Individual state funding for substance use disorder declined by an average of $10 million per year during the 10-year period following the Medicaid expansion that began in 2010.

September 6, 2023 | Erin Bluvas, bluvase@sc.edu

Individual state funding for substance use disorder declined by an average of $10 million per year during the 10-year period following the Medicaid expansion that began in 2010, according to new research led by health services policy and management associate professor Christina Andrews. Published in Health Affairs, the team’s examination of state-by-state funding also revealed that allocations to the treatment of substance use disorder can vary dramatically – ranging from $0.61 per person in Arizona to $51.11 in Wyoming in the same year (2019).

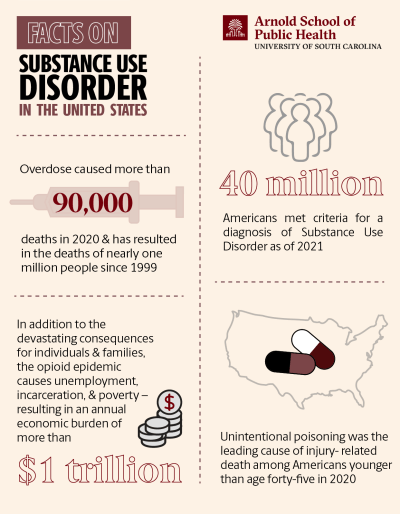

“The U.S. continues to grapple with opioid overdose and deaths, and Medicaid expansion is intended to help fight epidemics like this one,” Andrews says. “However, many states have shifted the financial burden for financing treatment programs from the state to the federal level, eroding the broader, system-level efforts that are urgently needed to address this nationwide problem.”

Individual state funding for substance use disorder declined by an average of $10 million per year during the 10-year period following the Medicaid expansion that began in 2010.

Support for programs like substance use disorder treatment and prevention (known as Single State Agencies) come from several sources, with Medicaid providing approximately half of the funding. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act significantly expanded access to Medicaid coverage to participating states – reducing the number of uninsured Americans from nearly 50 million (2010) to 20 million (2016) in just four years.

State legislatures allocate the remainder of the agency funding from state sources during the annual budgeting process. These state funds represent one quarter of all funding for Single State Agencies and are the largest source of funding (40 percent) in the handful of states (including South Carolina) that did not expand Medicaid. Andrews’ study found that legislatures in expansion states reduced state funding for substance use disorder programs by 10 million dollars per year during the period following Medicaid expansion.

“Medicaid expansion has triggered a dramatic infusion of much-needed funding into the substance use disorder treatment system,” Andrews says. “However, this funding is restricted to supporting reimbursements treatment of individual patients and cannot finance infrastructure demands, such as additional facilities and staff. Despite the limited parameters for using these funds, the increase in federal funding may have influenced states’ decisions to cut their own funds for substance use treatment and prevention.”

Some of the consequences of these shifts may not be apparent yet due to short-term federal funding initiatives (e.g., the State Opioid Response grant program) that have temporarily compensated for state cuts. However, these short-term solutions require reauthorization and are vulnerable to the “fiscal cliffs” that occur when federal funds dry up.

Emergency COVID-19 relief efforts may have helped state-level programs stay afloat while masking the full impact of the state cuts. Emerging research has shown that substance use disorders – along with mental/physical health, academic progress, social isolation and many other areas – have likely worsened as a result of the pandemic, making treatment/prevention programs even more essential.

Many of these challenges stem from specific requirements embedded within various policies. Therefore, solutions must involve legislation.

The authors propose that all states attain a minimum standard of funding required to meet local needs for the treatment and prevention of substance use disorder. They must also shift funds to Medicaid to retain adequate, flexible funds for system-level coordination, surveillance and regulation.

“Because Single State Agencies cannot be financed with funds restricted for the reimbursement of patient care, Medicaid cannot act as a substitute for state funds for these agencies,” Andrews says. “We need to clarify – and perhaps redefine – what these agencies’ roles and responsibilities are in the post-Medicaid expansion area and what resources are necessary to carry out these roles effectively.”