was the death of what had been a community gathering place, and how to get new life into a building that was in the center of town. The other issue was how to support small shops in the downtown, so the people would want to live and work there.

So there are fiscal and civic ripple effects to our communities from the collapse in retail that are fascinating and often overlooked.

Malls used to feel almost like their own cities within cities because they had so much to offer beyond just shopping. Going to the mall was something people did for fun. But now, malls are dying or they’re being repurposed. Do you think malls — as we knew them — will ever make a comeback?

One statistic really stood out in reporting these stories: more stores closed last year than during the height of the Great Recession. Some analysts say there is still way more retail space per capita than we need, and hundreds of malls could close in the next five years.

Now it isn’t universal. High-end malls in some places are thriving. They tend to be in growing and wealthy communities, and most of them offer a lot of things to do, from classic mall activities like going out to eat or to the movies to newer concepts like having a gym or even apartments.

Other malls are surviving because they fundamentally change. People are saying, hey, we have a big building in the middle of town and we need to make sure it goes to good use. In Columbia, for example, the county commissioners are trying to put government offices in the old anchor stores at a mall. In Cleveland, Ohio, there’s a mall that used to be the biggest in the United States. Now it’s an Amazon distribution center, which makes sense when you think about what a mall has to offer: lots of parking, big open interior space, proximity to population centers, access to highways.

So there will be malls but there will be a lot fewer of them and they will look a lot different.

How does South Carolina compare to other parts of the U.S. when looking at the retail meltdown?

South Carolina has some buffer because it is a fast-growing Southern state, and the growth in population hides some of the stagnation in traditional retail spending and employment. The population has grown 13 percent in the past decade but retail employment is up only slightly in that same time. Retail employment is strongest in coastal towns like Charleston and Myrtle Beach, but is struggling elsewhere, like the Upstate.

The state budget writers say they expect to see sales tax growth continue to lag inflation and population growth. They also expect revenues for this current fiscal year to come in about $46 million less than expected, with $22 million of that miss coming from sales and use tax. That’s enough money to buy 200 school buses. There’s going to be a lot of pressure in the system over how to deal with the slowdown in sales tax collection without raising other taxes.

Before joining The Wall Street Journal, you spent four years here in Columbia as a reporter. Tell us a little about your time in Columbia and how that experience prepared you for what you’re doing now.

South Carolina is a big part of me. I covered the State House for The State in the early 2000s, which my old colleague John Monk says was the best job in journalism ever, except maybe covering the Kremlin during the late 1980s. Maybe. And I have always thought he was right.

This was in the days before social media, so the morning newspaper was hugely influential. You couldn’t go on Twitter to release statements, so we were really the place to make sure your voice was heard. On the politics team, I worked closely with some of the best journalists I have ever known, including Lee Bandy, who wrote a column for The State for ages. People didn’t always love what he wrote, but they trusted him to be fair. I loved to listen to his calls because he had a way of drawing people out and really listening to them. He taught me that the most important part of being a good journalist is being a good person.

I covered the budget, so I learned to read financials to find stories. I learned that there is almost always someone who knows the answer, you just have to find them. I also learned the merits of what we at the Journal call “no surprises journalism.” It’s really important that you make sure anyone mentioned in a story is prepared for what is going to be said, and has a chance to comment. That’s important everywhere, but especially somewhere like South Carolina, where politics is a pretty small world and you to need to maintain relationships over the course of years.

I always enjoy reporting in South Carolina and am always on the lookout for stories there. A couple of years ago, I realized my life’s dream of writing a page-one story about the Gaffney Peachoid. Next up, South of the Border!

About the Baldwin Lecture

The Baldwin Lecture Series is funded by the Baldwin Business and Financial Journalism Endowment, given by Kenneth W. Baldwin Jr.

A 1949 graduate of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications, Baldwin funded the endowment in 2009 to equip students with a depth of knowledge to investigate and report on the most significant and complex business and financial topics that affect consumers and taxpayers.

For more information on the Baldwin Business and Financial Journalism Lecture Series, contact Rebekah Friedman.